“Earth Art 2012”

On a cool, cloudy October day, I walk through Vancouver’s VanDusen Botanical Garden, searching out evidence of the earth art that was installed in late July and early August. My first viewing of these works took place under a hot summer sun, amid an air of resourcefulness and enthusiasm. Montreal-based writer and curator John K Grande had assembled a distinguished group of artists—Chris Booth from New Zealand, Nicole Dextras from Vancouver, Nils-Udo from Germany, Urs-P Twellmann from Switzerland and Michael Dennis from Denman Island—to respond to the site and the natural materials at hand. And to remind us, Grande told me, “that we are part of nature, not separate from it.” The resulting environmental works ranged widely, from heroic to delicate, interventionist to integrative, and permanent to ephemeral. Record-setting days of unbroken sunshine seemed to applaud the exhibition. Now, however, amid fallen leaves and dying flowers, with the artists long gone from the place, an elegiac air prevails.

Or perhaps I’m being overly dramatic. Even this late in the season, the gardens are filled with signs of enduring life. Japanese maples display their leafy capes of gold, scarlet and burgundy; mountain ash bear heavy clusters of cadmium red berries; and the frankly named hardy cyclamen spread small white flowers around the foot of a weeping giant sequoia. In the perennial gardens a lone, sluggish bee sips at the golden centre of a purple dahlia, then carefully wipes pollen off its face with its forelegs. Nearby, on a patch of lawn, a phalanx of dresses made out of organic materials and mounted on wooden stands is slowly, gorgeously decomposing.

Urs-P Twellmann, installation view of Zipper, at “Earth Art 2012,” at Van Dusen Botanical Garden, Vancouver, wood, approx. 35’. Courtesy the artist.

Created by Nicole Dextras, who has long worked with ephemeral materials such as leaves, flowers, grasses, vines and even ice, “The Little Green Dress Projekt” speaks to one of her recurring themes, which is the way fashion and the clothing industry hugely and negatively affect the natural environment. In their inventiveness and visual appeal, the dresses also evoke what the artist calls “the complex human need for adornment.” Each of the dresses was composed of locally sourced and renewable organic matter, from berries, rushes and fern fronds to thistles, mosses, seedpods and seaweed. And each dress was named and custom-designed for the women—friends and colleagues of the artist who participated in the project by donating materials and filling out a questionnaire about their attitudes towards eco fashion. The artist’s progress through August—a dress a day for 28 days—was marked not only by displaying the newly constructed works in the gardens alongside those created previously, but also by photographs posted on her blogsite (www.littlegreendresses.wordpress.com). Fresh, lustrous and colourful when they were first made, the dresses now range across dying shades of brown and grey, their components collapsing, shrinking and falling away in a manner that seems not only to trace the cycle of the seasons but also to mourn the embattled natural world. Be aware, these increasingly ghostly forms tell us.

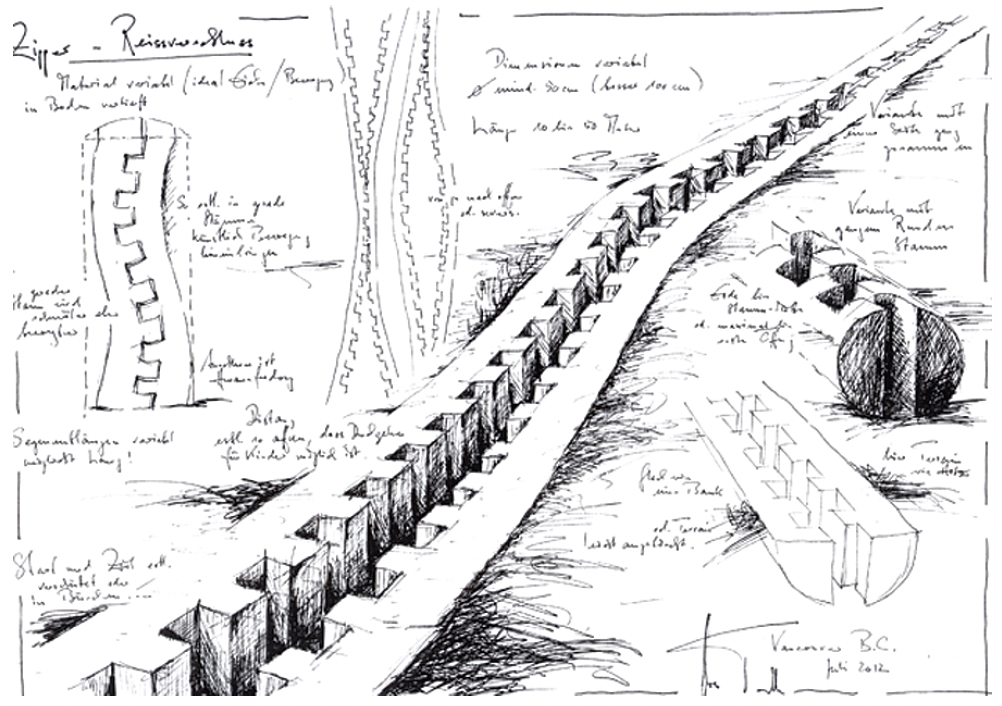

Not far away, Urs-P Twellmann has embedded a giant wooden zipper within the lush green grass of the Great Lawn. Characteristically, he works with the unlikely tool of a chainsaw to create poetic sculptures and installations out of wood he finds on his chosen site. In Vancouver, he sawed the components of the 25-metre-long Zipper from a couple of Douglas fir trees that had blown down during a windstorm in the area. Progressing up a hillside from “open” to “closed,” Twellmann’s work is a delight to encounter. Its elements of novelty and gigantism stimulate a few different metaphors, from the folkloric to the scientific. Zipper provokes our thinking about archetypes of the chthonic and our dependence upon and still-limited understanding of the deep, dark ground on which our human lives are built, the ground from which we daily extract sustenance, fuel and, in some cases, fortunes. On the earthquake-prone West Coast, Zipper resonates with a further theme, that of the earth opening up before us. And although a cautionary element may not be what the artist intended, it is possible to segue here into concern about recent invasive and exploitative practices of the coal and petroleum industries—fracking and carbon capture—whose ultimate biological and geological impacts, deep below the Earth’s surface, are still unknown.

Urs-P Twellmann, Zipper, 2012, project sketch.

Chris Booth installed his monumental work in the far northwest corner of the garden near a stand of Douglas fir trees and a pair of Gitksan totem poles, one carved by Earl and Brian Muldoe, the other by Arthur Sterritt. As I approached Booth’s piece, I had the sense of entering a place sacred to Stone Age peoples, a site monumental in its assertion of human aspiration, yet intimate in its regard for the tiniest workings of the natural world. Set within a low, circular, stone wall is a concentric arrangement of rough-hewn granite slabs, standing upright or gently tilted outwards, and supported by heaps of cut-up logs and other plant matter. Newly rooted at the centre of the whole arrangement is a cedar sapling.

Again working with materials found and reclaimed on the site or gleaned from other park projects (the granite was left over from a recent reconstruction of Vancouver’s seawall), Chris Booth has created an unlikely shrine to…fungi. The installation’s components are assembled in such a way that over a period of 30 years, the organic elements will decompose, and the standing stone slabs will slowly descend and open up, ultimately arranging themselves like the petals of an enormous flower around what should then be a towering evergreen. When I talked with Chris Booth last summer, he was enthusiastic about mycorrhizae, the fungi that cause wood to rot and that play an incalculable role in the cycle of life, returning nutrients to the soil, out of which new forms will emerge. The subtext to his tribute is that we should be aware of the impact of climate change on these unseen organisms.

This is a sobering place to sit and contemplate our past, present and future relations with nature. And to wonder who will be here to see the fully realized stone flower of Booth’s imagining. Somewhere, unseen, a great blue heron is broadcasting its presence through a series of loud prehistoric croaks, a sound, I imagine, that pterodactyls must once have made. A couple of crows fly by, cawing and complaining, readying themselves for their late-afternoon migration along with thousands of their fellows, to their winter roosting place in distant Burnaby. Drizzle descends on my reverie and it’s time to go home. ❚

“Earth Art 2012” was exhibited at VanDusen Botanical Garden, Vancouver, from August 2 to September 30, 2012.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and Contributing Editor to Border Crossings.