Rodney Graham and Tacita Dean

The lighthouse holds a special place in our collective imagination: as a navigational aid for safe passage, it’s a symbolic reminder that somebody—or some thing—is watching out for us. The job of lighthouse keeper was a dedicated one, with loneliness, danger and tedium as fringe benefits. It was an honourable, soggy job and somebody had to do it, but since the advent of automation in the 1950s, the keeper’s role as nautical steward has all but faded. The Charles H Scott Gallery in Vancouver offered their take on the beacon’s cultural significance: one of Tacita Dean’s sublime signature works playing it straight against Rodney Graham’s entertaining penchant for playing dress-up.

In Lighthouse Keeper with Lighthouse Model, 1955, Graham appears to have lots of time on his hands. In a large back-lit photograph, a lighthouse keeper relaxes in profile, warming his feet on the open door of an old stove, studying a book on—you got it—lighthouses. Behind him, tins full of paintbrushes sit on the kitchen table next to a scale model-in-progress of the iconic Minot’s Ledge lighthouse. A Hawaiian exotica record from the 1950s plays on the phonograph, wool socks hang drying in the background. It looks cozy, if a little lonely. Sentimental, even unsurprisingly, Graham name-checked Norman Rockwell as partial inspiration for the work.

A collection of archival prints and antiques under Plexiglas serve to complement the big image. Amid log books, binoculars, painted driftwood, pictures and a Lothrop’s foghorn sitting silently on a plinth with a do not touch sign, there are stories: the simple, framed photo documentation of a beacon’s spring mechanisms—austere in form and blankly taxonomical, not unlike a work by the Bechers—turns out to be police evidence from the 1928 murder of a lighthouse keeper in FitzHugh Sound, bc. This hangs above a vitrine dedicated to the Stevensons, a family with an established legacy as lighthouse designers and builders. The clan included one Robert Louis, who trained in the craft but gave up the family trade to become a writer and an inspiration to Walter Mitty-like adventurers everywhere.

Tacita Dean, Disappearance at Sea, 1996, still from 16mm anamorphic film. Courtesy the Frith Street Gallery, London.

These curios form a strategic web between object, main image and theme, pointing to history and place, with the exhibit just a stone’s throw away from the docks on Granville Island. Here, the language of the contemporary gallery is folded into the history/heritage museum. While the large photograph acts as a painterly rebus, the objects inside the frame, masquerading as decoration, create a sort of mise en abyme. To wit: Minot’s Ledge is represented on the buttons on his uniform coat draped behind him on a chair. A postcard of the lighthouse in the photograph is found framed on the other side of the gallery, and the image of a kitchen in his book reflects the room he inhabits.

With everything hidden in plain view, these details reveal the tableau as a forced narrative while the image itself, split down the middle into two lightboxes, showcases a certain formal logic and cinematic rigour: his cable-knit sweater and wool pants look like they were just bought off the rack. The painted walls in the cabin are too shiny, too acrylic, the light too garish. In short, what is the constructed set piece, archival imagery and folksy nautical curios asking: is Vancouver’s photographic methodology now simply a trademarked regional idiom, part of history alongside bc’s own coastal and nautical motifs? Looking over his referential practice and the roles he assumes as performer, collector and enthusiast, I would say that the piece is a rich assemblage of footnotes, Graham doing Graham in a fitting environment.

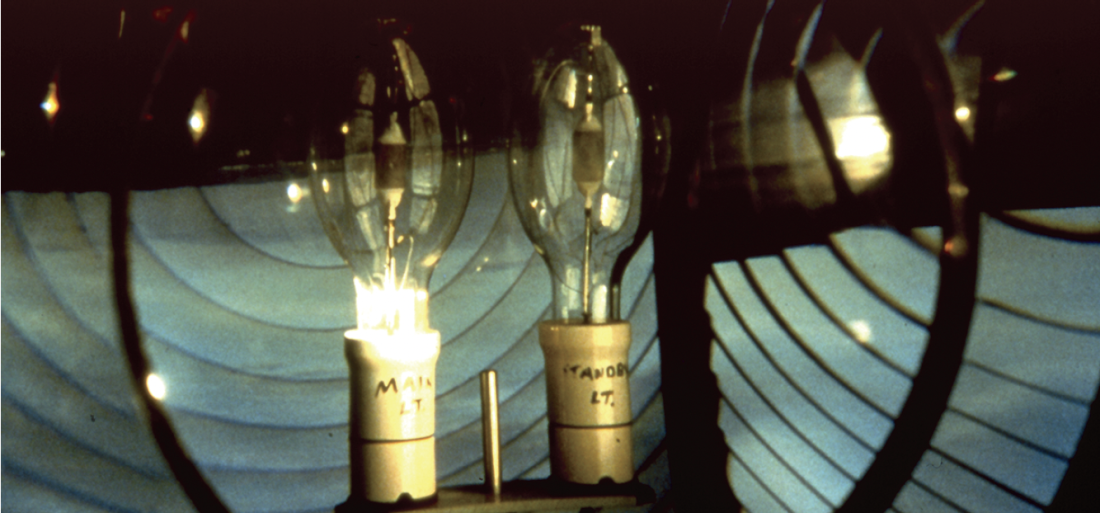

Part of Tacita Dean’s body of work is married to the sea, with pieces like 1999’s Teignmouth Electron and It Is the Mercy, based on Donald Crowhurst’s (and perhaps by extension, Bas Jan Ader’s) story of madness, defeat and surrender to the ocean after a botched attempt at sailing round the world. Here, the lighthouse as symbol of safety working against violent and unforgiving forces stars in Disappearance at Sea. In the documenting of its basic functionality as dusk turns to dark, not much happens other than long takes of a rotating Fresnel lens as it scans the gloaming, but not much else needs to occur.

Rodney Graham, Lighthouse Keeper with Lighthouse Model, 1955, 2010, two painted aluminum lightboxes with transmounted chromogenic transparencies, each panel 112 3/4 x 71 3/4.” Installation view of “The Voyage, or Three Years at Sea.” Photograph: Scott Massey. Courtesy the Charles H Scott Gallery and Vancouver Maritime Museum.

It’s a favourite aesthetic strategy of mine, the long take, with masters ranging from Tarkovsky to Ming-ling Tsai. It can act as a litmus test, where nuance embedded in a perceived non-event becomes the payoff, inviting viewers to settle in, entranced and hyper-aware, or to move on because they’re tired of waiting for “something to happen.”

Over the course of Dean’s 15-minute film loop, the edit itself becomes an event. Like tracing the movement of the minute hand on a clock, day turns to night through jump-cuts between the lens in close-up—creating in-camera flares to the tower against a backdrop of pink sky—ending with a faint sliver of light making its rounds against a craggy rock face. As the screen darkens, so does the installation: the wind roars, waves and seagulls become claustrophobic pink noise. While the clacking film projector leaks strips of prismatic light out its side and onto the ceiling of the space, serving to anchor the viewer in darkness, the silver screen and beam’s beacon fade to black before resuming.

A recurring theme in Dean’s work is her interest in obsolescence: by shooting 16mm film, or as evidenced in 2006’s Kodak, which unobtrusively documents the last rounds of celluloid rolling off of the production line in Chalon-sur-Saône, France, Disappearance at Sea shows the lighthouse stripped of human presence or heroism, automatic like a traffic light. Still, it resonates: after researching the feats of ingenuity and engineering involved in the design and construction of lighthouses, and writing this a week after watching in horror as a tsunami’s landfall consumed whole communities on the northeastern coast of Japan on live tv, I find that the heft of her nautical work reminds us of natural forces, how they dwarf us, and how we negotiate them via our puny contraptions. It’s an elegiac, haunting piece and an endurance run that was a pleasure to experience in person. ❚

“The Voyage, or Three Years at Sea – Part 1” was exhibited at the Charles H Scott Gallery in Vancouver from January 19 to February 20, 2011.

Christopher Olson is a frequent contributor to Border Crossings and Vancouver Review magazine.