Seth Woodyard

In this workaday world of repetitive and droning day jobs, how does an artist balance the mundane aspects of daily life with the pursuit of a craft-based practice that strives for spiritual uplift? Winnipeg artist Seth Woodyard’s recent exhibition “Good Work” at aceartinc. wrestles with this and similar questions while demonstrating higher aspir–ations for craftsmanship through his three-pronged exploration of labour, artistry and religious practice. Woodyard, a recent graduate of the University of Manitoba School of Art, who majored in sculpture and painting, currently supports himself as a tradesman during the week, restoring ornamental plaster and taping drywall. Raised as a non-ethnic Mennonite, Woodyard now identifies with the tenets of the Anglican church. His personal outlook—which includes elements of his upbringing, day-to-day life and masculine identity—is the driving force behind much of his artwork. With “Good Work,” drawing on his skills and influences, Woodyard aims to bring together the sacred and profane through a hybrid multi-media installation. The result fills aceart’s main exhibition room with a sort of workshop- temple mimicking elements of ecclesiastical architecture and alluding to the abstracted form of a woman’s body. The installation is composed mainly of construction-grade materials: exposed two-by-fours, lath and plaster, drywall, ivory-coloured canvas, blue tarp, heavy-duty plastic sheeting and plastic mixing pails containing several hyssop plants, an herb known for its use in religious ritual. A form repeated throughout the exhibition is the vesica piscis, a consecrated shape created by the intersection of two circles which, according to Woodyard, represents the coming together of any number of binaries as well as an allusion to the vagina as a sacred site of desire and (re)birth.

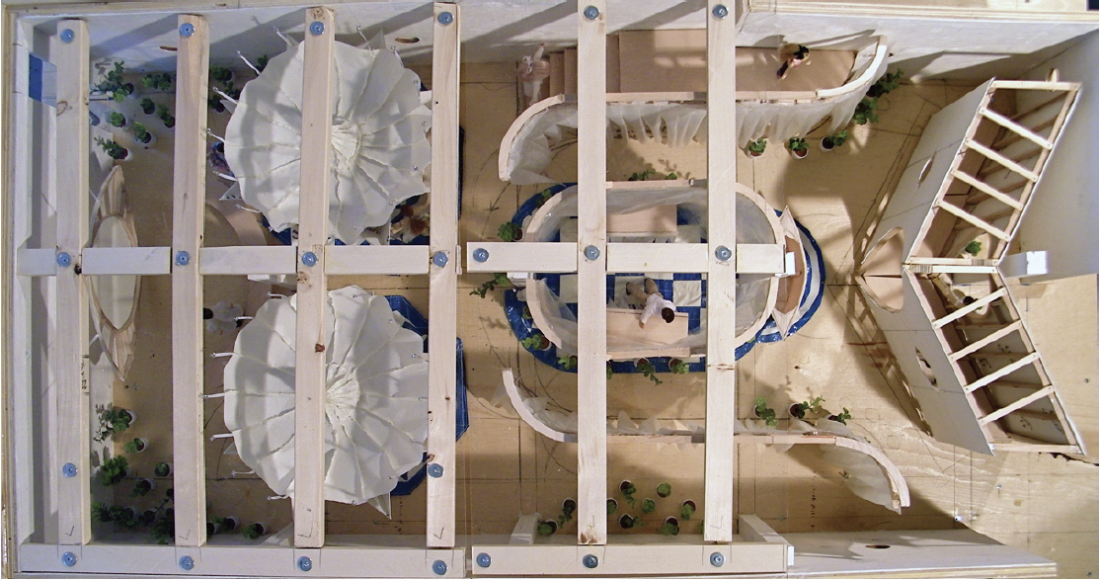

Seth Woodyard, Good Work, 2012, scale model of installation. Photograph: the artist. Images courtesy the artist and aceartinc.

Audiences enter the installation through the vaginal canal of a vesica piscis portal leading to various stations drawn from religious traditions: a fountain created from a vesica piscis-shaped bathtub; a nave leading to a workshop area where Woodyard laboured during gallery hours, casting a small army of salt-figure workers to be sacrificed in the fountain; a belvedere or balcony overlooking the entire installation, where audiences could pick up a detailed pamphlet compiled by Woodyard on the show; two octagonal gazebo structures with video monitors showing Woodyard participating in repetitive labour and, at the end of the exhibition space, a chancel with another video projected in the place of an altar. This video is a collaborative performance bet–ween Woodyard, bathing in the sanctuary of a church, while local band Alanadale (who also played at the opening reception of “Good Work” along with the all-male Riel Gentleman’s Choir) performs an original song about the doomed labours of Sisyphus. The video acts as the climax to a layered and nuanced exhibition touching not only on craftsmanship, art, work and religion, but also on issues of repetition, ritual, masculinity, the writings of Albert Camus and William Morris as well as the aforementioned myth of Sisyphus.

Seth Woodyard, Good Work, 2012, installation view at aceartinc., Winnipeg. Photograph: Karen Asher.

“Good Work” is nothing if not loaded with Woodyard’s near obsessive consideration of his broad subject matter, bringing it all together in a 25-page essay on display for viewers in aceart’s adjacent project room (presented alongside a scale maquette of the installation for viewers to get the “God’s-eye view,” as it were). The detail and forethought is certainly impressive for what is essentially the first solo exhibition of this young artist. While the content is open and approachable, Woodyard is clear in defining that the artwork (its highly gendered masculine language included) is grounded in his personal position, and that alone. It is the output of the artist’s own quest for cultural elevation, understanding of self and celebration of craftsmanship, as well as his ultimate striving for the greater good, from his perspective.

For a viewer, this highly informed and inquisitive personal devotion does have its limits of accessibility. At five months pregnant during my visit to “Good Work,” the installation’s allusion to a woman’s body resonated for me in ways likely beyond Woodyard’s struggle to circle in on what it means to be a good man working today. The vagina as sacred site of desire, the workshop as womb and the altar space as the brain with a video looping a naked man cleansing himself, all stand in contrast to my personal relationship with the gestating female body. For women, queer audiences, non-believers and others, Woodyard’s perspective as the heterosexual Christian male recalls something stifling from art’s past that is far from edifying. However, Woodyard dares to interrogate these channels, and for a first exhibition he deserves recognition for his demonstrated craftsmanship, attention to detail and sincere grappling with the significance of what it means to do “good work.” ❚

“Good Work” was exhibited at aceartinc., Winnipeg, from June 8 to July 13, 2012.

Jenny Western is a curator, writer and educator living in Winnipeg.