Robert Mapplethorpe

With my own questions of identity in mind I viewed Mapplethorpe’s questioning of this theme at his recent exhibition, “Focus: Perfection,” at the Musée des beaux-arts in Montreal. The viewing eyes often filter an image through some gauze of personal experience either latent or potent, and a meditation on the self has become a central concern. Mapplethorpe’s grand examination of identity, which in his oeuvre is a topic that stands majestic, certainly warrants the crown of capital letter “I”—Identity. In his hands or through his lens, the question was not so much an existentialist or solitary version of “who am I?” but rather, how the self and the body that houses it figured at more or less comfortable positions within society, at a time when there was a tightening atmosphere toward culture, an atmosphere which exploded at the time of the artist’s death in 1989. What he revealed, notably by the flexibility of his own image and his chameleon-like ability to move comfortably between “uptown” and “downtown,” was that the self is a plastic entity, something that could be sculpted—a concept he applied to his artistic practice in a self-proclaimed movement towards perfection.

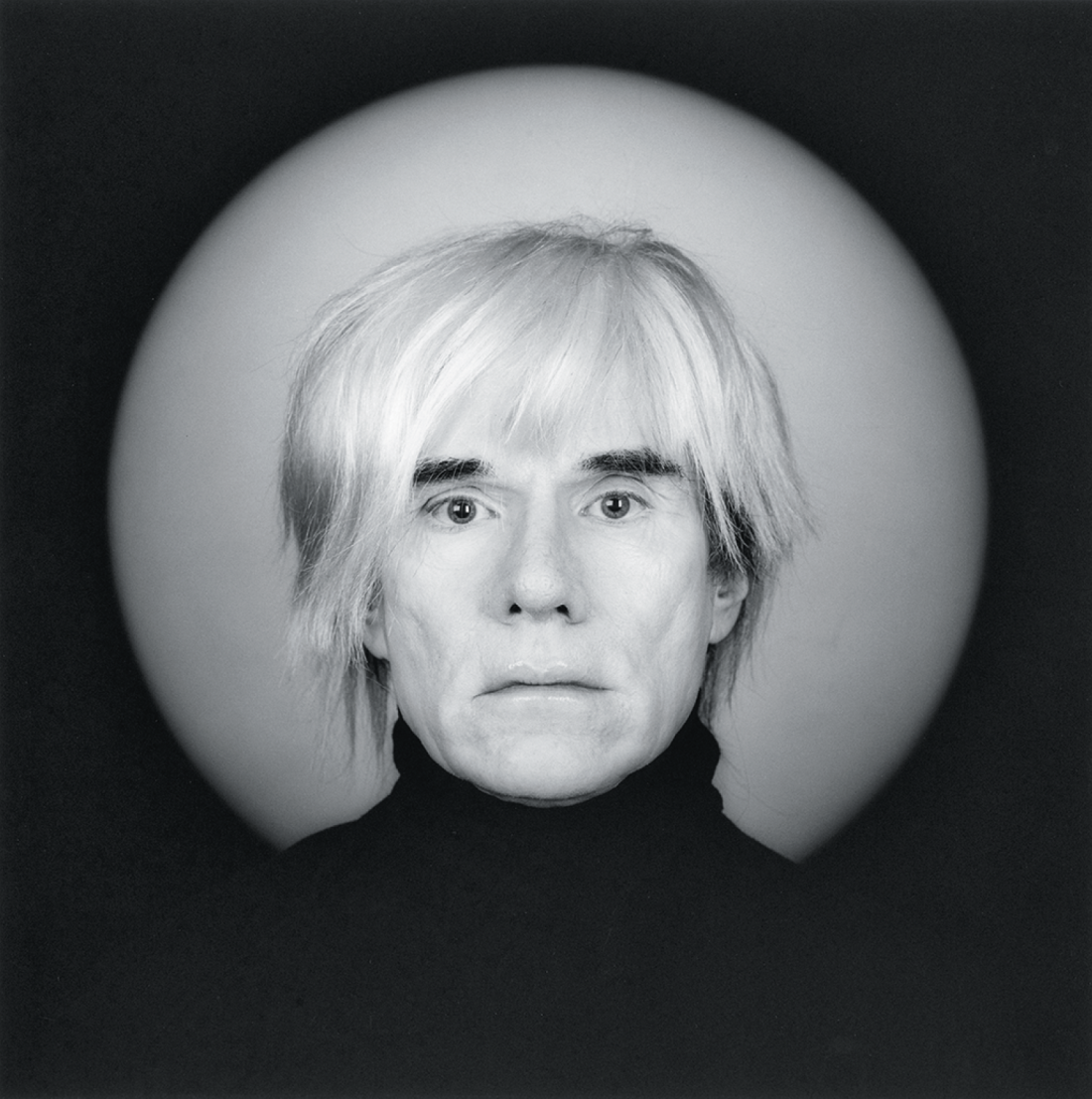

Robert Mapplethorpe, Andy Warhol, 1986, gelatin silver print, 48.9 x 48.9 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art and J Paul Getty Trust 2011.30.30. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission. Image courtesy the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Much has been said about Mapplethorpe the sensationalist, the artistic pornographer, and it seems even when we attempt to avoid the topic in order to highlight his talent with other subjects, we linger on sex. To be sure, the subject warrants this attention since Mapplethorpe brought to fine art some material which had been previously excluded or banished as being pornography. The Montreal exhibition dedicates one gallery of five to this work, but strives to highlight Mapplethorpe as an artist rather than the enfant terrible he was often known as (a persona in which he took authorship). His questioning in the ’70s and ’80s of race, gender, sexual orientation and social roles takes on new relevancy in our charged current era. What is most remarkable when we look at Mapplethorpe’s erotica within his oeuvre is the indiscriminate eye he applies across subject matter, as he famously explained in a 1979 interview: “ I don’t think there’s that much difference between a photograph of a fist up someone’s ass and a photograph of carnations in a bowl.” However, to a millennial generation and potential future audiences with minds formed on the jagged moving parts of video, I imagine what may provide the greater shock value is not the subject matter itself, but the acute formal stillness that holds the gestures. In the current post-photographic moment, sex, along with any activity possibly imagined, is performed without precise authorship and in serial fashion; when one clip fails to interest another can be found just a click away. Long gone is the “perfect moment” that Mapplethorpe sought and captured, and more lamentable yet may be the loss in identifying such moments due to our clumsy hunger to archive everything.

However, here at the Musée des beaux arts, there are many perfect moments to behold—intimate and quiet portraits that reveal Mapplethorpe’s preference for subjects with whom he had cultivated a relationship, or at least a conversation. My favourites are his various portraits of women which, through pose and gaze, seem to intimate human potential in actualization. There are of course many excellent photos of his longtime friend Patti Smith who, in her angular androgyny, never fails to make a compelling subject. Also on display are a range of photos of Lisa Lyon, who was an active collaborator and whom Mapplethorpe photographed more than any other subject. There is a gorgeous 1977 black and white photograph of Rebecca Fraser, whose sleepy eyes passively challenge, her right shoulder hidden by the leaves of a plant or tree positioned on the edge of the frame. There is something in the delicacy of the draping foliage as it covers her body that reminds me of André Kertész’s gentle Andre with Lamb (1923). Also notable is a photograph of a raw and darkeyed Caterine Milinaire (1976) positioned in front of heavily shadowed drapery, and another of a reclining Holly Solomon (1976), with a cigarette held upright between elegant fingers, in front of a panelled wall of floral wallpaper. These images work to show the women as complex individuals holding stories in their bodies, rather than as archetypes or caricatures, as they are often portrayed by less sensitive or more commercial artists. Although Mapplethorpe was not above such tactics, caricature was done always with a double take that thwarted anticipated interpretations of clichéd stereotypes.

Calla Lily, 1988, gelatin silver print, 49 x 49 cm. Jointly acquired by the J Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; partial gift of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation; partial purchase with funds provided by the J Paul Getty Trust and the David Geffen Foundation 2011.9.39. © The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used with permission. Image courtesy the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Among or within Mapplethorpe’s broad spectrum of subjects, the self-portrait takes on a special role in defining his own identity as he questioned his sexuality, assessed his shifting position in social strata, and finally confronted his impending death. One of the most impressive self-portraits is an image taken in 1988, not long before his death the following year. Here, Mapplethorpe’s head floats against a black background as he holds a cane topped with a carved image of a skull, positioned in the foreground. There seems some incredible distance between hand and head and the expression on his face, which he had originally intended to be “defiant” in the face of death, here turned more melancholy as the posing caused severe pain in his knees. Perhaps we see that ultimate transformation that must occur before the letting go, which is a kind of respectful capitulation to forces greater than even the master craftsman he was, although not without some remorse and artful resistance. ❚

“Focus: Perfection” is on exhibition at the Musée des beaux-arts, Montreal, from September 10, 2016 to January 22, 2017.

Tracy Valcourt lives and writes in Montreal.