Rodney Graham

There are rumblings in the arcades: a gong, actually. Like a persistent ringing in the ear that signals (beautiful?) tumour growth, a dim echo transmits from the far reaches of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montreal, and those fragments wrap a tether around the viewer walking through Rodney Graham’s Montreal exhibition.

I can’t help but think, What’s that damn noise? Familiars of this Vancouverite’s penchant for echoes are most likely utterly amused by this audio component. Before seeing the work emitting the gong, I am only bemused, but it gets better. Unfortunately, before coming across that gem of a work, it gets a lot worse. The climactic moments of Graham’s show first require the viewer to carve through a patchy assortment. There is also white space, a lot of it. Wandering space, passages that give the work room, or just a thin show.

Rodney Graham, How I Became a Ramblin’ Man, 1999. Installation, 35 mm colour film transferred on DVD, continuous loop, 9 min. sound. Production: Donald Young Gallery, Chicago. Photos: Richard-Max Tremblay. All photographs courtesy Montreal Museum of Contemporary Art.

Graham fans will find rally points to celebrate here and he’s celebrated for good reason. There are light boxes and they are glowing, perfectly constructed, crisp, beautiful objects. There are film loops and they are the cyclical catastrophes that are Graham’s hallmark.

A forgettable three-way of crusted and anomalous paintings is followed by a screen door—modelled after one from Elvis Presley’s home and cast in silver, but it simply doesn’t carry the surprise of materiality that it promises. Throwing a delicious pallor over the room is, rather expectedly, a glowing diptych light box from 2005: a photograph of the artist decked out in robes, posing as Erasmus (and perched backwards on his hobby horse) with a (wink) Vancouver phone book in his hands. My precocious companion points out the phone book before a nearby didactic panel has the chance to let the cat out of the bag. A faint smile chugs up from my insides but is immediately stifled by the familiar: “Light boxes—again?” Should/could this format be outlawed, and soon? It seems to have become the perennial medium of some Canadian artists.

Rodney Graham, How I Became a Ramblin’ Man.

Feeling unduly resistant to what this show has to offer, I wander back to the entrance, hoping for a fresh start with a suite of screen-printed bar mirrors. An anomaly between the didactic and a label for the piece leaves me wondering about its title (A Glass of Beer? Or is it The Glass of Beer?). This Warhol’ed silkscreen-Folies Bergere trick leaves my reflection standing behind Graham’s auto-portrait as a buttoned-up Mariachi member. A niggling voice makes me wonder if it isn’t a bit tired to fit so many references into one piece, even if the aim is absurdist.

Awakening gives us more of the heavy metal imagery that now seems de rigeur in contemporary art, in this case as a recreation of a well-known photo of progenitors Black Sabbath. “The band,” played by some phenomenal long-hairs, stands mockingly over a man lying on a park bench (Graham). I can’t help but see an enactment of the patrimony of Vancouver’s golden fleece here, like some self-reflexive prediction for the changing of the guard. Graham’s bench-recumbent body seems on the verge of rising, lumbering, zombie-like, to take Ozzy out. Which is to say: Graham has still got hits in him. There is something satisfying about his ability to take the piss out of himself, but the whole affair seems spoiled and made fussy by a full-sized negative of Awakening hanging en face. Not unlike Sabbath’s miserable 1970 cover of Evil Woman, the copy does not chart.

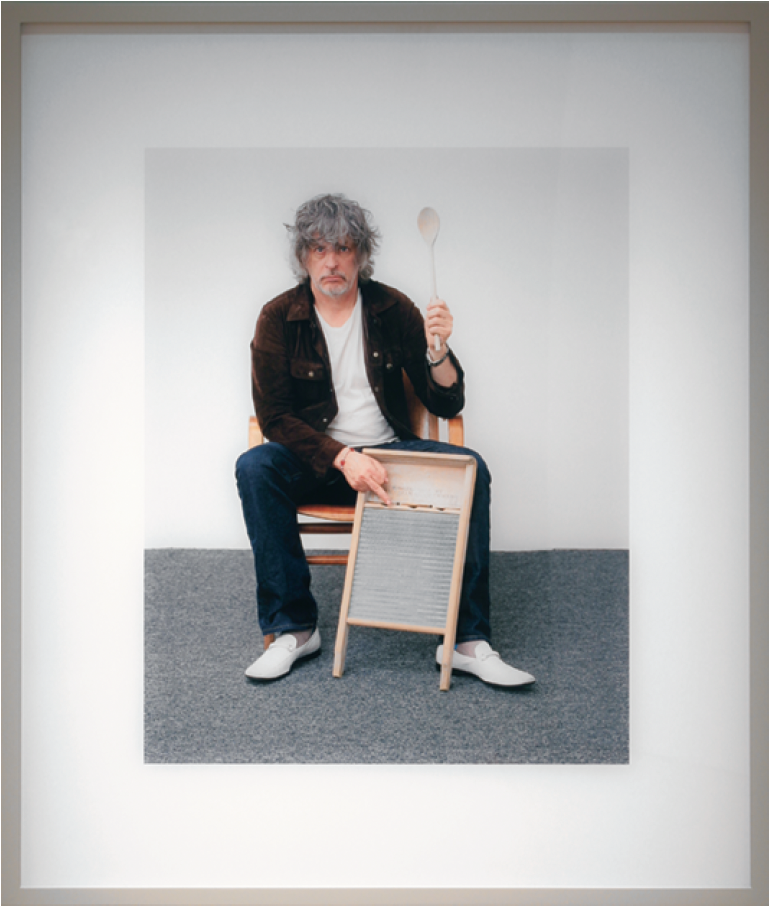

Rodney Graham, Artist in his Studio (Moby Grape), 2006, colour photograph. Production: Donald Young Gallery, Chicago, and Hauser & Wirth, Zurich & London.

How I Became a Ramblin’ Man is the generous offering early in the space. Ramblin’ Man has become Graham’s Greatest Hit. It shows the cyclical narrative of a cowboy—played by the artist yet again—wandering in and out of picturesque, amazingly framed landscapes. He plaintively moans, during a guitar-accompanied interlude, “the city life just got me down.” Flaneur, down on his luck, (prairie) storm and (saddle) stress, a narrative structure that slyly echoes in its back-and-forth, the looping format of the video and our own absurd wanderings through the gallery, through the day. The icing on the icing comes during a shot of a quick chord change, in which I swear I see Graham flash his middle finger at me. I’m delighted for an instant. I do my best not to take it personally but start getting suspicious when the bird makes a second appearance in Artist in his Studio (Moby Grape) on the hand of a washboard player, played by Graham again.

Lobbing Potatoes at a Gong is a determined re-enactment of a sort of Fluxus performance that never happened, at least not in 1969. Graham sits in a slouch before an audience—or is this the readytop position for lobbing potatoes?— gropes for potatoes from a nearby table and tosses them at a gong on the other side of the room. The marvellous thing is how seriously the audience members in the footage are taking it all in, matched only by Graham’s own nuanced pauses. He misses often. However, each time he hits the mark, a glorious resonance erupts from the screening room. The scoring potatoes were distilled into a bottle of Lobbing Potatoes at a Gong Vodka 1969. It’s the perfect amalgam for this exhibition: less than perfect aim here. The great ones should have been distilled, and the rest forgotten. The few focussed ringers left me wishing there had been more. ■

“Rodney Graham” was exhibited at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montreal from October 7, 2006, to January 7, 2007.

Mark Clintberg is an artist, writer and independent curator based in Montreal.