Roy Arden

Every city has a particular face it puts on for tourist brochures. Vancouver, especially, does it well. Bookended by Expo ’86 and the upcoming Winter Olympics in 2010, it’s a city that trades on lifestyle promises and its “Supernatural(™)” surroundings. Despite a certain myopia—or some have said amnesia—in dealing with the darker corners of its own history and current social problems, its urban clear-cut template provides plenty of material for local artists to work with.

Of all the disciples of the influential “Vancouver School,” I find Roy Arden’s work the most interesting: he’s thoroughly engaged with the photographic image on an art-historical and theoretical level, not only as an artist but as a teacher and curator. Unlike some of his contemporaries, the image is rarely trumped by the theory. That’s not to say that he’s a 100% straight shooter, either, as his works employ a quasi-Masonic strategy, particular to contemporary art, of showing what is hidden in plain view. His signature large-format photographs of BC’s economic life— monster houses, pulp mill dumps and sculptural arrangements of plastic chairs on shipping pallet/ podiums at Wal-Mart—appear via the camera’s presumably objective gaze, masquerading at points as reportage. If you bear in mind the intertwined environmental, industrial, socio-economic and political aspects of British Columbia’s landscape, you can blink and see what curator Dieter Roelstraete called “Lotusland’s dystopian other”: the mountains are hypnotic, but ultimately act as venue for industry. Shipping, real estate, land development and tourism have all been grafted onto nature, acting as a pretty backdrop—and distraction— for numerous social ills.

Roy Arden, Development, 1993, chromogenic print. Collection of Family Von Brauckmann. Courtesy the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Sandwiched between Georgia O’Keeffe drawing crowds on the main floor and the sepulchral Emily Carr permanent exhibit up top, the exhibition, “Roy Arden,” seems well aware of its place within an institution/cultural destination that relies on bread-and-butter exhibits to attract those who maybe weren’t coming to see some heavy photo-conceptualism. As a midcareer retrospective, it’s the arrangement of the exhibition that allows Arden’s work to hum. Instead of the usual chronological display, there is an interesting “compare and contrast” strategy at hand, each piece, or grouping of works from different periods, enacting a form of dialogue with each other and, more importantly, with the viewer. In a public museum setting, the absence of a linear biographical arc is particularly refreshing; a different kind of circuitry.

Of particular note, as well, is the “Artist’s Choice” exhibit one floor below, where Arden was allowed to run riot through the VAG’s archives. It’s an impressive exhibit that merits a larger word count than I have, but this I can say: all the heavy hitters are there. Muybridge, the Bechers, Winogrand, Abbott, Wallace and Wall represent the photographic tradition alongside Goya, EJ Hughes, Rauschenberg and Beuys. Grouped into a number of themes, the exhibit not only works to illustrate the history of photography’s aesthetic and theoretical shifts and reveal the connections among other media, but acts as an autobiographical tool: here, Arden is plainly forthcoming about his influences. Ed Ruscha and Hans-Peter Feldmann, for instance, stick out in the realm of the taxonomical, hired-out or appropriated image—key photo-conceptual strategies—while Thomas Struth’s monumental prints of industry offer an aesthetic and conceptual gateway to Arden’s work upstairs.

Roy Arden, Discarded Chairs (#1), Geneva, 1981–1985, cibachrome print. Courtesy the artist and Monte Clark Gallery, Vancouver.

Upstairs, as well as downstairs, the representational trickery of the photograph, and the interrogation thereof, is put to full use: a soil compactor in the foreground of a new housing development oscillates between being a caustic critique of (post-) colonial development, while looking like a promotional image for a landscaping company. Pictures of totem poles at the Arthur Erickson-designed Museum of Anthropology at UBC share the same gallery wing with reproduced images of First Nations people performing the Passion Play.

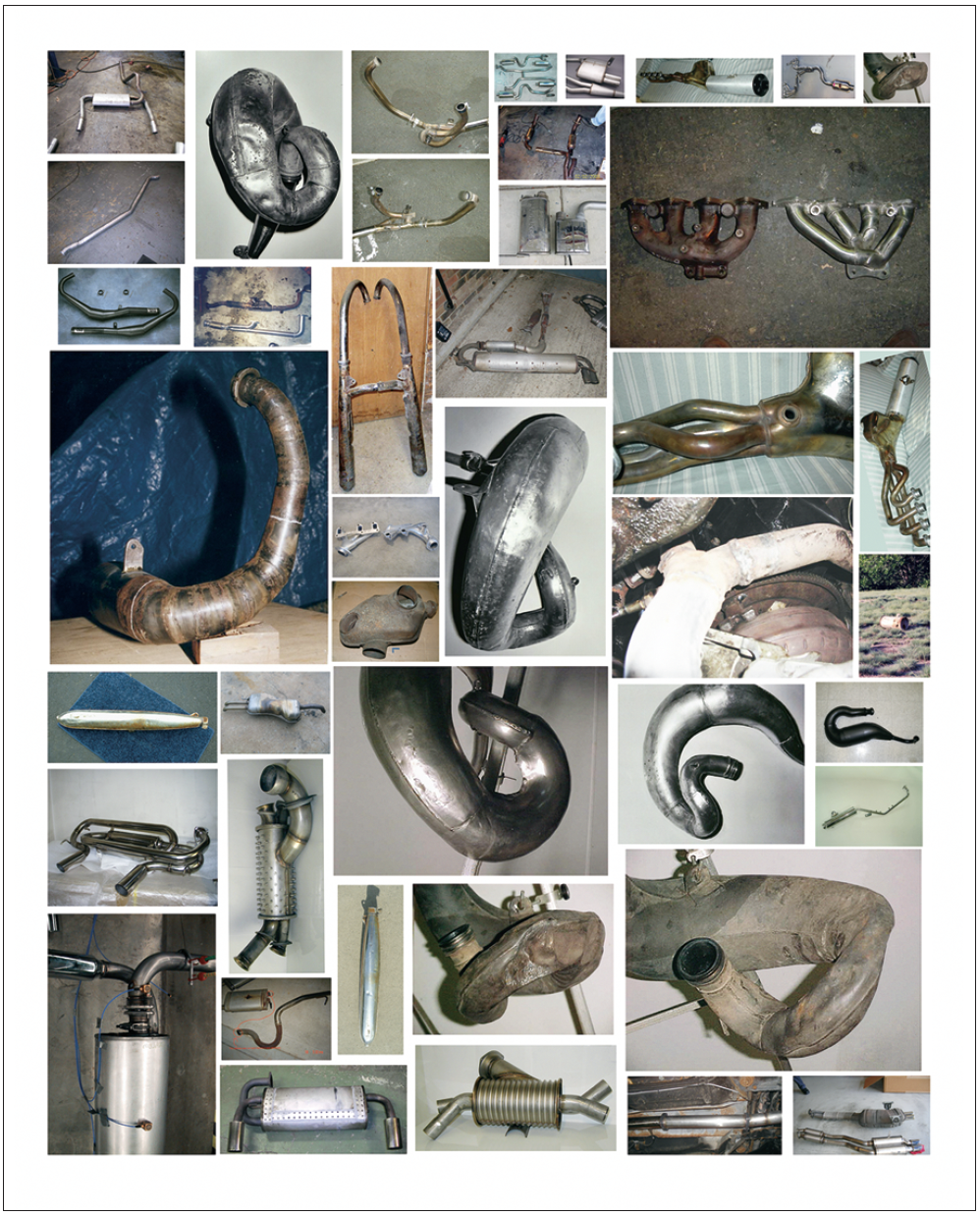

Looking at his mid-’80s works in particular, archival photographs are set as diptychs, paired with plain monochromes, highlighting an aesthetic rupture between image and colour fi eld, spurring either further research or curiosity, by interrogating British Columbia’s history through its representation and construction. Does the relocation of BC’s Nikkei to internment camps or the docking of hopeful Sikh/Indian immigrants or Vancouver’s Bloody Sunday riots of 1938 change as events, once canonized, and now aestheticized? The power of the photographic image becomes upended. What impact do any of his images have, as art, as protest, as documentation, as part of the local history, and, importantly, what power do they wield in terms of value now, as part of the local and global art economy? Looking at his archive of 28,000 JPEGs pulled from the Interweb in the slide show, The World as Will and Representation—Archive 2007 (viewable at <royarden.com>), further questions arise. What weight does the photographic image itself have, now that it has been disembodied and released into the realm of pixels, information, data? Similar to Gerhard Richter’s ongoing Atlas project, at least Richter’s scrapbooks have physical clippings bound to the pages.

Roy Arden, Basic Anatomy, 2007, archival pigment print. Courtesy the artist and Monte Clark Gallery, Vancouver.

Arden’s recent video works, while shaky at times, act as an extension of previous themes. Supernatural (the title is a play on one of BC’s many marketing hooks) stands out as a powerful installation showing footage from Stanley Cup riots just a brick’s throw away on Granville Street in 1994. Watching the short vignettes, their reading constantly shifts between horror at the injured, disdain for the yahoos destroying property and anger at the riot cops who seem to carry a sense of “Yeehaw, this is what I signed up for.” As the video unfolds, the realization dawns that we’re seeing two groups of people—one not intent on any WTO/“Battle of Seattle”- style heroics and the other police just doing their jobs by trying to restore order. The images continue to push and pull, though, eventually combining to show two camps at deep odds coming to rest as a darkly sardonic work threading back to Arden’s historical diptychs of the 1938 riots, or images of the aforementioned Museum of Anthropology, just a stone’s throw from the RCMP pepper spray incident at UBC. All the while, they recall other social ruptures, from the 1907 anti-Asian riots to 2002’s Guns ’N Roses fan riot where the police posted footage on the Internet so citizens could rat out “persons of interest.” Photographs—and now the video image—can act as evidence, and when I go back through the exhibit after watching this particular piece, the meaning of his work shifts once again; more damning, revealing implication, and even complicity—culturally, politically and otherwise. Welcome to, as the licence plates now say, “The Best Place on Earth.”

Roy Arden, D’Elegance (#1), 2000, gelatin silver print. Courtesy the artist and Monte Clark Gallery, Vancouver.

It’s these questions and cross-connections that consistently emerge as you move through the gallery space. As a medium that records information, the photograph depends on spin, and, as far as most photo-conceptual practice in Vancouver is concerned, the spin is how opaque and academic can the references be while appearing “straight.” So is it necessary to think three steps ahead of the image, like in a chess match? And after seeing and studying enough of Vancouver School work, would you even want to? The jargon, to be sure, is there in Roy Arden’s pictures, but only for those who care to dig it out: to borrow from Charles Jencks and postmodern architecture, Arden’s work is “double-coded,” in that it can address and be read by more than one audience. Photographs are generally loaded with numerous considerations, but Arden’s work, albeit didactic at points, doesn’t pander to the general viewing public, nor to the academically inclined. The surface of his prints asks to be scratched, but doesn’t carry the “wink-wink” air of being exclusive parlour games for those versed in the discourse. Instead of being wilfully obscure, Arden’s work allows for plural readings, and is, in turn, democratic. Or so it appears. ■

“Roy Arden” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from October 20, 2007, to January 20, 2008.

Christopher Olson is a student in Vancouver and frequent contributor to Border Crossings, Vancouver Review and Front magazines.