“River Underground”

“Nothing remains the same: the

great renewer,

Nature, makes form from form,

and, oh, believe me

That nothing ever dies.”

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book 15

(Rolfe Humphries translation)

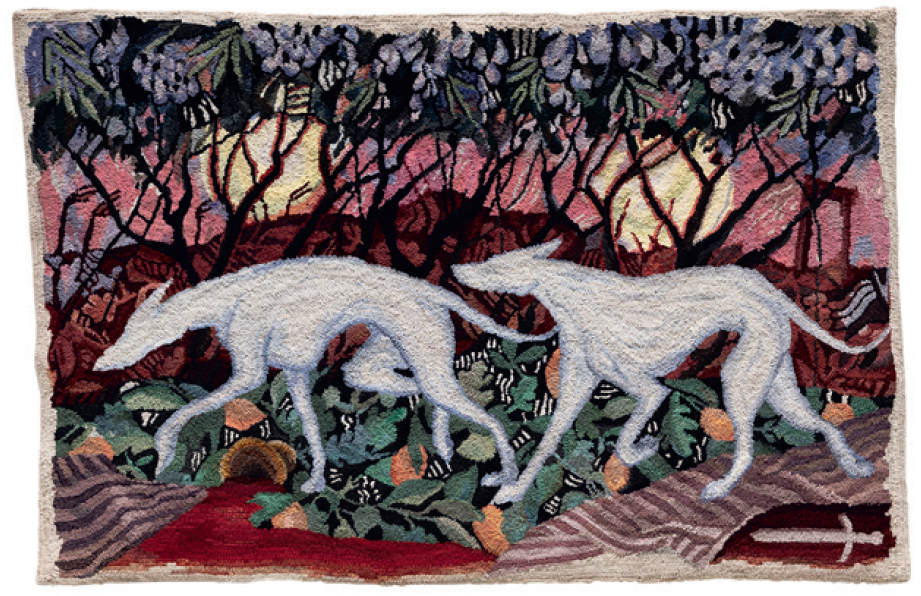

Heather Goodchild, Ghost Dogs, 2022, wool and burlap, 41 × 62 inches, “River Underground.” Photo: LF Documentation. Courtesy Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto.

A closer look at Margaux Smith’s paintings in “River Underground,” the two-person exhibition by Smith and Heather Goodchild at Clint Roenisch Gallery, reveals a curious frog motif. Frogs, the artist tells me, are a symbol of fertility women have historically worn for protection during pregnancy and birth. The act alludes to the mortal danger implicit to transformation. However, “death” does not exist as such, so says the Roman poet Ovid in his 15-book epic narrative Metamorphoses, only change. Ovid’s mythological narrative, dream analysis and a veneration for artisanal practice make up the basis for the fruitful collaboration between Smith and Goodchild.

The exhibition coincided with Smith’s first pregnancy; she gave birth within days of the opening. The creation of her work was inseparable from the gestation experience, manifesting in the natal palette and sensual subject matter of her paintings where layers of paint, drawing and collage were painstakingly applied to produce subtly shifting surfaces. Nude figures devoid of shame frolic passionately in her smaller watercolour works, and stand humbly before immense, fecund landscapes in her larger oil paintings. Reservoir, 2022, features a cerulean body of water in the unmistakable shape of a womb, its contents owing from an umbilical cord-like river, giving life to the surrounding abundance. The scene is evocative of the “Golden Age” described by Ovid, while the areas cast in foreboding shadows signal utopia’s inevitable end, as the injuries of human desire bring forth the “Silver,” “Bronze” and “Iron” ages. If a kindred utopia is felt in Goodchild’s textile works (the product of nighttime rug-pulling sessions) like Old Friends, 2022, so, too, is an impending collapse observable in the apocalyptic pink sky behind fleeing animals in Ghost Dogs, 2022.

Margaux Smith, Reservoir, 2021–22, oil on panel, 48 × 60 inches, “River Underground.” Photo: LF Documentation. Courtesy Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto.

While myth and history are heavily present in both artists’ work, the otherworldly, even planetary landscapes of Smith’s Leda’s Egg, 2022, and Ginger Lake, 2022, allude to periods in the future or out of time altogether. Their silhouetted figures, not quite human, bring to mind the dream-soaked works of 20th-century surrealist Max Ernst, or the heady, mid-century psychedelia of West Coast artist Bodhi Wind, whose pool-spanning murals populate the desert landscapes of Robert Altman’s 1977 masterpiece 3 Women. The film makes a good companion to this exhibition in its shared exploration of the leakiness between dream and waking life, past and future, self and other.

Where Smith’s and Goodchild’s work diverges is in the most curious element of the exhibition—a noisily patterned curtain on which several of Goodchild’s small, thoughtfully painted images are clustered. The compositions of the paintings are the unmistakable result of photographic reference material, while the posture and aura of the featured subjects are inextricable from the network technology we know them to be immersed in: the figure in Goodchild’s NY in NY, 2022, sits absent-mindedly looking down at her lap, where we imagine a smart phone to sit; the cropped, horizontal torso of a woman in Dreamer, 2022, suggests an image taken alone via laptop; the figures in Basement Cafeteria, 2022, look everywhere but at each other, submerged in a half-consciousness that is felt to alienate them from the rivers above and below ground.

While capturing a quiet wakefulness that prefigures sleep, these images likewise display a lack of resonance between the subjects and the surrounding environment. By contrast, the figures in Goodchild’s dream-inspired textile work Midnight Encounter, 2022 (an insolent pig and a nude nymph who shields herself out of shame or fear), stand in vital relation to one another and to the viewer as the pig’s stare engages us in a primordial dynamic of triangular desire and rivalry. Waking life is thus presented as sleepy, a realm where violence is transmuted into aggressive acts of technological innovation, interrupting organic life cycles and relegating their concomitant brutality to the past, myth or the unconscious.

Installation view, “River Underground,” 2022, Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto. Photo: LF Documentation. Courtesy Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto. Left to right: Margaux Smith, Reservoir, 2021–22, oil on panel, 48 × 60 inches; Heather Goodchild and Margaux Smith, River Underground, 2022, bricks, water pump, pond liner, ceramic and raku vessels, paint, water, dimensions variable; Heather Goodchild, Midnight Encounter, 2022, dyed wool and burlap, 51 × 32 inches.

The separation of these paintings depicting time and place, reified via a technological lens, from those dream- and myth-laden works where place and period morph and blend creates a binary that feels antithetical to the “leakiness” promoted elsewhere in the exhibition. Then again, if the literal sectioning-off of the photographic paintings feels heavy-handed, we are obliged to recall how rude an awakening from sleep can feel.

A bridge between Goodchild’s waking-life paintings and both artists’ dream compositions is located in their collaborative work—a disassembled brick “fountain” in the centre of the gallery topped by hand-thrown clay vases painted with narrative scenes reminiscent of Greek amphorae and under which a slight stream of water flows. The structure feels emblematic of popular notions of “civilization,” not least in its evocation of the Roman aqueducts that facilitated the society wherein Ovid penned his magnum opus. The summoning of civilization’s decline and collapse brings to mind one of said opus’s myths not explicitly alluded to in the artists’ work—that of Icarus, the boy who flew, via his father’s invented wings, too close to the sun, resulting in his tragic end.

From this vantage point, what at first looked to be the remnants of a past civilization in the pile of bricks, vases and a barely audible trickle at the centre of “River Underground” is rendered the future remnants of this one. If so, comfort can be found in a return to Ovid, whose passionate tales of metamorphosis illuminate that, while “nothing remains the same,” “nothing ever dies” either. ❚

“River Underground” was exhibited at Clint Roenisch Gallery, Toronto, from December 1, 2022, to February 11, 2023.

Jessica Baldanza is a writer from Toronto.