Robert Adams

Elegiac—I’m not the first critic to use this word to describe Robert Adams’s black-and-white photographs. His scenes of the modern American West, of landscapes in Colorado, California and Oregon, ineluctably and sometimes brutally altered by humankind, are shot through with silvery light and shadowy loss. Although individual pictures are consciously restrained, the cumulative effect of Adams’s work is one of sorrowful nostalgia, as if remembering an Edenic time before our folly expelled us from the most glorious of gardens. Adams honours the “gift” of the natural world and at the same time confronts the blight that we have too often inflicted on it. Nearly 300 of his silver gelatin prints from the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven were recently on view at the Vancouver Art Gallery, the first stop in an international exhibition tour. Their settling here was a gift, too, like a flock of rare birds roosting briefly in our backyard before resuming their far migration.

Sometimes the lost garden metaphor identifiable in Adams’s work is literal, especially in his series “Los Angeles Spring,” shot in southern California in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Here, freeways, smog and heedless earthmoving obliterate the scented beauty of earlier citrus estates and eucalyptus groves. In Edge of San Timoteo Canyon, looking towards Los Angeles, Redlands, California, a few skeletal trees, stripped as if by napalm, stand sentinel on a hilltop, far above a highway under construction. In Santa Ana Wash, San Bernardino County, California, garbage and the stained and splintered remains of both building materials and natural growth lie strewn across a previously pastoral landscape, torn up again in the service of a new highway.

Characteristically, the paradise Adams mourns is not cultivated in the Old World sense but rather shaped by a New World idea of the frontier that is all huge Coloradan vistas, high plateaus, dry mountains dotted with sagebrush, and creek beds flanked by cottonwood trees. This West is unbounded, stretching outward, upward towards cloudless skies, and baptized by the cleansing light of a young sun. It’s the West Adams fell in love with as a boy when he moved with his family to Denver from Madison, Wisconsin. It is also a West whose evidence of earlier rural settlement—a grain elevator, dry leaves blown across an unpaved country road, the foundations of an abandoned farmhouse—has occurred at a scale that allows a certain austere romanticism to adhere to his record of it.

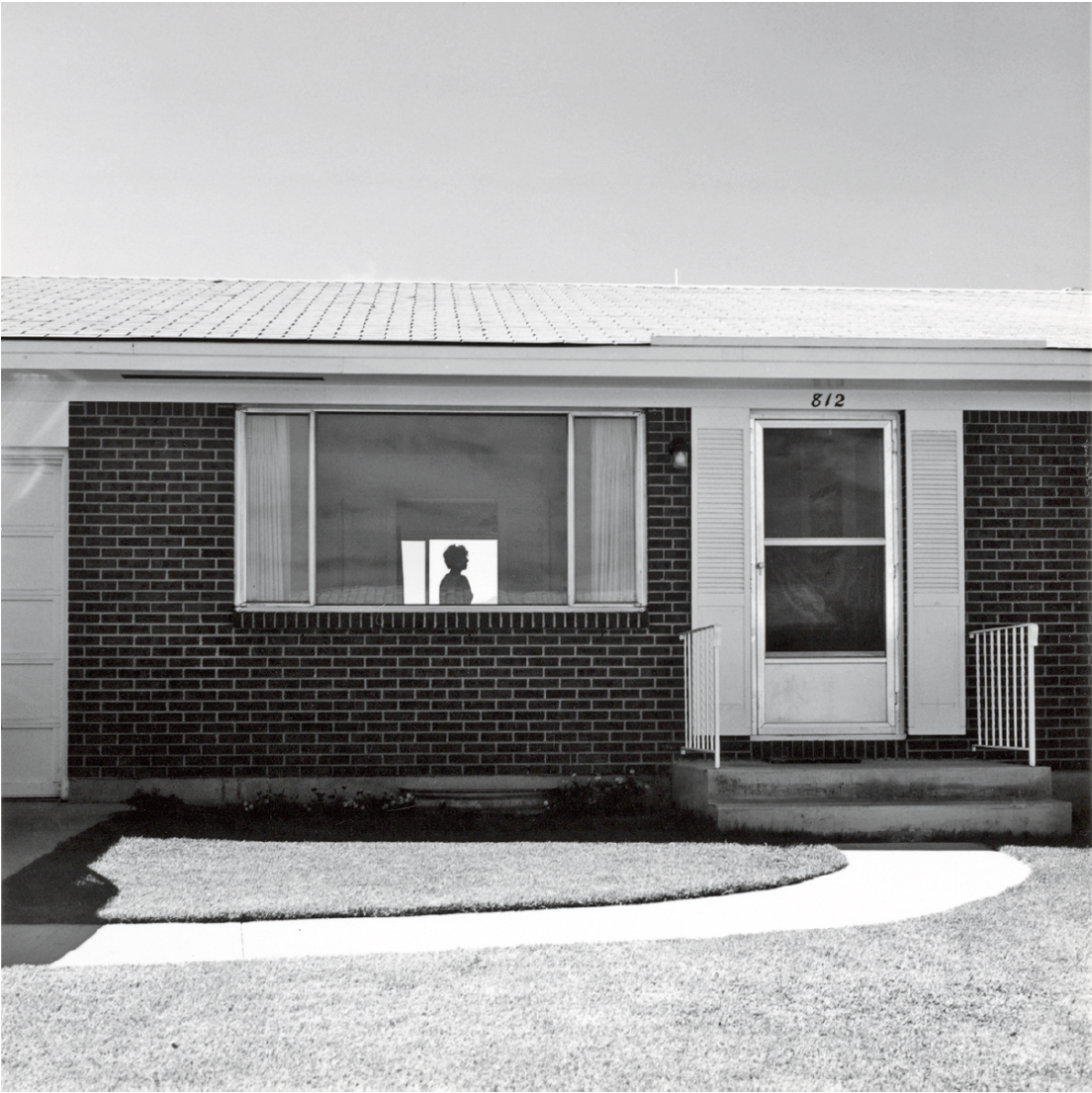

Robert Adams, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1968, gelatin silver print. Yale University Art Gallery. Purchased with a gift from Saundra B Lane, a grant from the Trellis Fund, and the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund.

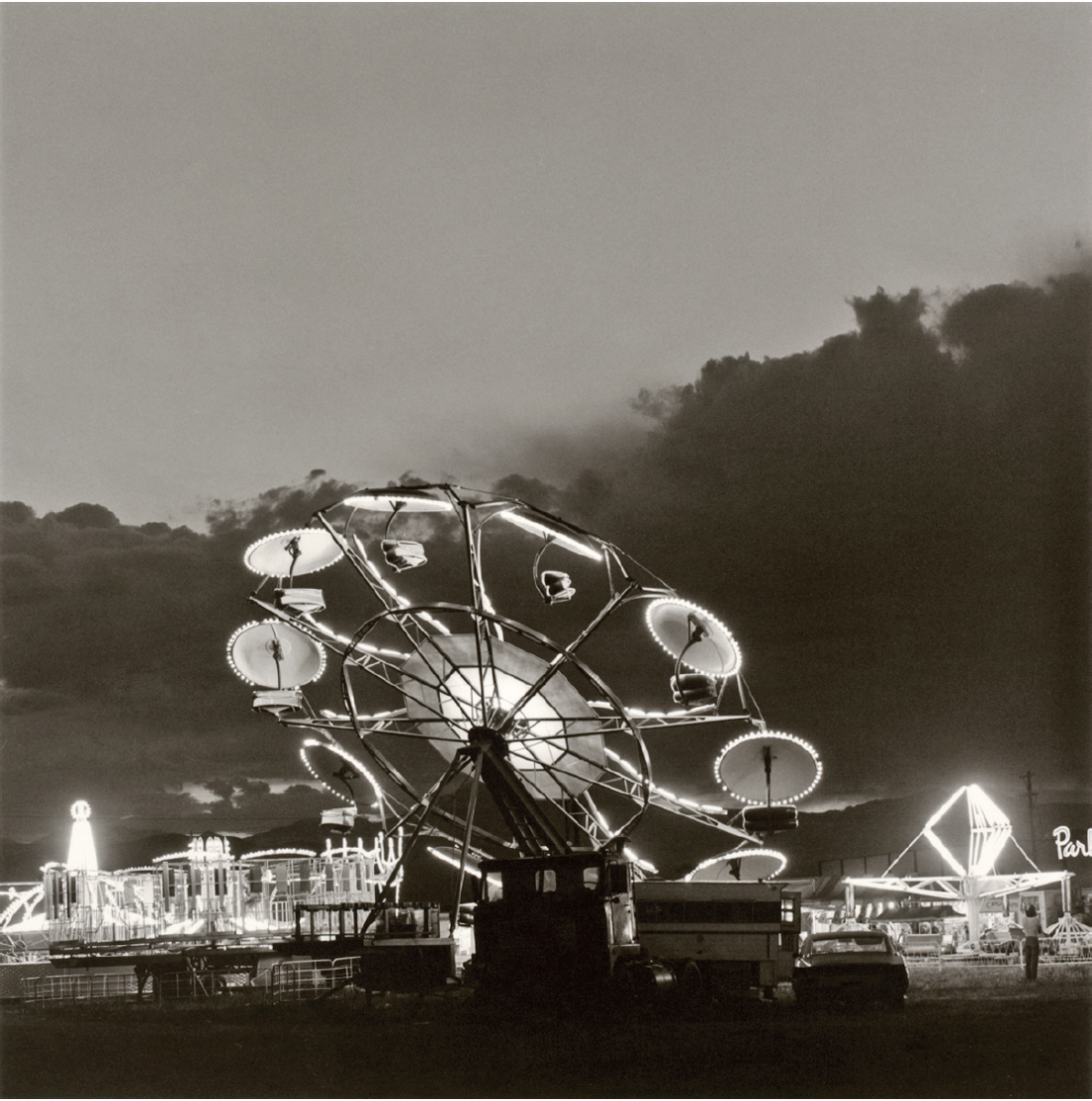

This record stands in sobering contrast to the vastly man-altered landscapes that we associate with this artist, especially his New Topographics-era photos of tract housing, strip malls, highways and fast-food restaurants—all that rapid and unpicturesque suburban development in the Denver and Colorado Springs areas that compelled his lens for so many years. It also contrasts with his photos of more wanton destruction: graffiti spray-painted across rocky outcroppings on a mountain lookout, a mesa top scored by the tracks of mining trucks, a bright sky partially blackened by a cloud of burning oil sludge. One of Adams’s most ironic—and paradoxically beautiful—photographs is Pikes Peak, Colorado Springs, 1969. It shows a Frontier gas station at dusk, its fluorescent sign glowing in eerie counterpoint to the dark mountain and ebbing evening light beyond. A lament for an idealized notion of the frontier—and a hint that unsustainable development started with Manifest Destiny—is also seen in his shot of a single buffalo in a fenced field in Buffalo for sale, Pueblo County, Colorado.

Still, even the most damaged of his landscape subjects is articulated by the light that is so particular to the West and that equally compels Adams’s camera. His images of cancerous new suburbs eating their way across plateau and grassland against the backdrop of the Rocky Mountains are heart stopping in the clarity of the light, the unclouded vastness of the sky and the heroic stretch of the horizon. An exception is a series of photos taken in or near Denver in the mid-1970s and titled “What We Bought.” Here, as the Yale University Art Gallery’s Jock Reynolds and Joshua Chang pointed out when touring a couple of Vancouver critics through the show, Adams has excluded the radiant light and far horizon and employed a purposefully close focus and narrow range of greys to emphasize the reality of his subjects: smog and pollution, discount stores and fast-food restaurants, and garbage dumped in grassy fields and arroyos. “The West has ended,” Adams writes, “…as the nation’s vacant lot, a place we valued at first for the wildflowers, and because the kids could play there, but where eventually we stole over and dumped the hedge clippings, and then the crankcase oil and dog manure, until finally it has become such an eyesore that we hope someone will just buy it and build and get the thing over with.”

Robert Adams, Longmont, Colorado, 1979, gelatin silver print. Yale University Art Gallery. Purchased with a gift from Saundra B Lane, a grant from the Trellis Fund, and the Janet and Simeon Braguin Fund.

Adams’s vision of our more measured incursions into the landscape, of a human scale and thoughtful relationship with the natural world as seen in Methodist Church, Bowen, Colorado, in which the modest white building is shaded by a tall poplar tree, was apparently consolidated in 1968 when he visited Sweden for the first time. A theme that emerges in his work is of the conflict between hope and despair, between what is beautiful and blessed about our place in the natural world and what is greedily miscalculated and therefore damned. I don’t use these biblical phrases lightly: it seems to me that Adams’s intentions are profoundly moral. In his books of photographs and his poetic essays on the nature of his art, he has meditated on the photographer’s “civic duty” to his subject. “I began making pictures because I wanted to record what supports hope: the untranslatable mystery and beauty of the world,” he tells us in the introduction to What Can We Believe Where? Photographs of the American West “Along the way, however, the camera also caught evidence against hope, and I eventually concluded that this too belonged in pictures if they were to be truthful and thus useful.” Posed against the longing for a socially and environmentally responsible approach to the way we occupy the natural environment is the evidence of the unaltered beliefs that have ruled the American West during the past two centuries, especially the entwined religions of westward expansion, unfettered individualism and unregulated capitalism.

Adams’s move to Astoria on the Oregon coast in 1997 is marked by a shift in subject matter, from the disturbance that is suburban development to the “rape of the rainforest.” Some of his shots of clear-cuts in Oregon’s Clatsop and Coos counties are lit and framed in a manner reminiscent of American Civil War photographs, especially those by the Scottish-born Alexander Gardner. Rather than documenting swollen and broken bodies scattered across battlefields, Adams depicts the ragged remains of trees—ragged stumps, severed branches, shattered trunks—strewn across clear-cut hills and mountainsides. The metaphor of slaughter is powerful, as are the connections Adams poses between environmental destruction and the waging of war. That his sense of moral outrage is essentially Christian is manifest in the crucifix-like configuration of a tangled old-growth stump in Coos County, Oregon, circa 2001.

Writing in 1986 about the scenes he captured in “Los Angeles Spring,” Adams expressed again the sense that we have betrayed the Edenic gift of the natural world, a betrayal that is reiterated in “Turning Back,” his Oregon logging series. “All that is clear is the perfection of what we were given, the unworthiness of our response, and the certainty in view of our current deprivation that we are judged.” ❚

Robert Adams: The Place We Live, A Retrospective Selection of Photographs was at the Vancouver Art Gallery from September 25, 2010, to January 16, 2011. It is scheduled to travel to Denver, Los Angeles, Madrid and the United Kingdom.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.