Sakahàn, International Indigineous Art

“Sakahàn, International Indigenous Art” is the first in what is planned to be a quinquennial exhibition devoted to contemporary art by indigenous artists from around the globe. Its title is an Algonquin word that means “to light a fire,” marking an auspicious beginning to an admirable and ambitious project undertaken by the National Gallery of Canada, which resides in traditional Algonquin territory. The largest ever exhibition of contemporary indigenous art, it is also the largest art show the gallery has done, period. Featuring over 150 works by 80 artists from 16 countries, with events and exhibitions coordinated with multiple partnering institutions, the exhibition is so sprawling that the handy and much needed map given to visitors cannot even include all the territory it covers. The exhibition confirms and amplifies the institution’s commitment to the collection, study and exhibition of indigenous art.

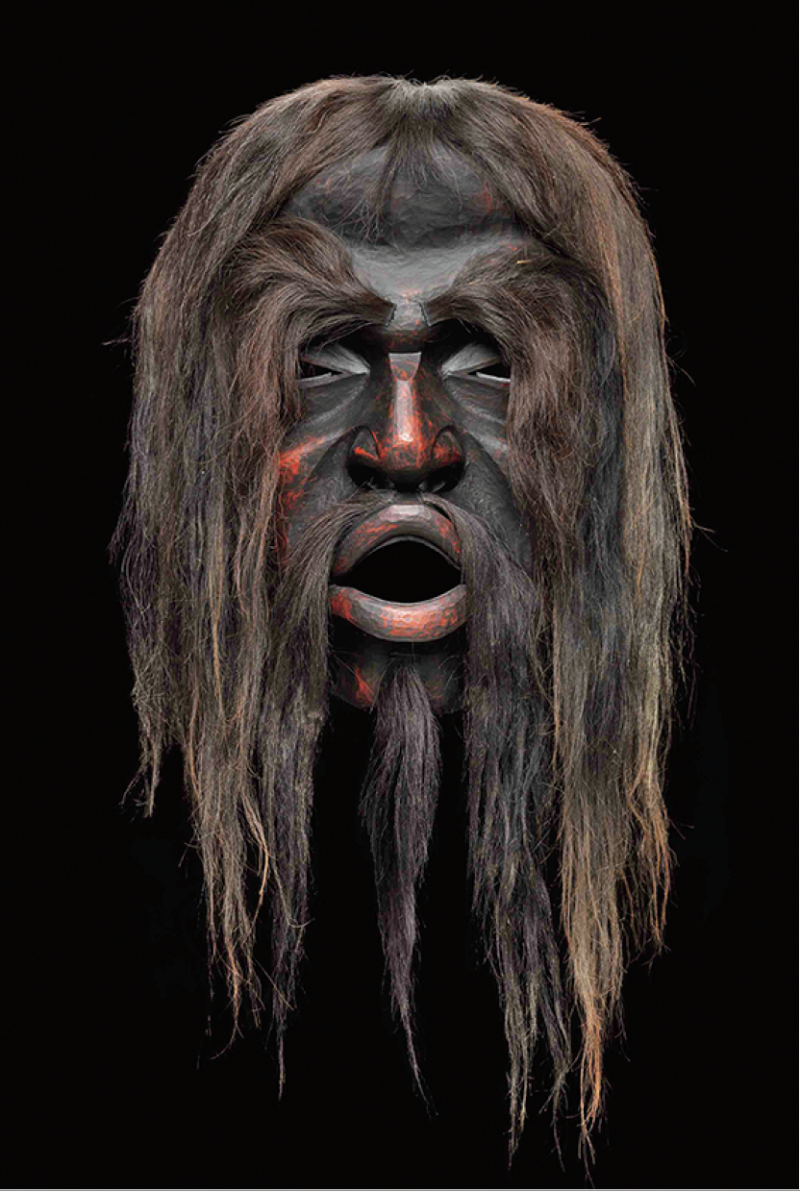

Beau Dick, Tsonokwa Mask, 2007, red cedar, horse hair and acrylic. Collection of Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa. Photograph: Trevor Mills, Vancouver Art Gallery.

Curated by Greg Hill, Candice Hopkins and Christine Lalonde, in consultation with an international team of curatorial advisors and with a video program assembled by Linda Grussani, the exhibition does not offer a narrow viewpoint on the selected works but rather, attempts to be as broad as possible in its scope. In her catalogue essay, Christine Lalonde delineates the three concerns of the curatorial team: that the exhibition would employ an expansive meaning of the term “indigenous,” that it would be set within a global framework that broadened geographic lines entrenched by previous exhibitions, and that it would demonstrate above all that today’s indigenous artists on their own terms are among the leading contemporary artists in the world.

Though it is never explicitly stated as such, the concept of survivance, a neologism coined by the Anishinaabe writer and critic Gerald Vizenor, is consonant with much of the work in the exhibition and with the curatorial strategies of the exhibition itself. Cited in the catalogue, Vizenor also contributes the essay “Native Cosmototemic Art,” another occasion in which he articulates the meaning of the word that combines survival with resistance. Survivance connotes an active sense of the presence of indigenous peoples in their contemporary actuality as opposed to a romanticized and stereotypical understanding of them as belonging to the past. “Sakahàn” has certainly created an active sense of presence for contemporary indigenous art in Ottawa and exploded many conceptions of what it might be. With much fanfare leading up to the show, several blockbuster works have been highly publicized with attention- grabbing phrases like “a plane crushed by a rock!” in the case of Cherokee artist Jimmie Durham’s astounding 2008 piece, Encore tranquilité, purchased by the gallery in 2011, or “underwater without getting wet,” describing the impressive and quite literally immersive video installation Aniwaniwa, 2007, by the Maˉori artists Brett Graham and Rachael Rakena. However, the curators achieve this sense of presence and resistance at various scales and registers, not just the blockbuster, throughout the exhibition.

Marie Watt, Three Sisters: Cousin Rose, Sky Woman, Four Pelts and All My Relations (detail), 2007, wool blankets, satin binding, thread, salvaged industrial yellow cedar timber base. Collection of Seattle Art Museum, Seattle Washington. Courtesy the artist.

Woven through all the areas allotted for special exhibitions and into the contemporary art area of the permanent collection, the connections between works are not pronounced, leaving attentive viewers to pick up the created threads of dialogue. One thoughtful juxtaposition places dark string, 2010, by Kanien’kehá:ka artist Greg Staats next to Métis artist Edward Poitras’s 2000 Pounds of Rope, 2004. Staats brings a small purple wampum string to ethereal life by placing it within a real-time video feedback loop, while Poitras renders with exacting weight a claim made by historical re- enactors about the length of rope sold to commemorate the hanging of Louis Riel. Works like these in accumulative combination elicit powerful visceral responses.

In another gallery, Anishinaabe artist Rebecca Belmore’s Fringe, 2008, a life-size back-lit photograph of a woman with an enormous wound across her back, stitched together and beaded to appear as if flowing with blood, is flanked by Kikuyu artist Wangechi Mutu’s Sleeping Heads, 2006, a series of recumbent heads collaged with body parts culled from magazines. Mutu’s installation literally inflicts garish wounds in the wall on which her collages are displayed. On the remaining walls, several drawings and paintings by the Gond artist Venkat Raman Singh Shyam depict, in a kind of folk-documentary style, recent violent events such as a terrorist attack in Mumbai. The energy from these works courses through a sculpture on a low plinth positioned in the centre of the room: Alàs (Naked), 2002, by Sámi artist Ingunn Utsi. A strange assemblage of rabbit skin, barbed wire, and natural growth on birch, Alàs attains an auratic charge in this room where the dynamic tension of attraction and repulsion is at its strongest—perhaps the primal scene of this exhibition which bears witness to trauma and resilience in striking ways.

The exhibition has a presence outside of the conventional gallery spaces as well. Several site-specific works created for the exhibition have been inventively installed in surprising places throughout the building. Some are hard to miss. A giant banner generated from Earth and Sky, a 2008 drawing of the Arctic landscape and the cosmos that was created in a collaboration between the Inuit artist Shuvinai Ashoona and the Dutch and Canadian artist John Noestheden, runs for over 50 metres along the length of the grand ramp leading into the exhibition spaces. Celebrating Mohawk construction workers’ contributions to the Manhattan skyline, among other things, Seneca artist Marie Watt’s Blanket Stories: Seven Generations, Adawe, and Hearth is a stack of donated blankets that towers up to a vertiginous height in an open skylight area, traversing and observable from the two levels of the building. The Algonquin artist Nadia Myre’s piece, For those who cannot speak: the land, the water, the animals and the future generations, is a digital print of rows of wampum beads that expresses solidarity with a declaration made on January 11, 2013 by a group of Algonquin kokoms (grandmothers) on Parliament Hill. Though it too is printed at a great scale, over 57 metres, I almost didn’t see it, as it is adhered to and completely covers an interior window, becoming an aspect of the architecture. Another stealthy insertion can be discovered in the gift shop: posters from Greenlandic artist Julie Edel Hardenberg’s 2011 series “Sapiitsut/ Heroes” are almost hidden in plain sight. Advertising fictional movies like The Decolonized or Sangatak – Nothing Will Stop Her that feature ethnic Greenlandic people in typical Hollywood scenarios, the posters are for sale. Displayed with pedagogical material, they continue the exhibition in an unexpected but fitting place.

“Sakahàn” also has a strong presence outside the gallery walls. Hardenberg’s posters can be additionally seen pasted across construction hoarding on Sparks Street. Blackfoot artist Terrance Houle and Onondaga artist Jeff Thomas have work publicly installed in the ByWard Market. A rock carving by Tlingit and Aleut artist Nicholas Galanin, commissioned for the exhibition, is on the rocky outcropping behind the Gallery near Nepean Point. Entitled Nature Will Reclaim You, it features floral patterns taken from period wallpaper, and it will likely remain for centuries to come.

Rebecca Belmore, Fringe, 2008, Cibachrome transparency in fluorescent light box. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased 2011. Photograph: © NGC.

Exterior works have also animated the grounds of the National Gallery as never before, increasing engagement with its picturesque setting. Certainly the most spectacular work is Iluliaq (Iceberg), 2013, by Greenlandic artist Inuk Silis Høegh. Conveniently covering scaffolding during a renovation, a massive inkjet print on scrim mesh made the building’s Great Hall outwardly appear to be an iceberg that had drifted up the Ottawa River. In vivid contrast to its surroundings, it was visible from kilometres away, making “Sakahàn” a truly landmark exhibition. Approaching it through the grounds landscaped to suggest the terrain of the Canadian North, you can hear the sounds of ice groaning and melting, an audio element that underscores current precarity. A much smaller gesture entitled Secret Hidden Garden proves to be equally effective. Installed in the gallery’s sunken garden by Sámi artist Geir Tore Holm, it is a sleek minimalist planter that has been created to cultivate numerous indigenous medicinal plants. Most saliently, the plants will be harvested and received by Ottawa’s recently opened Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health, manifesting in a concrete way the transmission of knowledge and engagement that will come from this exhibition.

The space allotted for this review can only contain a cursory account of “Sakahàn’s” accomplishments. Of at least 15 other exhibitions and events organized in partnership with the National Gallery, I will mention only one: the excellent collection of zines, mixtapes of Greenlandic rap music, sculptures, photographs and videos at SAW Gallery that spanned the career of Joar Nango, a Sámi artist and architect. Nango’s work provides an introduction to another concept, indigenuity, which is local and indigenous ingenuity in everyday design manifested in ad-hoc constructions that are sensitive to their environment. With the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as another touchstone text, the forward thinking on display in “Sakahàn” provides multiple tools for a general audience to think critically about the issues presented.

“Sakahàn, International Indigenous Art” was exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, from May 17 to September 2, 2013.

Michael Davidge is an artist, writer and independent curator who lives in Ottawa.