Rhonda Weppler and Trevor Mahovsky

Rhonda Weppler and Trevor Mahovsky’s first solo show at Susan Hobbs was a tour de force. Continuing their investigation into iconographies of still life, their sculptural statements stretched and subverted the genre in seductive and stimulating ways. Heartily on hand was their ongoing drive to apply complex and complicated methods of casting to utterly ordinary things. This drive has been motivated by multivalent concerns with problems of process and performance and, in this exhibition, their painstaking practice was often enacted on a grand scale, yet suffused with a surprising sense of closeness and care.

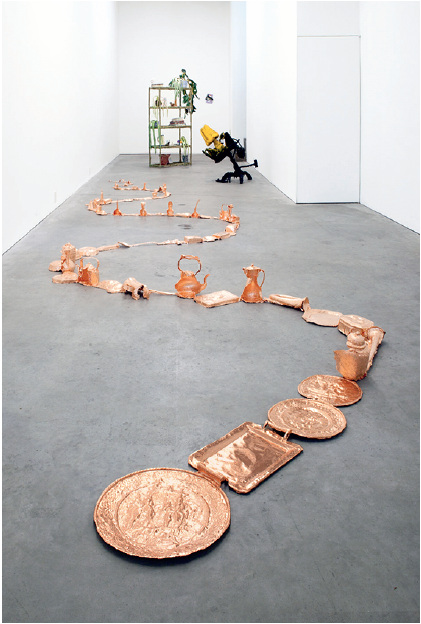

Rhonda Weppler and Trevor Mahovsky, installation view, “The Guest’s Shadow,” 2017, Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto. Photos: Richard Winchell. Images courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery.

Composed of a single, unbroken sheet of copper foil, the show’s titular work—The Guest’s Shadow (all works from 2017)—was made by gently and gingerly applying the delicate metal to a series of household items. Snaking along the floor, the foil took the form of things of decreasing size, from an ample platter to a miniature spoon. One by one, partial impressions were taken—of only one side of the thing in question—resulting in imprints retaining the texture of sundry sources, all of which were composed of copper: pennies, bugles, Bundt pans, baking moulds, among others. Clinging to one another in a playful manner recalling a toy train set, the conglomeration conveys a fragmentary and fragile feeling. This collection may be meant to materially sum up someone’s life, a tender testament—in a poetic and literal sense, given the vulnerability of the glistening foil—providing phantoms of possessions once handled daily. The work may also be read as a monochrome and minimal serpentine shape: this crushable creature could never be mistaken for a monument in the conventional sense, and, prompted by the title, it opens up a space for speculation. It may be a memorial to a dear and departed guest, with “shadows” of objects serving as aides-memoire. In this sense, the work recalls Roni Horn’s floor-based Paired Gold Mats, for Ross and Felix, 1994–95, based on mere floor coverings—normally subject to the wiping of feet— rendered precious by the artist with paper-thin metal, and yet morphing into an abstract and moving memorial. Weppler and Mahovsky’s crinkled expanse—which is relatively arduous in its arrangement and therefore touching in a different way—similarly shimmers when visitors kneel and scan its surface up close. The material and experiential realities of carefully (and collaboratively) casting and embossing become subjects in themselves and hence serve as a vehicle for personal reflection about how and why such objects operate, either privately within (in the mind or home of a collector, for instance) or publicly without (in the museum, gallery or shop).

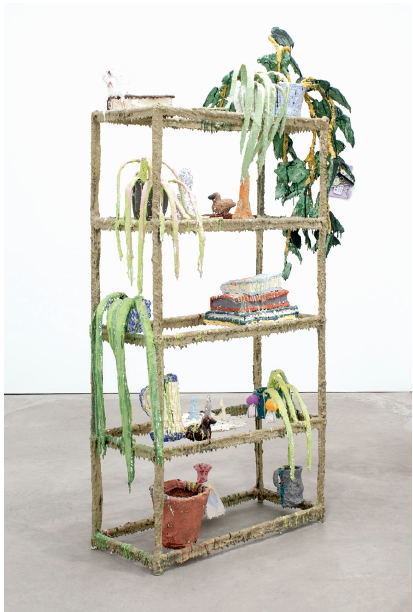

The Known Universe offers another portrayal of domestic stuff, here installed upon a steel shelving unit. The artists applied aluminum mesh to a range of objects (potted plants, picture frames and the like) and then fused these casts to the steel frame. The assembled structure became a support surface for the slathering and pouring of pigmented gypsum, gestures that initially come across as acts of degradation. On the other hand, their mark-making activity could be read as an anointing rite. To “anoint” is to cast a liquid onto something or someone whom one wants to sanctify, or, more generally, whose symbolic status one wants to modify—as in the case of baptism, sending the dead off to heaven or the consecration of altars. This flexibility between people and things, subjects and objects, is relevant to their practice—as they abstractly anoint a wide range of mundane materials in a manner that acquires a transgressive charge. Yet, the downward dripping of multihued plaster could be read as a kind of trashing—again, this may apply to an idea, person or thing—associated with cultures of camp, parody and satire. In this context, some infamous early Combines by Robert Rauschenberg come to mind, which incorporated household items, detritus and paint in a fragmentary, funny and fuck-you fashion.

The Known Universe, 2017, pigmented polymerized gypsum, epoxy, steel, cheesecloth, 198 x 133.5 x 53.5 cm.

Indeed, Weppler and Mahovsky’s project may be meant, in part, as an ironic and mocking critique of expressionism, while at the same time sincerely sharing in its exploration of existential experience. They employ reproductive technologies known for their descriptive accuracy (casting in gypsum) and yet obscure their plaster products to the extent that recognition and legibility become problematic, and the very concepts of communication and currency are brought into question. Who Goes There? offers further commonplace imagery—a table, a lamp, a vase with flowers—now charred and twisted, decimated by heat or other forces. But, here, material and process take on independent lives. The acidic addition of yellow fluorescent spray paint and a blue rectangle—referring to a mini blue monochrome painting or a smartphone screen—supplies a sardonic comment on how our devices will reboot after the apocalypse, maybe unencumbered by us.

Mountain consists of layers of cardboard, melded together with pigmented gypsum to compose a desk that seems to bear an enormous burden. The sculpture includes a veil of white material that appears to have been drizzled. This veil-like covering comes across as a levelling process, one intended, possibly, to bring all these elements and materials (cast and non-cast, abstract and literal) into the same semantic realm. This activity may again connote a sense of either sullying or consecration— or the acts of obscuring and/or anointing a body of material, with each cardboard piece representing a different work of art or page of a book, a corpus that is being prepared somehow for a new level of existence. So there may, in fact, be something spiritual about this coalescing ritual. As such, it recalls Louise Nevelson’s sculptural tableaux of the mid-1950s, when she assembled found furniture fragments and scrap timber, and then covered the composition with a single shade of white, black or gold. While Nevelson sought to paint worthless found material in a relatively focused and completely sincere manner—as a means to tap into mystical and unconscious processes—Weppler and Mahovsky’s work comes across more as an assemblage made up of individual parts. As the title suggests, this conglomeration can signify as a mountainous monument, but one that does not memorialize in a static or staid sense. Rather than a ghostly impression of furnishings in the vein of a Rachel Whiteread bookshelf, Mountain feels more like an active arena—a site of being and becoming—for ongoing rituals of casting and mark making that reflect (on) the here and now. Like the exhibition in general, this is a site that makes room for a remarkable range of experiences, from the dreaded to the absurd. ❚

“The Guest’s Shadow” was exhibited at Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto, from September 7 to October 14, 2017.

Dan Adler is an associate professor of modern and contemporary art at York University.