Robert Youds

Robert Youds has used the adjective “handmade” before as one of a number of titling taglines repeated over the last 10 years. String them together and you get “handmade for everyone[’s] complicated needs,” a fine description of his vision. Youds’s practice tracks a shift in the way we construe categories of object and experience, connecting the idioms of abstract painting and minimalist sculpture he has inherited to the screen interfaces and virtual spaces that have decisively altered the way we find art. In the midst of this shift, Youds has loosened up, progressing from highly finished constructions to assemblages that feel as much improvised as engineered. “handmade velvet satellite” articulates the free floating, futurist poetics and meditative tinkering that have become an increasingly prominent part of his aesthetic credo.

Punctuating a long wall are several works from a series Youds calls “thought balloons,” wall-mounted lengths of twisted metal bearing tilted discs the size of appetizer plates. With their flat, framed faces painted an iridescent white, black or yellow, they recall rimmed key tags, traffic signs and mirrors mounted on handlebars or in convenience store corners—declarative gestures of order and caution angled towards varied sightlines. In accumulation they articulate passes and pauses that position and reposition the viewer; if you stand further back, the dips, twists and folds are optically animated, and the casual nudging and blank regard of the thought balloons appeal persuasively: we like to look and, looking, we’re prone to mirror.

Robert Youds, installation view, “handmade velvet satellite,” 2022, Deluge Contemporary Art, Victoria. Photo: Todd Eacrett. Courtesy Deluge Contemporary Art.

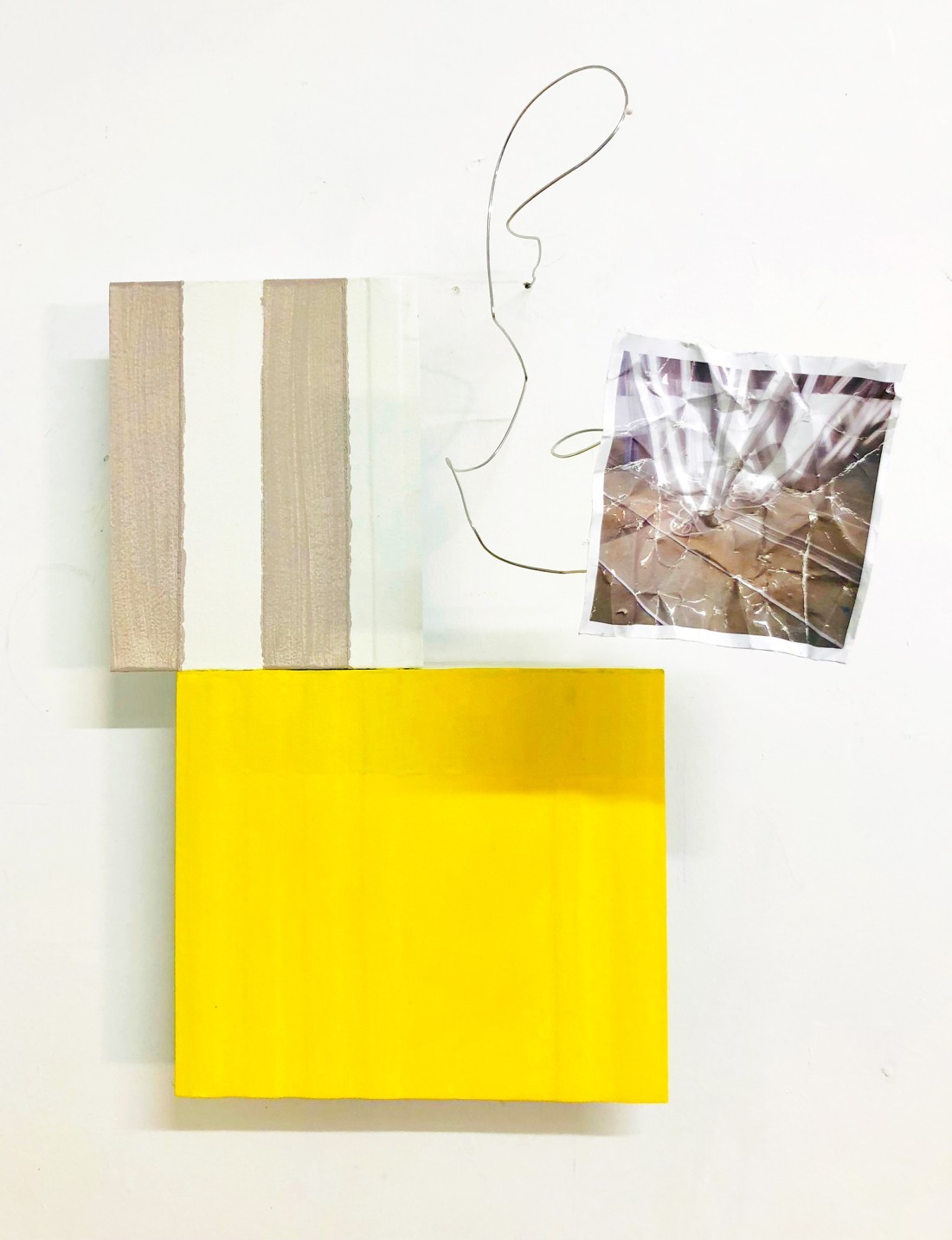

Where titles of the “thought balloons” like Readymade Monde, Passenger’s Horizon and Heat of the Night perform a ready-made rhetorical urgency, those of the “Machineflowers” series come across as plaintive missives. I Have Struggled, Heaven’s Memory or You Remember Me are titles Youds tells me are open to interpolation, approximate as subtitles of translated dialogue hovering beneath their speakers. Each presents a painted panel from which a calligraphic wire extends a crumpled A4 print of a digital photo of a rigged light construction. The scale and execution of the paintings seem pointedly modest, a provisional abstraction of dragged lines, lax painterly glazing and domestic colour, while the photos are descrambled as much as looked at; obliquely, they resemble Polaroids of digital bonfires. Drawn by these titular, forensic flowers, we’re led backward into surfaces of neutralized allusion. Are the paintings “paintings,” semaphores from the fraught, fought-over history of abstraction, or are they sincerely affecting? And, is the act of painting (especially painting pared to such rudiments) the only iteration of an answer? Youds has returned to the interrogation of abstraction by the postmodernism of his youth many times, always with an insider’s fluency and care.

This same hopeful irony lives in the repetitions and variations of Your Constant View is My New Underground I–IV, 2022, four stacked rows of four canvases each, offset by angles that recall the look of books propped open or turned down, or supports leaned as clean slates counting the days. Each surface turns to face some light as crudely contoured frames declare an unformed space—we wait with them.

Robert Youds, Machineflower, You Remember Me, 2022, honeycomb aluminum, paint, glass bead, wire, photograph, 20 × 20 × 1.5 inches. Photo: Robert Youds.

Youds writes, “The topics of both a hypothetical underground and satellites have been large on my 4th dimensional mind as of late. Maybe as metaphors for both places and things where unfettered ideas can be transmitted (experienced).” Curiously, fetters have in one form or another appeared many times in his work. Illusion’s Complicated Exchange, 2022, for example, is an array of three triangular spans of chain weighted with clusters of felt, Plexiglas, cardboard and, this time in miniature, painted aluminium panelling. The late Robert Linsley once categorized Youds’s work as narrative, and part of the complexity with which Youds thematizes abstraction is his interest in the blurred, frankly beautiful discourse between works of art and applied design. A favourite film of the artist’s is Playtime, Jacques Tati’s hypnotic take on postwar Paris as technological spectacle gone awry, in which a showroom can be mistaken for an office and a family’s modern flat is fronted by glass like a shop window. Critiques of capitalism aside, what’s spellbinding is the willingness of Tati’s characters to play along, like actors in an improv troupe, with their brave new lives. The forms of Illusion’s Complicated Exchange dangle, drape and gently graze the floor, pantomiming handbags, luggage tags or decorators’ swatch books in a thesis of grace against gravity and haste somewhere between the delicately seeking “Fallen Paintings” by Youds’s friend Polly Apfelbaum and a tangle of felt cut by Robert Morris tumbling towards its angle of repose, to be arranged, as the artist instructed, “according to taste.”

And despite the drama of fabrication on display throughout this space, taste, as a naming of choices, claims its stake: on one side an ineffable sublime of light, contour, structure and space; and on the other a desublimation of language once excised from the literary, now presented as punchline. The elegance of a disembodied cool is a signalling of this mystery; Youds is a pointed maker, but making is not the point. Over a dedicated career his collecting of tropes as much as materials has developed its own “echo,” a Youdsian word from which I infer “a memory of making moving outward.” Or forward. ❚

“handmade velvet satellite” was exhibited at Deluge Contemporary Art, Victoria, from September 9, 2022, to October 8, 2022.

John Luna is a visual artist and poet living on Malahat territory on Vancouver Island. His ongoing project The Servant addresses PTSD as experienced by veterans and their families.