Robert Rauschenberg

“Robert Rauschenberg: Combines” is a must-see exhibition. It serves to immerse the viewer in a body of work that broke from the intellectually dominant movement of its time—Abstract Expressionism— opening up an expanded playing field that would come to spawn Pop, Fluxus, Arte Povera and Performance Art. The term combines was coined by Rauschenberg to refer to both the “combination” of media and materials—sculpture, painting, collage and performance tethering together a wide variety of irreconcilable visual referents— and the industrial harvester called a combine which turns a field of wheat into a mountain of grain. Rauschenberg culled the materials for his Combines from the junk shops and streets of his adoptive home of New York City, while retaining the country-folk references—crocheted doilies, fruit-covered wallpaper and taxidermied animals (a hen, a rooster, a pheasant, a goat and an eagle all make appearances)—that relate to his upbringing in the coastal refining town of Port Arthur, Texas, in the 1920s and ’30s during the first major oil boom. While on leave from the navy in the 1940s, Rauschenberg visited his first museum, the Huntington Gallery in San Marino, where he saw the original portraits— Thomas Lawrence’s Pinkie and Gainsborough’s Blue Boy—that he knew from the backs of playing cards. In a flash he realized there was such a thing as being an artist, and that, by extension, the images he had seen in reproduction were actually made by a human hand.

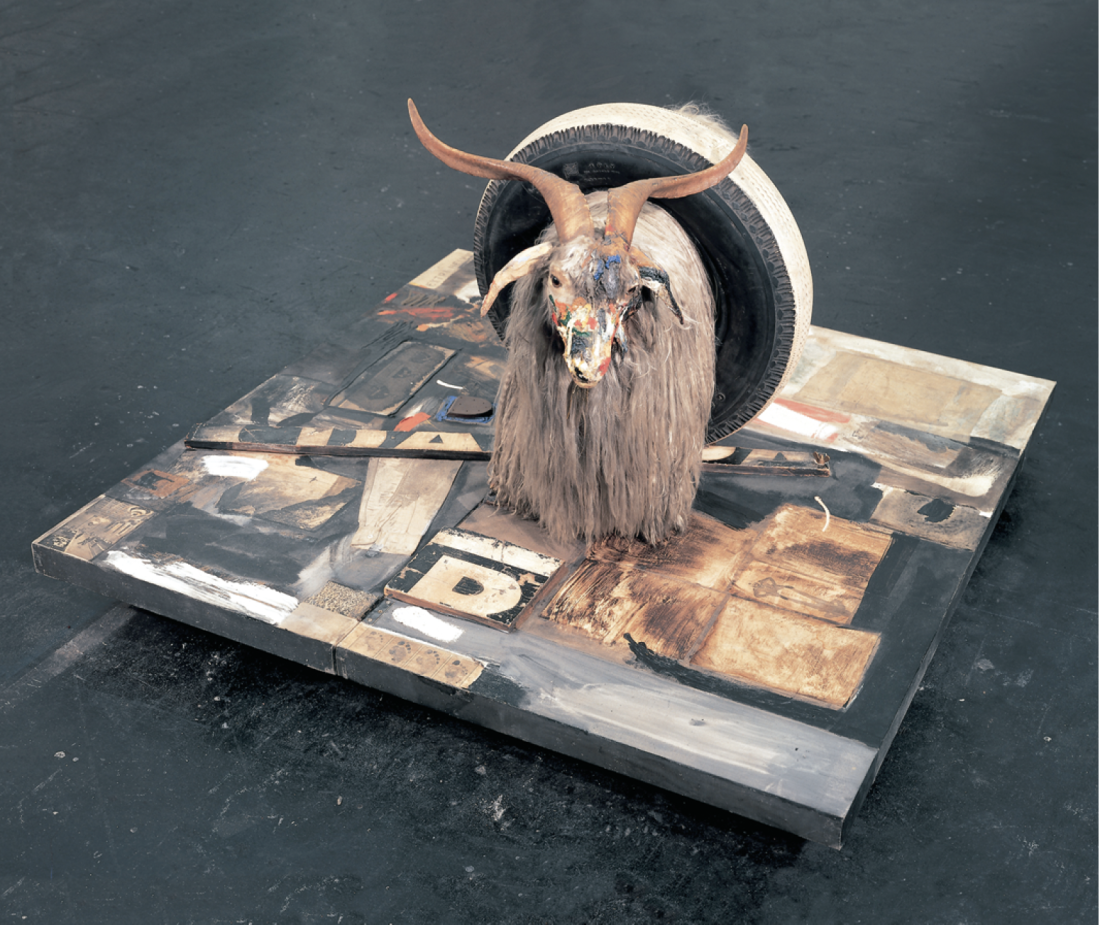

Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram, 1955-1959, oil, paper, fabric, printed paper, printed reproductions, metal, wood, rubber shoe heel, and tennis ball on canvas with oil on Angora goat and rubber tire on wood platform mounted on four casters, 42 x 63 ¼ x 64 ½”. Moderna Museet Stockholm. Photographs courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

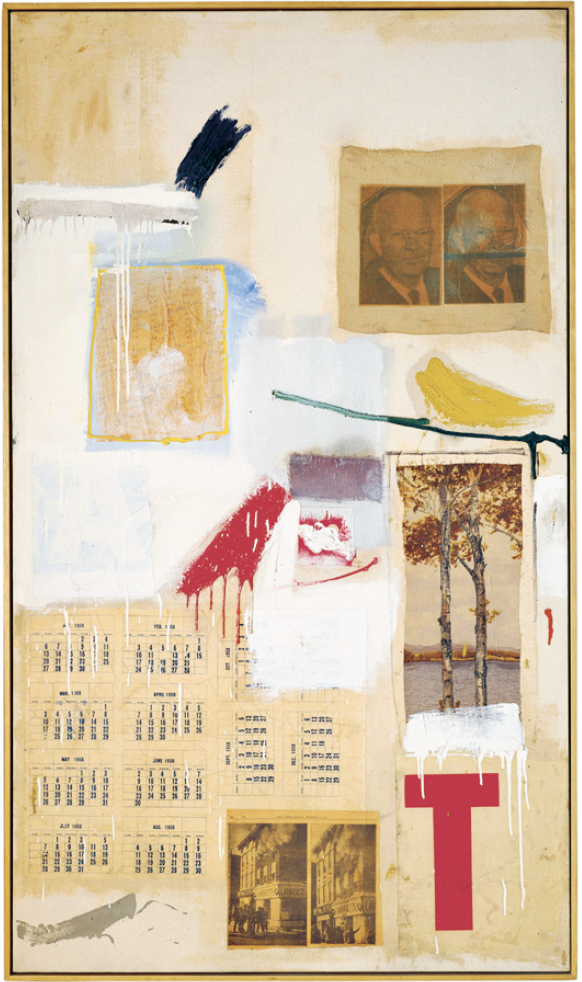

Rauschenberg would plumb this tension between originals and reproductions by incorporating them into his compositions, taking postcard-size images of well-known paintings—such as Renoir’s Girl with a Watering Can, which he used in Collection, 1954—collaging and overpainting them into a piece, turning them, by association, back into originals. Rauschenberg even went so far as to reproduce his own work, Factum I, in a second piece called Factum II, both from 1957. As indicated by the titles, for Rauschenberg paintings are a series of facts or deeds—whether it is a painterly brushstroke or a reproduced photograph—and not representations of a subjective interior world, as they were for the Abstract Expressionists, for whom materials themselves were imbued with emotional properties. As such, works of art are objective realities that can be duplicated without compromising their originality or immediacy. Describing his ideological distance from the New York school of Pollock, De Kooning and Rothko—and, by extension, from the Beat poets who came to be influenced by them—Rauschenberg told Calvin Tomkins: “I used to think of that line in Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, about the ‘sad cup of coffee.’ I’ve had cold coffee and hot coffee, good coffee and lousy coffee, but I’ve never had a sad cup of coffee.” As if to bring this idea home, each of the “Factum” paintings contains a trio of reproduced images. In the upper right is a pair of identical photographs of president Eisenhower. Beneath is a single colour image of two nearly identical birch trees. Along the bottom is a pair of sequenced newspaper photographs of a burning building. The twin Eisenhowers acknowledge the sameness of reproduction; the pair of trees introduces natural deviation; and the shots of the burning building allow for the intervention of time, which invariably interjects the unpredictability of change and chance. The burning building can also be seen as a bit of incendiary humour, a will to destroy what came before, with an awareness of the revolutionary nature of Rauschenberg’s own process.

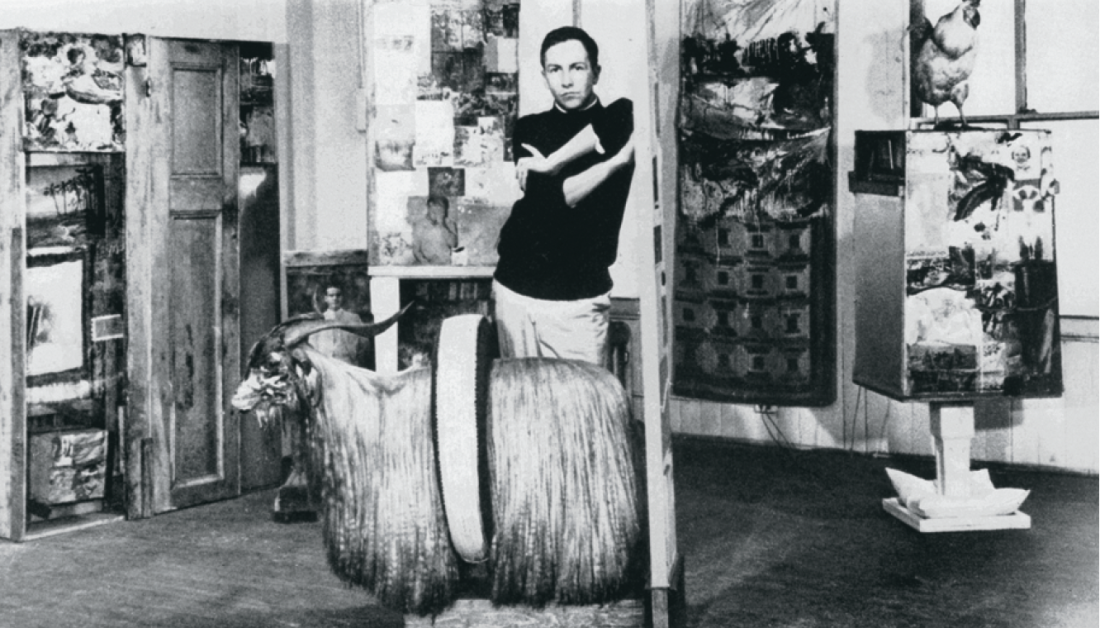

Robert Rauschenberg in his front street studio, New York, 1958.

This sense of pairing with a difference is something Rauschenberg’s work displays in abundance, constantly making room for irrational juxtapositions and incongruous meanings. In Untitled, 1954, and Odalisk, 1955–58, exhibited together for the first time since leaving the artist’s studio, Rauschenberg constructs a pair of his/her works which gamely confuse the issue of gender. Untitled, a two-tier box-like construction with scrims and hidden chambers, is collaged with masculine imagery of friends and family. In the lower box, a photograph of a dandy in a white linen suit stands like a rumpled Narcissus above a mirror reflecting both him and the bottom of a life-sized, stuffed Plymouth Rock hen standing to his right. In the back of the wooden box, suspended above the hen, are a pair of shoes and socks, both painted white, a sculptural rendition of those in the photograph of the dandy. The companion piece, Odalisk, features a box collaged with predominantly feminine imagery: a pair of luscious pin-up girls, a harp and the artist’s mother. These are mixed with the occasional masculine image, including one of a matador—an ultra-masculine male dressed in femininized clothing and fighting off the most unabashedly masculine of beasts, the enraged bull. The entire structure is mounted on a piano leg resting on a pillow, recalling the famous odalisques of art history—Manet’s and Ingres’s among them—who are laid bare, propped up on pillows, offering sexual services. A rooster—a cock—strides on the roof of the structure. This simultaneous embrace of both genders seems intensely personal, though in a witty, untortured fashion. It is the work of a man who slipped from one sexual role (the married man) to another (the homosexual man), and now happily conflates the two.

This sort of humour, and the spontaneous psychic rupture that it represents, abounds in “Combines.” Humour itself is explicitly referenced in the large number of works that have comic strips collaged into their surfaces. Read closely, many are laugh-out-loud funny. Monogram, 1955–59, one of the most legendary combines, is one such work of serious, giggling humour. The work, which went through several incarnations before arriving at its current floor-based form, centres on a stuffed angora goat which inhabited the artist’s studio for years before coalescing into a completed work. Its face is smeared with paint in a multitude of colours, as if it had been rooting around in paint cans. It stands on a platform—its own meadow—of daubed paint and collaged photos that can be read as a commentary on the artistic process: a tightrope walker (risk), an exhausted tennis player (effort, skill and play), a child’s footprints (innocence), an elaborate library (knowledge) and odd human cast-offs (the heel of a shoe, a shirtsleeve). Wrapped around the goat’s middle is an old tire, its treads painted white. This is a material Rauschenberg claims to have used because it could be found in abundance in New York City, but which also makes reference to a collaboration with John Cage from a few years earlier, in which Rauschenberg painted the wheels of a Model A Ford black and had Cage drive the print/ painting across attached sheets of white paper. A blackened tennis ball is “dropped” on the ground behind the goat: a scatological joke about man’s first creative gesture, and one that likens man to animal.

Robert Rauschenberg, Factum I, 1957, oil, ink, pencil, crayon, paper, fabric, newspaper, printed reproductions, and printed paper on canvas, 61 ½ x 55 ¾”. Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, The Panza Collection.

One of Rauschenberg’s many innovations was to incorporate performance, interactivity and time-based media into the combines. Minutiae, 1954, a freestanding work that features a soft, fluttery, multicoloured curtain, was originally created as a set for Merce Cunningham’s dancers. Though it exists as a sculptural form, it is not really complete without the presence of dancers to set the curtain in motion. Black Market, 1961, designed for an exhibition in Stockholm, relies on the random intervention of the audience. The work includes a suitcase filled with objects placed on the floor and tethered to a wall-hung element that includes four clipboards. Rauschenberg intended the audience to take an object from the suitcase and replace it with something else, recording the transaction on the clipboards. Quickly, the honour system broke down, items disappeared and weren’t replaced, and Rauschenberg shut the suitcase and concluded the performance, displaying the work as a closed system. With Gold Standard, 1964, the last of the combines, the making of the piece became a time-based performance. In a testament to Rauschenberg’s fame, he was invited to Japan to create a work of art on television for a program called Twenty Questions to Robert Rauschenberg. Rauschenberg combed the streets of Tokyo for his materials and performed the work as he created it during the time he filmed the program, attaching items to a multi-panelled gold screen—an homage to the esteemed Japanese art of screen painting—in lieu of answering the increasingly frustrated interviewer’s questions. The final assembly consists of work shoes, a road barrier, a Coca-Cola bottle, a clock, the interviewer’s handwritten questions and other objects attached to the screen. In what can be perceived as an illustration of the growing technological rivalry between the US and Japan, the artist pits the RCA dog tethered to the construction on the right against a battered cardboard box of Sony recording tape cantilevered off the screen at the left.

Increasingly, after this period, Rauschenberg’s attention shifted away from the combines and sculptural forms to explore the melding of painting with the arts of reproduction: silkscreening and photography among them, an interest that dominates his career to the present day. If there is any disadvantage to an isolated focus on the combines, it is that it makes one long for what has been exhibited amply in previous career retrospectives: that which came before and that which blossomed after this remarkable, fertile and immensely productive period of this seminal artist’s career. ■

“Robert Rauschenberg: Combines,” curated by Paul Schimmel, was exhibited at MOCA in Los Angeles from May 21 to September 4, 2006. It was previously exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and will travel to Paris later this year, and to Stockholm in 2007.

Susan Emerling is a writer living in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, ARTNEWS, and Art in America. She is currently working on a collection of short fiction.