Sarah Anne Johnson

It is a multiple million eyed

monster

It is hidden in all its elephants

and selves

–Allen Ginsberg on lysergic acid

In the months of March, April and May of 2016, Toronto was lucky to have three powerful exhibitions by Sarah Anne Johnson. As diverse as these shows were, they converged on the theme of psychedelic drugs, exploring both the destructive and transcendental side of these enigmatic substances.

Over the course of many summers, Johnson attended outdoor music festivals, the likes of The Field and Shambhala on the West Coast, the Winnipeg Folk Fest and Burning Man in the desert of Nevada. At these festivals people park their cars, pitch tents, and wander around in fantastical costumes amid a maze of performing musicians, DJs, and hundreds of other people. Psychedelics course through their veins. They dance to drumbeats conjuring divine encounters, touching mystical states of consciousness.

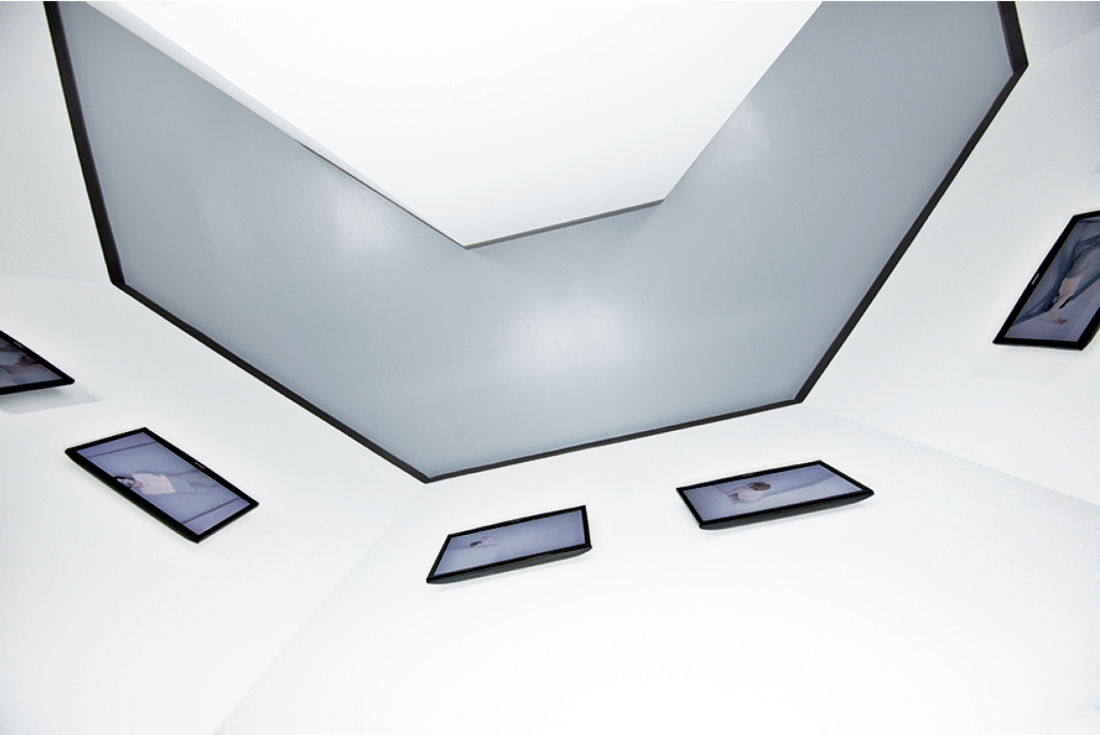

Installation view, Sarah Anne Johnson, Hospital Hallway, 2016, Division Gallery, Toronto. Photograph: Division Gallery.

For Johnson’s maternal grandmother, a very different drug experience took place, an event that would send tremors through the family into future generations. Velma Orlikow checked in to the Allan Memorial Institute in Montreal in 1956, seeking help for post-partum depression, and unknowingly became a test subject for MK-Ultra, a secret CIA research program. The CIA was interested in scientific reports stating that LSD could alter normal behaviour patterns and perhaps open the door to reprogramming, or brainwashing. The drug was seen as a potential tool for turning Soviet spies into allies. The method for achieving this was to find the subject’s weakest point and press on it until that person broke down and became susceptible to complete change.

It was Doctor Ewen Cameron at Allan Memorial who received financial backing from the CIA to test his experimental mind control on dozens of patients, including Orlikow. The treatment involved “sleep therapy,” in which individuals were asleep for months at a time, “depatterning,” which required electroshock and many doses of LSD, and “psychic driving,” which involved heavy sedation and special rooms in which patients were played repeating messages from speakers hidden in their pillows. “Some heard the same message a quarter of a million times,” state Martin Lee and Bruce Shlain, the authors of Acid Dreams The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, The Sixties, and Beyond. Once the “treatment” was over Velma Orlikow was never the same. Deeply traumatized, she became unable to do the things she loved. She could no longer read a whole book, she developed a fear of crowds, suffered from irritability and had difficulty executing domestic tasks, such as cooking meals for her family.

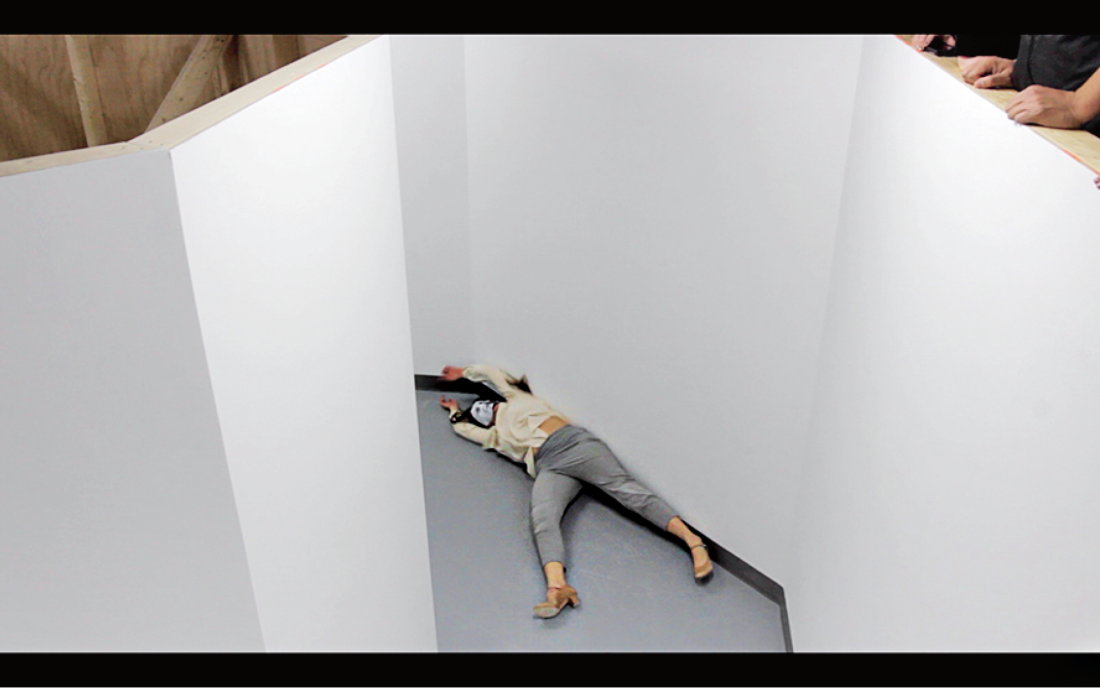

Sarah Anne Johnson, Hospital Hallway, 2016, performance at Division Gallery, Toronto. Photograph: Daniel Goodbaum. © Akimbo Art Promotions.

Over the past 10 years, Johnson has made several bodies of work in response to her grandmother’s experience. In “Hospital Hallway” at Division Gallery, Johnson acts out what a patient at Allan Memorial might have experienced. It is a twofold exhibition: a constructed hallway containing video works, which then doubled as a performance stage for three consecutive nights. Being inside the structure feels like being thrust into one of Jorge Borges’s bizarre worlds. The installation was composed of an octagonal room with an empty corridor in the centre and an elevated viewing platform around its outer circumference. A single door in the framed structure opens into a brightly lit sterile hallway with a grey floor.

Each wall contains a single flatscreen monitor in which Johnson appears in a mask printed with an image of her grandmother’s face. Wearing an ivory ’50s style muslin top and grey pants, she appears drugged, slithering on the floor, banging on the walls of an enclosed sanatorium. In one video loop, she is lying on her stomach, arms gone limp as she slides forward like a lethargic caterpillar. In another, she has used the wall to leverage her legs and torso vertically in a candlestick pose, and proceeds to shake in spasms as though she’s receiving electric shocks. In 15 screens, the variety of her movements is impressive, and with each video in a loop the agony and discomfort is constant, endless.

The Kitchen, 2016, Gallery 44, Toronto. Photograph: Toni Hafkenscheid. Courtesy Gallery 44.

During the live performance, the monitors are gone and viewers climb the staircase on the interior of the octagonal structure and gather on the outer platform to look down. What she did in the videos is now fully sensory. We hear the clattering of her shoes on the walls and her heavy breathing. We hear the sound of hands on the floor, of clothing scratching against the floor. The breathing becomes heavier with exertion as she pushes off the walls, then adheres to them, but it’s impossible to escape—the hallway is a circle. There is no way out, yet she tries, clutches her masked face as she flips and flops, her body flaccid then active, twirling around in manic yet determined circles. She falls flat, adjusts her hair, stands up, tucks in her blouse, and walks backwards to resume her slithering. She pushes herself forward, the grey floor and her grey pants fusing together, the only sound that heavy breathing, then clambering, clutching, pushing, gripping, navigating around the awkward shapes, head on the ground, tapping on the walls checking for some unknown thing, throwing her head back, walking backwards, falling over and beginning to spin around again like a cooped-up animal. I started to worry.

In “The Kitchen” at Gallery 44, Johnson dramatizes her grandmother’s difficulty in doing simple things after Dr. Cameron’s horrific “treatment.” We see her on multiple screens performing tasks in a 1960s kitchen, with her back to the table or kitchen sink and her arms working blindly behind her. She wears a mask of a woman’s face on the back of her head and a wig over her face, so that the resulting effect is a disturbing female figure that looks at first glance as though her arms are attached the wrong way. The simplest tasks are very nearly impossible. We see Johnson peeling a bowl of hard-boiled eggs, decorating a cake with icing, washing a load of dishes, making pasta and meatballs, chopping a salad, and making a peanut butter sandwich. She grows frustrated if a task goes wrong and bursts out in anger—throwing food on the floor, stomping on meatballs in her white heels, or ripping up the botched sandwich, groaning and grunting in frustration. After her angry outbursts, she attempts to calm down and clean up the messes she has made.

Video still, The Kitchen, 2016, Gallery 44, Toronto. Courtesy Gallery 44.

The moments in which she is using a knife are the most cringe inducing. We worry about her fingers—her thumb has a visible cut that is bleeding already. She works to compose herself, keeps cutting, but cuts into her finger. The difficulty of doing all of this with her back to the cutting board is hard to watch, as we bear witness to an individual intensely struggling. It is a deeply heartbreaking picture of women in the domestic realm, struggling, fighting to stay calm, to complete this peanut butter sandwich, to wash that plate. The viewer feels her pain—we wish we could turn her around and make everything easier, but we can’t, and the videos keep playing. All the viewer can do is leave the room.

It is reported that some CIA employees, inmates and psychiatric patients who were given LSD without warning or consent became permanently unwell, while patients in other contexts reported blissfully seeing the secrets of the universe. If given or taken in a supportive environment, psychedelics can be transformational and even therapeutic. Since LSD, or lysergic acid diethylamide, was synthesized from a rye fungus by Swiss chemist Dr. Albert Hofmann in 1938, it has played both the role of covert weapon and beacon for counterculture. Giants of the Beat Generation, like Allen Ginsburg and William S Burroughs, famously experimented with psychedelics and sang their praises as portals into a more forgiving, peaceful new world. But as much as drugs played a role in cultural change, they also opened pathways to various forms of self-indulgent escapism.

Sarah Anne Johnson, Three Wise Guys, 2015, chromogenic print, oil paint, 45 x 55 inches. Courtesy McMichael Canadian Art Collection and Julie Saul Gallery, New York.

In Johnson’s exhibition “Field Trip” at the McMichael, we see the double-edged sword that is psychedelics. With her camera Johnson captures festival revellers in spiritual ecstasy and brain-numbing lethargy. Dozens of photographs are accompanied by three life-size sculptures. But the pictures are far from “straight” photographs; each image has been scratched, cut into, besparkled, or altered in Photoshop. Johnson states that she wants to “show what something looks like, but also what it feels like—to show the surface but also reveal the interior.” A picture alone can show what being high looks like, but not what it feels like.

Fashion at these festivals bends toward spectacle: velvety cowboy hats and feathered boas, tie-dye and tutus, space boots and full-body animal costumes. Some photographs show people with their hands up in the air, feeling one with the universe and each other. But a good trip can quickly turn bad. Johnson has drawn crude happy faces on the people, in oil paint, melting their expressions. She has given some of them cartoon noses, all too big or too small.

The photograph Stay Safe, 2015, depicts a dry-erase board at a festival, listing all the drugs to stay away from—what someone claims to be MDMA is really Methylone, and another mislabelled pill tests to be Ketamine. The Lightshow, 2016, is a life-size sculpture of a partygoer with glow sticks lodged into her entire face, flashing incessantly green, blue, yellow and pink. Her hands drip with sparkle gel that also pours down her chest from the glow stick arrows, as though her blood is, in fact, sparkle juice. These pieces reveal an almost maniacal, brain-dead and definitely disturbing side of the party. There is no consciousness-raising here, only a tired, fried person, over-partied, over-indulged, oversaturated, corroded by a wave of experience that’s too loud, too bright, too long burning.

In his introduction to Acid Dreams, Andrei Codrescu points to the irony in the history of LSD: “The drug that connected so many of us to the organic mystery of a vastly alive universe, turns out to have been at least in the beginning, a secret CIA project to find a truth serum.” The myth and fallout of psychedelics is reflected exactly in Sarah Anne Johnson’s own history and in these intertwined, emotionally moving exhibitions. From Velma Orlikow’s tragic experience at Allan Memorial to 1960s counterculture and its vestiges in modern day festivals, it’s clear that the utopian and dystopian are separated only by a thin and permeable veil. ❚

“Hospital Hallway” was exhibited at Division Gallery, Toronto, from March 19 to April 16, 2016. “Field Trip” was exhibited at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, ON, from March 4 to June 4, 2016. “The Kitchen” was exhibited at G44 Centre for Contemporary Photography, Toronto, from April 1 to April 23, 2016.

Anna Kovler is an artist and writer living in Toronto.