Ron Shuebrook

Ingres called drawing “the probity of art.” To Ron Shuebrook, whose drawing survey is currently on a cross-Canada tour, probity—integrity, seriousness—is fundamental. Shuebrook, now 70, is best known as an abstract painter whose lengthy, rigorous practice is grounded in the formalist aesthetics of late Modernism. When his survey exhibition was presented in Halifax at MSVU Art Gallery, the respected artist and educator gave a talk, surrounded by works that initially seem to hold fast to the Greenbergian tenet that painting (or, in this case, drawing) should refer to nothing outside itself and its own material processes. But Shuebrook began his artist’s talk with the disarmingly heretical assertion that “there is always a social dimension to these works.” Therein lies much of the fascination of this particular selection.

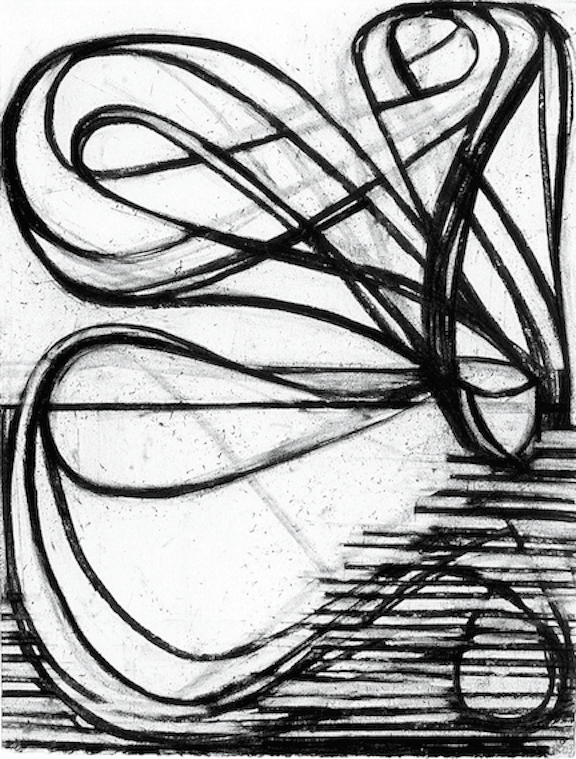

Guest Curator John Kissick chose 23 of Shuebrook’s compressed charcoal drawings that together problematize any easy reading of Shuebrook’s Modernism. Not that the formalist ancestry isn’t clear. “I don’t want to hide my tracks at all,” says Shuebrook. From the emphatic geometry of straight lines, controlled curves and small punctuating squares in his Untitled, 1994, through the zooming arabesques and subtle erasures of Provincetown Monkeyrope (for Albert Pinkham Ryder), 2000, to the compendium of personal motifs dancing in the structurally ambitious Secrets and Revelations, 2013, Shuebrook acknowledges the legacies of Mondrian, Matisse and Motherwell. These works exemplify what Kissick calls Shuebrook’s “dogged commitment to things; to ideas and values, and…to the notion that just because something is no longer critically or aesthetically fashionable doesn’t mean it isn’t still meaningful or worth fighting for.”

Ron Shuebrook, Provincetown Monkeyrope, 2003, charcoal on rag paper, 65.5 x 49.5 cm. Courtesy the artist.

Shuebrook’s improvisatory approach—the point-counterpoint of gesture and erasure—seldom allows these works to congeal into orthodoxy. What most intrigues, however, is not their hard-won authoritative elegance but the accumulated evidence of doubt: the increasing openness to potentially disruptive pictorial elements. This aesthetic antinomy is most present in the oversize drawing Wharf, 2013, and the curious “Radiance” series.

Wharf is dominated by a large, shed-like form in rich velvety-black charcoal, intersected by lines suggesting derricks, ladders and dock litter, and punctuated by abstract markings. Shuebrook admits to being ill at ease with figurative references (some, like the derrick, explicitly representational) but he does not shy away from explaining their connection to personal history. Wharf is distilled from his experience of three significant places: the Aspotogan Peninsula in Nova Scotia, where his studio stands only metres from the harbour; Provincetown, Massachussetts, where, on a fellowship in 1969–70, he got to know the legendary Robert Motherwell, as well as Myron Stout and Fritz Bultman; and the Chatham region of southwest Ontario, where he was recently artist-in-residence at the refurbished Thames Art Gallery—the gallery that initiated the current exhibition.

Such personally significant experiences suggest to Shuebrook a causality—action and reaction—that parallels the aesthetic processes manifest in the drawings. It asserts the importance of place and time, of being located within specific social histories and aesthetic genealogies of reference. He talks about wanting to know the specificity of the local, how it becomes what it is (much like how a drawing becomes what it is). This concern with the local has motivated him to write about artists connected to the communities in which he has actually lived: Canning, Nova Scotia; the Aspotogan Peninsula; Guelph, Ontario.

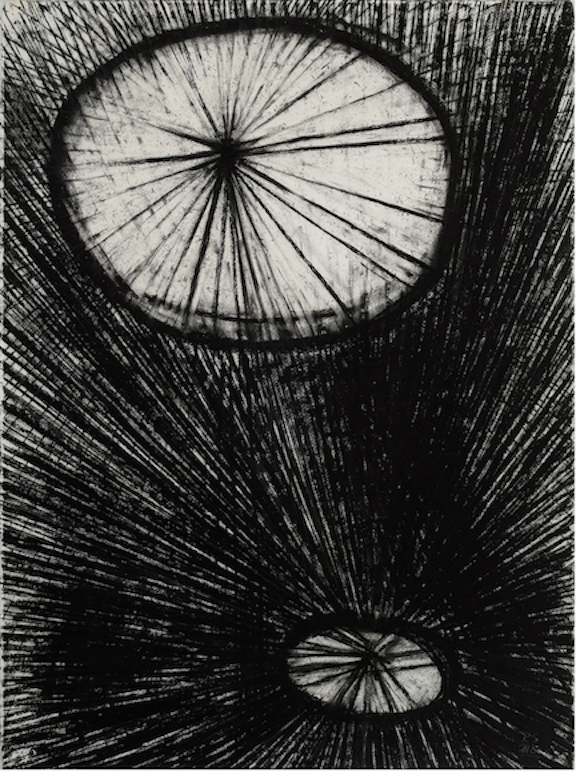

Radiance Series (Two Discs), 2011, charcoal on rag paper, 76 x 57 cm. Courtesy the artist.

The “Radiance” series is a risky, seemingly expressionistic set of drawings in which linearly constructed fans, folds and vectors suggest warped space-time, the gravitational pull of stars and galaxies and dark matter. On the one hand, according to Shuebrook, these drawings are simply an accumulation of linear elements that become a field, elements that he first observed scratched into the small vessels of Austrian-British potter Lucie Rie, to describe volumes. His comment acknowledges the practicalities of working with “a certain material” (about as Greenbergian as one can get). But he goes on to say that they are also about depicted light—an emotional experience of observation in the world at a certain time, which he feels links him to Whistler, Goya and “a sense of darkness.” Dark Radiance, 2013, and similar images, were stimulated by specific experiences and memories—among the more indelible, the horror of the Kent State shootings, 1970, that Shuebrook witnessed first-hand, provoking a moral repugnance that led him to reject the US and move to Canada. These may be abstract images, but they are loaded with personal existential and metaphoric content.

This exhibition presents Shuebrook’s drawings not only as works of art complete in themselves, but also as instances from a lifetime of exploration, of questioning the nature of the perceptual object, how it finds its place in the visual world and simultaneously in the social world. His willingness to test his own hard-won position has very little to do with trendy theorizing and everything to do with probity. He asks the difficult questions—the ones that, in this era of aesthetic relativism and unparalleled cynicism, are often downplayed in favour of more immediate success. But there is no shortcut to the place he presently holds. ❚

_“Ron Shuebrook: Drawings” was exhibited at MSVU Art Gallery, Halifax, from May 24 to August 10, 2014. It has been exhibited at the Thames Art Gallery, Chatham, ON, and the Macdonald Stuart Art Centre, Guelph, ON, and will be exhibited at the Robert McLaughlin Gallery, Oshawa, ON, from October 11, 2014 to January 25, 2015 and the Kelowna Art Gallery from March 7 to April 26, 2015. _

Susan Gibson Garvey is a visual artist, curator, educator and writer living in Canning, Nova Scotia.