Taryn Simon

After reading Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays (Princeton University Press, 1957), I saw the world and its composite narratives, both grand and small, unfold around me in patterns of myth. This arrangement introduced an allegorical logic, which managed to somewhat neutralize the perceivable terror in randomness. However, as time passed and my mind splintered and weighed with the detritus of words we call facts, I lost the eye for myth and the world took on a more empirical, if chaotic, feel. Entering the “archive,” which is Taryn Simon’s “A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII” at MoMA, I was, chapter by chapter, cured of my blindness yet increased in my anxiety, and reminded again that the order in chaos is found in its repetition.

To find myself thinking of Northrop Frye upon visiting this exhibition is not accidental, nor is any aspect of the show, with its semiotic arrangement of image and text leading us to inevitably pessimistic conclusions regarding fate and its origins. “A Living Man Declared Dead” seems to support Frye’s belief that in literature (which essentially is how the exhibition reads, to the extent that it also has been published in book form by Mack), mythological structure always precedes content, and that it is “thought that flushes out the skeleton of myth.” Furthermore, he felt that because a structure exists, it should be possible to scientifically investigate literature in order to understand its laws. I would posit that mythological structure and scientific investigation are the major underpinnings of this project, as Simon systematically researches, collects and orders family bloodlines, which align themselves in a code of repeating archetypal episodes, appearing at once archaeological and premonitory. To say that “A Living Man Declared Dead” is about myth would be misleading, but it does establish a two-fold relationship with it. In using variations of mythoi, or archetypal narratives, Simon challenges a popular modern myth of Western liberalism that suggests human agency is equal despite the limits of nation, culture or religion, and that free will has dominion over circumstance. Each case study contributes to a cumulative momentum, but in perpetual descent, where concerns of survival trump those of self-actualization and living is a precarious state of being rather than becoming.

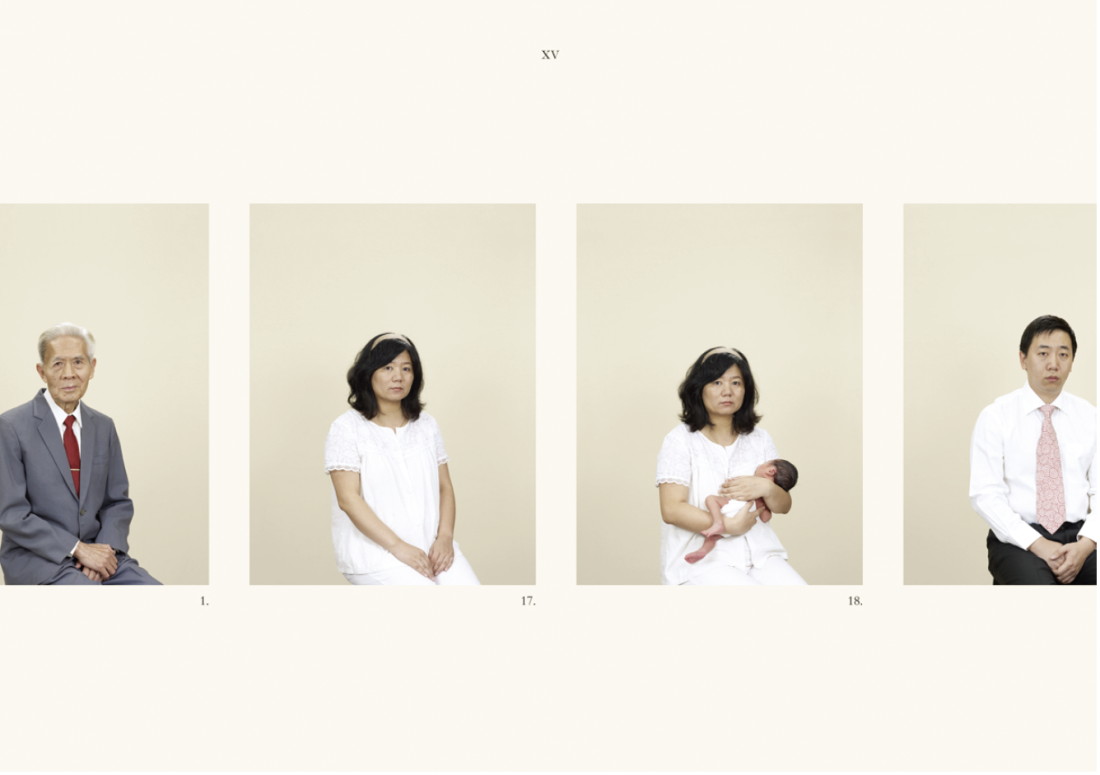

Taryn Simon, excerpt from chapter XV, “A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII”: 1, Su, Qijian, 19 Nov. 1926, Administrator (retired, Ministry of Railways), Beijing China; 17, Zhang, Jing, 27 July 1975, Homemaker, Qingdao, China; 18, Ma, Yucheng, 06 Sept. 2009, Qingdao, China; 19, Zhang, Qun, 27 Mar. 1979, Advertising designer, Beijing Gotwin Culture Communicate Limit Company, Beijing, China. © Taryn Simon. Images courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Taryn Simon is well-known as an unflinching registrar of the difficult or inaccessible, having catalogued an interior mythology in An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, 2007, and recorded the confiscated evidence of what she termed “a flattening of desire” in Contraband, 2010. In both, hints of the current project can be found: for example, at least two of the pieces in An American Index are grid-like arrangements of portraits linking subjects through blood or circumstance, similar to those found here. In Contraband, we see the homogenous presentation of a singular subject understood in a serial sense versus the grand narrative photographs of previous collections. Both these projects pair image and text, but in a manner less successful or reflexive than in the current application. And, as though the challenge of accessing and recording the off-limits was not enough, for this project Simon sought what she terms “an absolute index”—one that she could not curate or edit, which brought her to the idea of bloodlines.

“A Living Man Declared Dead” is composed of 18 chapters (nine of which are on display at MoMA) that trace various lineages of misfortune, collected from all parts of the globe. The “point persons,” which initiate a particular genealogy, include, for example, the living dead in India, a polygamous healer in Kenya, the first female hijacker and a plague of rabbits ravaging an island paradise. Each chapter consists of three components: on the left, one or more portrait panels of systematically ordered bloodlines; a centre text panel, which provides basic biographical details and outlines a corresponding narrative; and on the right, a footnote panel composed of photographs in a more abstract, intuitive arrangement. The portraits and text are both presented in a deadpan fashion—the poses are similar, the cream-coloured background the same, the gazes equally empty, the text formal and unsentimental. The footnote panel often includes ironical information that further twists the knife in tragedy, such as the slogan found on the wall of the history classroom in a Ukrainian orphanage with an abysmal adoption rate of one child per year, which reads: “Those who do not know their history are not worthy of their future.” Such details demonstrate Simon’s acute curatorial eye and her ability to craft a story, but also illustrate how circumstance may not only thwart desire, but mock it as well.

{medoa_2}

Through a repeating code of dialectics, Simon builds an unstable structure of human misery and tragedy, where interior will collides with external circumstance, absence jostles with presence and the past bleeds into the future. As well, history pushes against memory in the placement of the highly ordered portrait and text panels next to the abstract footnote panel. The involuntary call and response between fact and fiction that ensues from this positioning is uncomfortable, as we stand, for example, in front of a genealogy interrupted by genocide, where forensic evidence asserts the absence of family members. Part of the discomfort comes in the realization that ensnared as we are in the mass of stories, we may momentarily forget that the portrait subjects are not simply characters and the thematic variations in violence are more than literary tropes. Moreover, it is disturbing to consider as art objects the “matter-of-factly” presented documents of real-life tragedy, with portraits stripped of all narrative context, which do not directly read metaphorically or allegorically—it is, as Frye says, thought which makes it so.

This brings me to a final reflection from Anatomy of Criticism, which posits that tragedy and irony (along with romance and comedy) are the episodes that comprise the total myth quest, and certainly every narrative of “A Living Man Declared Dead” contains elements of the two former mythoi and some explicit or implicit thread of this theme. However, considering the chapters holistically, which is what the artist encourages, they form an epic that traces her own quest, partially Quixotic in ambition and partially Dantesque in trajectory. Propelled by more fortuitous circumstances, Simon continues a labyrinthine investigation into major and often uncomfortable questions regarding the human condition, and the possibility of individual purpose amidst collective chaos. Although she may not always succeed in answering these questions, she does assert that her purpose is in the asking. ❚

“Taryn Simon: A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters I–XVIII” was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, from May 2, 2012, to September 3, 2012.

Tracy Valcourt lives and writes in Montreal.