Reverence Points

The Art and Mind of Gedi Sibony

A piece of used carpeting measuring 100 by 74 inches, with white paint or primer on the surface, doesn’t add up to much unless you read the marks and find there a representation of the Annunciation in one of its many iterations. Think of 14th- and 15th-century paintings by Fra Angelico, Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci. Two figures in profile, the angel, often on the left, carrying the divine message, and on the right, the humbled, astonished recipient, seated or kneeling. Separating them, there is always a space to carry the import, the meaning, to designate the distance between the divine and the mortal, now drawn proximate through the fateful event that must be realized—but not ever touching. This is Gedi Sibony’s work, In the Great Flare Up, 2007, his Annunciation painting. In talking about Annunciation paintings with Border Crossings, he calls our attention to what he describes as the short three-dimensional extensions of the space he sees when he finds the paintings in churches, for example. I’m suggesting that short, charged three-dimensional space is sculptural.

He says he sees the paintings and that space as a “point of focus that was so well-transitioned … you could feather out that point of concentration in all directions.” Now it has volume, is what I am understanding. Gedi Sibony goes on, “But the point is the empty space between the two … isn’t filled with words—it’s not filled with anything—in the middle of all that energy.” He says that what he is doing with his work is “concentrically framing with a symbolic order and ultimately it’s toward the transference of that unnameable emptiness.”

Gedi Sibony, The King and the Corpse, 2018, portable porcelain-steel façade, steel, bolts, screws, wood, c-clamps, dimensions variable. Photo: Elisabeth Berstein. All images courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York.

I’m thinking here that his artmaking—his work in the studio and in galleries—is his framing with a symbolic order through making, and then installing, which is toward the transference of that unnameable emptiness, that annunciatory, charged, empty space. What he is after is making manifest the presence of that absence. A spiritual sensibility, developed as a child, made him receptive and perhaps inclined to recreate a setting, a theatre of spiritual possibility.

Childhood is an ever-replenishing source, a suspended place that shapes us and to which we return often, dipping like swallows to sip and restore ourselves. Gedi Sibony speaks with pride, a word he used with intention twice when responding to our question about his choice of materials. His interest in not producing things, in not using resources, in not spending money came directly from his childhood and the ethics of his upbringing. His father, one of eight children, grew up in Tangier, in a single room where everything, as sparse as it was, was shared. When his father emigrated to New York, his work was renovating apartments. Anything useful that he removed he brought home to their apartment to be used again. He was proud of what he was able to do; his resourcefulness served his family well, and in turn, Gedi said he was proud, liked the idea. If you visit his filled studio and when you look at his work, you see evidence of his fine lineage.

There would have been many formational elements in his childhood, but the one that recurs through this conversation, and seems most evident, is spirituality. The desired state of reverence was queried and the answer: “I think as a child I achieved reverence, out-of-body experience, in a religious setting—group chanting and praying and fasting.” He adds surfing as a subsequent adult occasion for an out-of-body experience. He also achieves this in rare moments in the studio, he says.

Art is likely, usually material, some material; it manifests itself, for the most part, in some physical way even when it is largely conceptual. Even when minimalist or spare, there is sufficient body to leave a trace. So it is interesting, very interesting to look at and think about Gedi Sibony’s work, where what is not there is as resonant as what you can measure or weigh or rub or move with an exhalation of breath. Because in his work it’s the spaces between, it’s the linking ellipses, it’s the um while you are thinking. It’s the space before and after that you know must have been there and continues to be there in that same way. It is implied space, and you are implicated in its having been there at some point and your being aware of such. It is anomalous: ethereal and sculptural. Sculptural, which suggests volume, a ground or base or platform even if hanging. Ethereal like ether, a gas, and transitory.

Here is William Carlos Williams with his epic poem Paterson from 1927 and his saying, “No ideas but in things,” to be economical with words, the conviction that only things can create visual images for us. I apply this to what happens in the pared works and installations of Gedi Sibony—that space he gives and leaves for sensibility, thought and reverence. Reverence and a state of immanence and the artist speaking about entering a gallery and crossing a threshold. He identifies that transit as “an opportunity to immediately wash my memory of whatever I was doing before,” and he goes on, extending that moment to others, “then I get to keep people in a state where they don’t have to remember things again until they leave.”

Studio, Gedi Sibony, November 2019. Photo: Gedi Sibony.

This implies, for me, a sanctuary, and I think of works like I Stay Joined/We Approve, 1991–2007, where three thin pipes suspended over a free-standing door make an altar and sunlight streams in. Where We Approve, 2007, and Untitled, 2007, installed in the same space, collaborate with an angled architectural ceiling element and the light through a narrow rectangle of a window becomes a chapel. Or Ultimately Even This Will Disappear, 2007, where a piece of carpet with its two far corners lightly lifted like eyebrows asking a question, a Plexiglas frame standing and a spotlight trained in a small, soft flare on the floor are a space for soulful contemplation. Transcendence, out of body, a state of reverie. Being aware of the simple gesture of crossing a threshold: one foot over, one foot back in an hypnotic prayer-like sway.

The provisional quality of these physically spare, evocatively rich works calls forth a sense of poignancy, so tentative but with a productive bifurcation—his self-identified knowing body and the moving-fasterthan- thinking body, both acting. Tentative in the sense of a gentle delicacy or discretion and always leaving open the possibility of something else—a veiled delicacy, that is, with the delicacy of a veil, and wrists and ankles available to the wind.

Robert Enright said, “You know, you are a cardboard and carpet mystic. I mean that as a compliment.” Gedi Sibony said, “You are a great interviewer.” (And then they embraced.)

This interview is a composite of two separate conversations. The first followed Gedi Sibony’s lecture for “Dialogues in Art,” a collaboration between Border Crossings and the School of Art at the University of Manitoba, in Winnipeg, on November 21, 2019; and the second was a telephone conversation to his studio on December 30, 2019.

Border Crossings: Did you at any point make the determination that you wanted to be an artist and if you did, when did it happen?

Gedi Sibony: It happened when I was living in San Francisco trying to be an artist and I found the Bruce Nauman catalogue raisonné. I hadn’t had much exposure to his work, but as soon as I opened the book I saw that art could carry everything. Before that I thought I wanted to be an artist, but I didn’t think that it could have everything in it that I wanted to say, which was a combination of so many blurry things. But everything changed when I knew that it was doable in that form and in no other. On the first page of the catalogue raisonné there is an early piece that is a kind of painting, it’s very vertical and curves a little at the top, and inside is a shape, a sort of three-dimensional side of a cube, that mimics the shape of the canvas. As a kid I loved going to museums and loved the way that culture and civilizations were presented architecturally. So I was connected to looking at paintings, but I guess with that work there was a vulnerability, an encapsulation of some degree of humanness that I was better able to see because it was abstracted. Not cleaned, not pure. It felt like all the theorizing around art from my academic background didn’t apply. It was much simpler than that. Difficult but also simple. This happened a couple of years after I had graduated from college and before I went back to Columbia. I was still sorting everything out.

I Stay Joined/We Approve, 1991/2007, carpet, door, pipes, 39.8 x 118.5 inches (carpet), 20.8 x 86.6 x 1.8 inches (door), 82.6 x 74.8 x 82.6 inches (pipes). Installation view, “If Surrounded by Foxes,” 2007, Kunst

Was the recognition of what Nauman had done generative for you when you went to Columbia for your MFA? Did you set about to apply some of the knowledge you had obtained in the Naumanesque experience?

No, I was continuing to be a little bit in the dark in my own investigations. I just knew that art could be dynamic and deep enough that whatever it was that I needed to say could find a form. It did take years after that to find a proper form. But as I think about it, I did go through a period of time where I was doing performances and videos of myself doing performances. I probably was trying to be Nauman.

Your work is materially so rich that what I want to do is get inside your creative process to figure out how you actually make the things you make and why they work so well.

I think the problem is that it takes a lot of time. Not so much gets done, but it takes a lot of trial and error and there is a lot of failure. All that’s left is the part that distinguishes the failures from the successes, and what determines that? I mean, people tend to agree on the better things, so there is something semi-common about the recognition of that process. My process is scattershot, and if I were to think about what I am capturing, I would recognize that there is a preliminary stage when the objects are offering a state of future culmination. It is a relationship between things that offer interpretations that don’t land comfortably. It’s like putting words together until there is nothing opposite; they’re in a state where they don’t have an opposite. Maybe that’s an enriching place; maybe that’s an accurate depiction.

You name your paper on Nauman “Against Opposites.” You’re the opposite of a Cartesian; you’re always in the slipstream between things, where one thing becomes another. Is your job as an artist, then, to find those connections between things, to elevate the quotidian to something we would call art? What makes your work artful as opposed to that of a guy who gathers the throwaways of industrial America?

That’s a great question. I mean, what is the difference? Is it the language that makes it different? Maybe because I want something out of it beyond the facts of what it is or how it got there.

Your artmaking process seems to be one of being in the studio where you’re discovering the imminent possibility, but then comes the question of what happens to it when it is put into another space, like a gallery. Does it become a different work or is it evidence of the ongoing refinement that made it in the first place?

Originally, I felt that every time I went into a gallery, I crossed some threshold, and it was an opportunity to immediately wash my memory of whatever I was doing before. If I do that, then I get to keep people in a state where they don’t have to remember things again until they leave.

You said in an earlier interview that in this society you are “forcefully removed from reverence.” So is that state where you want to be and is art the way you might possibly get there? It’s almost a question about an old-fashioned spirituality. Removed from reverence by advertising, tricked out of a daydream state by a frantic state of desire.

The Middle of the World, 2008, vertical blinds, 36 x 89.5 x 5 centimetres. Photo: Gil Blank.

I think as a child I achieved reverence, out-of-body experience, in a religious setting—group chanting and praying and fasting, and later while surfing, particularly in conditions where it’s hard to see; consciousness splits away from the physical body to an outside perspective. So to have those experiences and then to enter an academic setting where we’re told unmediated experience is impossible…. But it is a positive state, achievable during rare moments in the studio. In terms of art, music, literature and poetry, and in theatre, I think something else happens. You can relate to the human condition as it’s being described abstractly, or through relationships, and you become hyper-aware. In both the out-of-body experience and the hyper-aware experience, time slows way down or the brain opens way up, or something, but they are very different. In hyper-awareness, you are your struggle and you see that others are, too, and you’re glad about it. In out-of-body, none of that matters. You just can’t believe that your body can keep doing something while you fly away. I don’t know what the formula is to activate that, but some things help visually: the incorporation of visual relationships into space, of architecture into the pictorial, and also integrating them into the sculptural. That has been done for thousands of years because there are ways to do it that have effects. There is probably some science to it, but my process is intuitive.

One of the ironies is that the artist is in the studio alone and negotiates time and space without anyone else around. There is no communal chanting and praying. Is one of the reasons why exhibiting is important to you because the gallery experience opens up the possibility of finding that lost reverence?

Those are two different things. In the studio alone without anyone watching, the hope is that anything can or can’t happen. Then there is a totally separate part, the editing and organization into a show. And that part depends on the encounter. Or it depends on an anticipation of the encounter.

Do you think that’s one of the reasons why your sculptures seem like imaginary people inside the spaces in which you place them? In your work there tends to be a drift towards the anthropomorphic. It’s as if you have the urge to somehow embody the material you use in a personality, a character that becomes human.

I notice that all the time, a quality that is a character. Getting something to stand up without a clear plan. Even if it’s closer to furniture, to architecture. I guess I’m responding to the presentative aspect of objects. Being greeted by the things presenting themselves doesn’t feel like being accompanied by other people, but it does feel like something is happening. So I can go to my studio because something is happening there. I mean, this is the last straw in terms of real, accompanied activity.

I agree that your work can touch on furniture and architecture and the anthropomorphic, but what interests me is whether the material is telling you what it wants to be, or is that you playing a subtle Svengali and shaping the material to have a certain presence? It’s a question of how much agency you have in the process.

Set Into Motion, 2010, wood, screws, paint, 106 x 176 x 36.5 inches. Photo: John Berens.

Well, I want all of the agency and none of the agency but not some of it. With the frames and then the trailer pieces, I could change nothing. The artwork was already done. Then I had to go get it, cut it out, hang it on the wall. The paintings, too. I had no say in designing the space, the curtain or the table, but then once it’s mine, I can take out the bottles and fruit or whatever. Then I want to make a good table to work on the paintings that I can move around and the table becomes a sculpture. In a way that’s no agency to all agency in one moment. I was making a table, and then made a decision. There are greyer areas, too, and sometimes that process leads to something. But that’s the quagmire of some agency.

You have said that you realized you’ve become really good at certain moves. Am I sensing in that recognition a nervousness about being too good? Can you know too much about the moves you are making and does that remove the risk you feel is necessary to make art?

There are only so many moves you can make to avoid yourself and once you’ve made them all, you start to avoid yourself again. Then you have to fight off the voice that is saying, “You know you’re trying to avoid yourself again,” and it’s kind of up for grabs. You can beat it sometimes.

And sometimes it beats you?

Yeah, sometimes it beats you right there in your tracks.

Can you always put yourself in risky situations? Is it even possible to do that?

I don’t know, but risk doesn’t seem as exciting as it used to. There’s a little bit of delusion with risk taking, with extreme risk taking. But the thing is, if the stakes are low, you can experiment and if you pull it off, then the rewards are high. But I don’t know if the draw of risk taking is as appealing as the draw of the compelling thing, right now.

Are you talking about personal risk or risk in a large cultural context? Is it wisdom or fatigue that determines that risk isn’t the same issue it was when you felt that an engagement with it was absolutely necessary?

Well, it totally comes from the context. As a young artist I knew I was right, and I wasn’t having exhibition opportunities and I was bucking the system and generating energies from being against it. Then you get pulled into the system and you think, I was just against the system and now I’m accepting it, and then you have to ask: What are you against now? My last show, “The King and the Corpse,” centred on a White Castle restaurant building facade being rebuilt inside the gallery. Maybe that was the biggest risk in the sense that it cost money and all the other things that I have done have basically been free. It cost labour to put that up. Maybe more than a risk, it was the challenge of seeing what the castle would look like inside the cube.

When you talk about building a vertical piece and you keep adding another piece of wood to the point where it could fall over, I think of what Lucio Fontana was doing with his cut paintings. One more inch in either direction and the painting collapses. That is real risk.

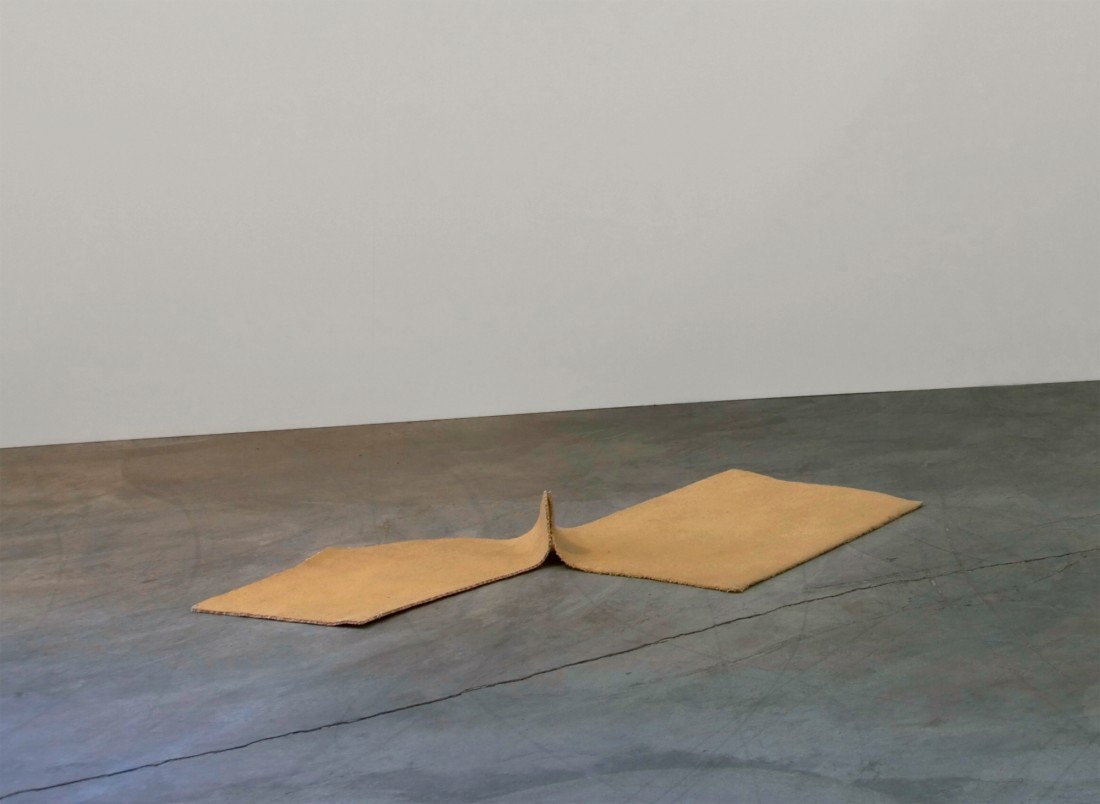

Kissing Carpets, 2005, carpet, 7 x 50 x 54 inches.

I’m so happy you brought up the example of Fontana because I’ve always looked at those cuts and thought, how do you keep the structure so perfectly; how did the cuts only spread this much? If it was more of a cut than I thought would be acceptable—only that much of a departure from the middle—would it work? In other words, there is only one way that it is going to work, and if the cut is a little bit longer than you think it should be to work, then it creates a feeling like: How is this working? So there is no too small; everything fails if it is overbuilt or overstable because it doesn’t enter the space where there is that feeling of something happening that shouldn’t quite be working like that. Maybe it is putting me on some sort of alert to not breathe too hard or change my relationship to it.

Of course, we didn’t get to see the Fontanas that didn’t work, anymore than we get to see your vertical sculptures that are overbuilt and collapse. The proof that they worked is that they’re being shown in a gallery. There probably were a number that weren’t successful.

Clunky ones. Clunky, too clunky, too clunky. And then the falling over, falling over, falling over. They fall over when they get shown sometimes, too.

…to continue reading the interview with Gedi Sibony, order a copy of Issue #153 here, or SUBSCRIBE today!