Sanaz Mazinani

Artist and photographer Sanaz Mazinani’s burgeoning, intensifying pursuit and examination of the instability and resulting volatility of photographic materials extractable from popular sources—chiefly the Internet—has carried her a long way from the first work I knew of hers: the book-cover photographs (“Bibliotheca”) she exhibited at Toronto’s Stephen Bulger Gallery in 2005.

The “Bibliotheca” photographs were large-scale, isolated images of highly used books, often dog-eared, usually creased, worn and clearly much thumbed. What was most interesting about them were the secret histories each seemed to accumulate. Somehow, their distressed condition now rendered them neither picturesque nor sentimental but, rather, amplified a silence inherent in each of them—a withholding of the very narrative with which you felt each of them was, by now, richly imbued. A similar but densified kind of muteness is everywhere felt in the politically searching, historically accomplished, technically remarkable digital collages the artist has been making since 2008, in San Francisco.

Born in Tehran in 1978, Mazinani immigrated to Canada when she was 11 years old, bringing with her a richly inexhaustible, inherited understanding of the power and meaning of pattern. As she notes in a recent video (you can see it at www.sanazmazinani.net), “in Islamic art, ornamentation is the art of transformation and comes out of the Islamic preoccupation with the transitory nature of being.”

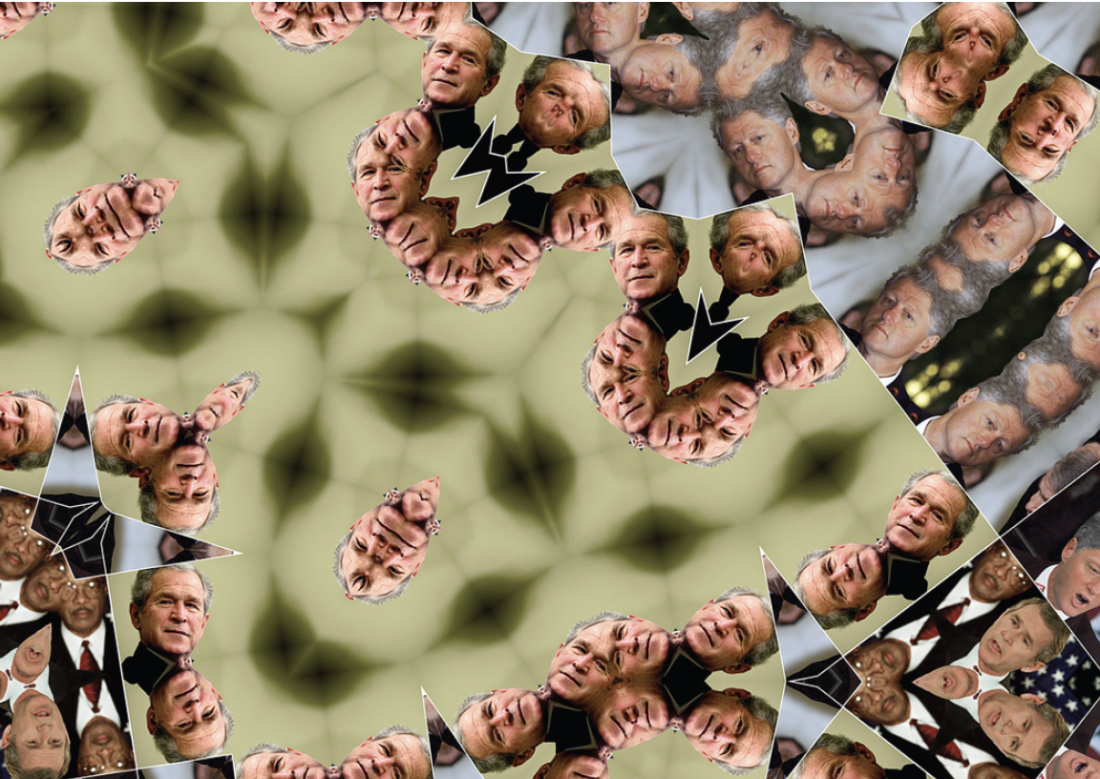

Given the nature of the fleeting, almost unexaminable but nevertheless potently loaded photo-images from the Internet—of which her dizzying, kaleidoscopic collages are composed, photos with their own sense of the “transitory nature of being”—there is an almost wicked logic in bringing together that dangerous fluidity and the disturbing evanescence of mass-media images of war and conflict with the solid, deeply satisfying spatial and chromatic logic of Islamic-derived patterning.

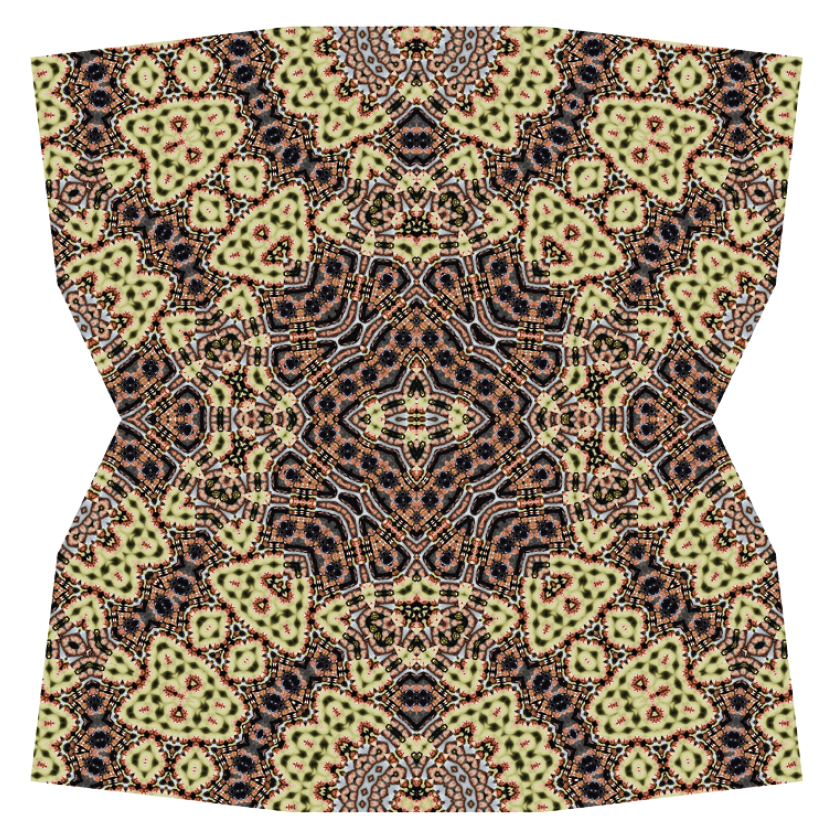

Sanaz Mazinani, Living With War, 2011, archival pigment prints, edition of 7, set of four, 21.25 x 21”, assembled 42 x 44.5 x 6”, mounted to dibond. Courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto.

That the two feeds of information should fuse so potently, even exhilaratingly, despite the troubling nature of the political photographic components, into such vibrant, mosaic-like wholes is a great tribute to the artist’s conceptual inventiveness and procedural tenacity. Not the least remarkable quality of Mazinani’s photo-objects is the way both the photos and the fields of patterning are made to become, in the end, entirely interdependent. And this is partly a matter of viewer focal-length. Looked at up close, the works are clearly an outwash of photographs held in place by a matrix of design-will. Looked at from across the room, however, the works become eccentrically-shaped fields of pattern—design-rapture, essentially unencumbered by the socio-political. As San Francisco-based writer and artist Jeremiah Barber puts it in a stimulating essay, “Smoke and Mirrors,” in Unfolding Images, 2012, a catalogue recently published by the Bulger Gallery Press, the unique forms of Mazinani’s collages “are innocent. One unfolds like a paper airplane, another like a winter snowflake with just one careful cut. Mounted on panels they bow inwards at the edges, so that approaching the pattern fills your plane of vision rapidly…”

Are you going to be inescapably drawn forward into the political content of the works, or simply rebuffed into the apparent safe haven of the delectable, accumulated design-energies—that, in the end, provide the site for the pivotal yes-no, both-and performative nature of the pieces? The best place for a viewer to be, obviously, is somewhere in the middle, from which vantage-point the two disciplines that order the works can both be responsibly negotiated.

Mazinani’s “Frames of the Visible” works, of which there were six in the Bulger show, look exhausting to the point of being impossible to make, but she proclaims it to be otherwise. She says she begins with a single Internet photographic image, sometimes two of them, then makes copies (two become four become eight, and so on), decides on the pattern they will make—or be incorporated into—and then goes on cutting and pasting electronically, mirroring and replicating them until she has Photoshopped herself a giant new work. Usually the images, which she insists be seamlessly juxtaposed, come together at angles, providing a sort of structural pun by which the sliced and reassembled images inevitably work their way towards, becoming angles of interpretation.

While it is clear that development of the overall pattern of each work is continuous in mood and tone with the photo images within it, Mazinani’s selection of images, and therefore, ultimately, of the morphology of her pattern-mosaics, ranges widely from mordant bemusement (Together We Are, 2011) through skepticism (The In-between, 2011), past spurious metaphysical inquiry (Living With War, 2011, a mock-heroic investigation into presidential hair colour and personal longevity), to lament and pained resignation (Land of the Giants, 2011). Her choice of photo-material is always canny, frequently witty, though it is a wit usually laced with disbelief and dismay, and unfailingly probing.

Sanaz Mazinani, Living With War, 2011, archival pigment prints, edition of 7, set of four, 21.25 x 21”, assembled 42 x 44.5 x 6”, mounted to dibond. Courtesy Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto.

The coming together in Mazinani’s patternworks of both urgency and poignancy in the doublings, and dizzying proliferations and accumulations of her photo-images, is based on a fierce procedural tact: in Land of the Giants, for example, the artist’s fascination with an Internet image of a woman in front of a green flag, armed with a semi-automatic rifle (“the seventh female suicide bomber in Gaza”), proclaiming her body to be her only tool, is suddenly seen in the work—given the way she is multiplied by herself—as a horrifying media stutter, within which the desperation of this mother-and-militant brims, oceanically, into a compassionate parody of mass-media’s thin, patchwork-blanket-coverage of her plight.

In Together We Are, by contrast, another female suicide bomber—an image, Mazinani reminds me, employed in propaganda pieces by both Palestinian and Afghan sources at the same time—is paired, this time, with a photo of Paris Hilton unbuttoning and therefore unburdening herself: two women armed with two different kinds of urgent disclosure. “As media icons,” Mazinani tells me, “both women had a lot in common.”

Revelation does not follow upon revelation. Maybe that’s what the patterning is really for: to give the viewer time, in the interstices between photos, to think things over.

How can we trust what we see? How do we begin to see what we trust? How do we wake up from the numbing proliferation of info-laden media images, all of them trying for our attention or, contrariwise, often hoping to elude it? If you are Sanaz Mazinani, you play with the problem, picking, choosing and introducing bits of urgency into the apparently benign, history-rich host-matrix of colour and pattern that is the Islamic ornamentation she grew up with—an ornamentation that proclaims in its essence “the transitory nature of being.” ❚

“Sanaz Mazinani: Frames of the Visible” was exhibited at the Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto, from May 5 to June 9, 2012.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives near Toronto.