Richard Purdy

This stupendous art project was installed in four cavernous rooms that were part of what was once the Pittsburgh Reduction Company aluminum factory in Shawinigan, Québec. As the demand for and distribution of aluminum expanded during and after World War I, this factory was renamed the Northern Aluminum Company, then Alcan, after which its history and relocations got as complicated as every other late 20th-century mega-corporation.

The four rooms remaining since 1901 are now a national historic site and art venue that has offered 25,000 square feet of exhibition space since 2003. Inhospitable to mere accumulation of art objects, this is a magnificent, virtually self-sufficient architectural wonder built of timber, brick and cement, spanned by riveted steel truss work. In such a grand edifice a faint-hearted installation would wither.

Richard Purdy is anything but faint of heart. In the entrance room, the exhibition is introduced with his project from the 1980s, The Inversion of the World, a large relief map manifesting all the continents and islands as bodies of water and all our oceans, seas and lakes as landforms. This topsy-turvy interpretation of our world demands poignant, possibly tragic, self-consciousness that all animals, including ourselves, are more or less 80 per cent water. Water, as this map—as the entire exhibition—reminds, is indeed our lifeblood, worthy of devotion and stewardship, worthy perhaps of worship.

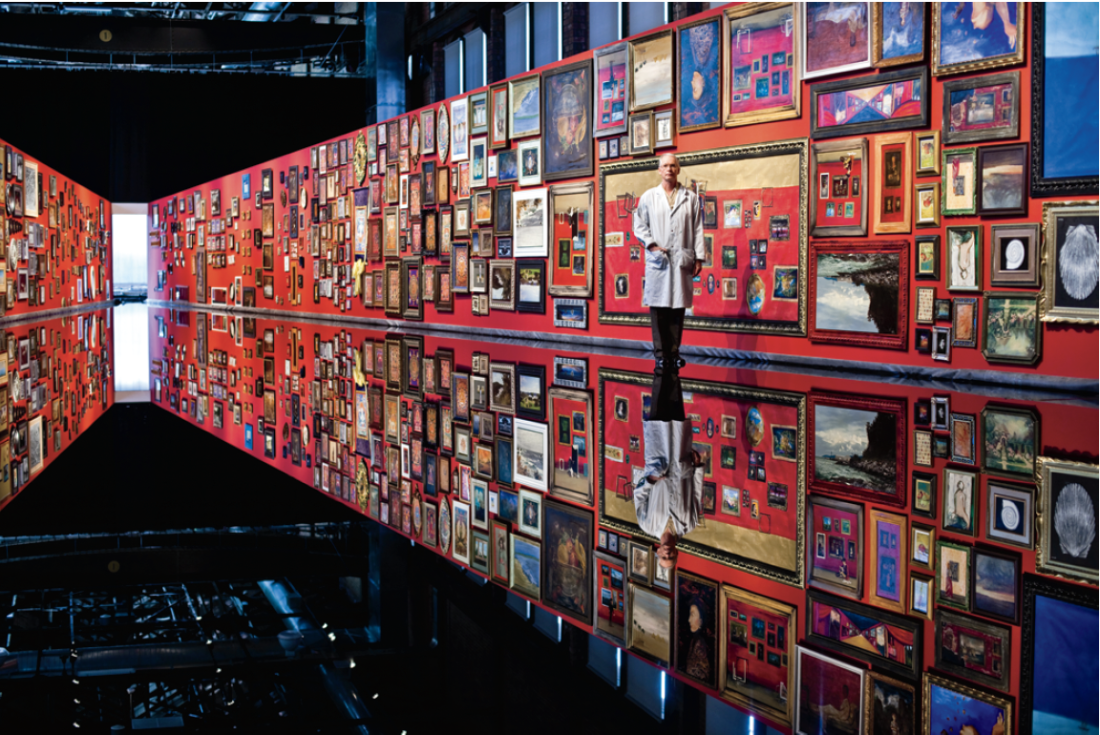

For the first of the next three rooms, an installation titled Unrestored, Richard Purdy produced 709 oil paintings and found a luscious antique frame for every one of them. Painted in “academic style,” these seemingly venerable artworks are genuine fakes, genuine because they are not copies of actual 17th- or 18th-century works, but fake because they were painted to look as if they existed (and began deteriorating) 200 or more years ago. The paintings have all been hung upside down salon-style on two 148-foot-long scarlet walls (within, but not hiding, the building’s actual brick ones). Through a four-person-size rectangular hole in the back of this room, the viewer could walk into the next room. A 12,163-square-foot expanse of logs is strewn across this next floor. Titled Aquidia, this phase of “ecH20/l’echo-l’eau,” is actually a huge number of trees cut in 1864 such that the outer trunk, bark and all, remains, but the underside was sliced flat, thus this “log jam” is settled quite immobile on the floor. At the far end of this radiantly sunlit room, beyond the region of logs, a light rain was falling (sprinkling from an apparatus on the ceiling) and because umbrellas had been provided for everyone who navigated the entire stretch of logs, a casual drama was evoked, as if sunshine, rainfall and red umbrellas were an occasion for extemporaneous choreography.

Richard Purdy, UNRESTORED, 2010, two converging walls of 148 feet, 709 framed oil paintings (originals), floor of EPDM rubber 45 mm, 738 gallons of water, in situ installation: 40’ 8” x 144’ 3 1/2” (5,868 square feet). Photograph: Olivier Croteau. Courtesy the artist.

The installation in the third room, titled Bindu: The Big Bang, is almost impossible to describe except by simile: floor like a gargantuan Technicolour atomic particle cloud chamber; floor like an inundation of a gazillion iridescent sea animacules hatching simultaneously; floor like the vision of Los Angeles seen from the cockpit of a plane at 10,000 feet; a vast LSD hallucination of heaven as witnessed by birds flying higher than God. And somehow more believably, a floor that seems an infinitely deep and infinitely ancient rainbow of sparks that became our universe.

This three-room spectacle was not only gorgeous, it was also obviously assembled with infectious delight and love of surprises. As for how the materials, both natural and concocted, were utilized, nothing, absolutely nothing, was makeshift.

Who wouldn’t be eager to see what it feels like to walk into such lavish surroundings when all three rooms were flooded with half an inch of water? Every visitor sloshed into the exhibition barefoot (or if they were fastidious, wearing the boots or crocs provided at the door). Twenty-five thousand square feet of floor were sealed by an EPDM rubber geotextile (visibly labelled “fish safe”). Being sealed like this, the whole underwater floor space was a pristine, perfectly reflective slough. The 530 gallons of clear water that eddied round the feet of the visitors, logs and raindrops were nevertheless calm and contained. Fire hydrants, electrical wiring and light bulbs stayed as safely dry as they would in any ordinary place.

The 709 oil paintings hung upside down were readily interpreted when viewed upside-right reflected in a 4,555-square-foot pond. Every one of these paintings pictured or alluded to stories of water: Italianate seascapes, fishes common and exotic, swimming serpents, maidens afloat, drowning sailors, SpongeBob Squarepants and friends, storms over oceans, bathing beauties (including Olive Oyl), ships and skiffs, canoes and rafts, all and more painted in different sizes and perfect colours. Meanwhile their surfaces are wrinkling and peeling (although ever so slowly over the course of this 13-week show) in homage to damage from floods, monsoons or the humidity of swamps. The idea of water becomes a metaphor accounting for almost everything in life: aren’t genes a kind of rivulet running through families? Isn’t violence a river that courses through nations? Ideas seep from one mind into the next; flocks of birds undulate in waves; the history of art streams through the history of everything else.

Richard Purdy, AQUIDIA: LA DRAVE, 400 fir tree logs authenticated 1864, floor of EPDM rubber 45 mm, 738 gallons of water, in situ installation: 40’ 8” x 112’ (4,555 square feet). Photograph: Richard Purdy. Courtesy the artist.

Speaking of history, the history of Shawinigan is founded on logs. The logging industry developed in 1852 upon completion of the area’s first waterslide on Rivière Saint-Maurice; many a logger’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren were splashing through this exhibition. Traversing Aquidia, balancing with their umbrellas, they tiptoed from one log to the next, the older ones with tears in their eyes. This is a log run with nowhere left to go except into historical reminiscence and idiosyncratic dreams.

As with the paintings, the more one stares at logs, the more they reveal: bug and woodpecker holes, of course, slashes from sharp tools, vestiges of fungi, evidence of amputated branches; or the surface of the log can seem like a sea serpent’s skin, or the bulge in a log seem like a miniature island village—the possibilities seem limitless.

Bindu: The Big Bang room was lit by 108 black lights; that’s what caused the intense blue lines along the ceiling and their reflected counterparts flashing through the water; that’s what caused millions of teeny-tiny sunken, shining, drifting plastic squiggles to emit their colours. These unidentifiable shapes swirled in eddies round people’s soles, glowing abnormally like toxic waste and underwater galaxies alike. Richard Purdy revealed to me their source: 40,000 dollar-store glow-in-the-dark jiggly playthings, some of which were actually likenesses of fish, ocean worms, seahorses, etc., all little sticky toys sliced up in minute pieces and thrown into the Bindhu: The Big Bang pool.

“ecH2O” demonstrated RichardPurdy’s understanding of so-called public art. It seems that the cliché “everybody is a critic” is all too true (while there will never be the cliché “everybody is an astrophysicist”). It is also rather obvious—and touching somehow—that just about every citizen actually believes art belongs to them. Given this, artists know how easy it is to get away with entertaining gadgets and nondescript ideas. But simultaneously to evoke free association, ideas, philosophies and references to art history—this is something that takes a lot of thought and experience. Yet even the latter is not, per se, respect for “the public.” “ecH2O” is a lesson in magnanimous respect for the public. This exhibition, which by word of mouth has already attracted more than 15,000 people to visit Shawinigan Space, was one of the most generous, quietly mischievous and humbly intelligent extravaganzas anyone would ever want to wade into. ❚

“ecH2O/l’echo-l’eau” was exhibited at Shawinigan Space in Shawinigan, Québec, from June 19 to September 26, 2010.

Jeanne Randolph is a Winnipeg intellectual whose most recent book is Ethics of Luxury: Materialism and Imagination.