“Residency in RMB City”

The first time I checked out the online community of Second Life, where users interact via 3d avatars, I tried something I would never do if I were a flesh-and-blood visitor to an unknown place: look for the X-rated entertainment. Plugging “xxx” into the site’s search engine, I teleported to one of SL’s many sex clubs. Seeking out the curious spectacle of avatars having sex seemed to me the point of the exercise. What else was there to do? To the uninitiated, Second Life can be a rather lonely place. You can traipse about for ages and never meet another soul. Your avatar might be able to fly, traversing sparkly digital oceans, but this doesn’t help all that much.

A couple years later, I visited Second Life again, this time with a more “legitimate” destination. I was going to RMB City, a project of the Beijing-based artist Cao Fei. Still, my experience was much the same. Where is everybody? I am suffering from a disjunction between the real and the virtual, a dynamic Cao Fei had explicitly set out to explore. But if my navigations through the world of Second Life are cumbersome and alienating, it’s because I have a sub-par computer. It’s an issue of processing speed. Inadvertently, perhaps, Cao Fei’s ambitions in Second Life provide a metaphor for the looming dilemma faced by the West. We are lagging behind but lack the drive needed to overcome this predicament.

Yam Lau, Princess Iron Fan, Promenade in Second Life (sunset version), 2010, digital animation. Courtesy Gendai Gallery, Toronto, and Second Life.

Disjunctions between the real and virtual worlds, often unintended, also dominate the “Residency in RMB City” project. Because it is located in the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in the Toronto suburb of Don Mills, the Gendai Gallery is somewhat hard to get to. With this exhibition, Gendai curator Yan Wu puts the venue’s peripheral status to good conceptual use, proposing a show that can be, in part, accessed by computer. Working with the artists Adrian Blackwell, Yam Lau and the collaborative duo of Judith Doyle and Fei Jun (known as GestureCloud), Wu created an exhibition that combined a gallery presentation with digital artworks created for Cao Fei’s Second Life property.

Made up of an amalgamation of references to Chinese architecture, RMB City features the Herzog and de Meuron Bird’s Nest along with shiny skyscrapers, motorways and sidewalks, warrens of small shops selling take-out food and the like, all of it organized around the central structure of the Forbidden City, Beijing’s Imperial Palace, dating from the Ming Dynasty. Although Cao Fei promoted her project as a platform for artist collaboration, miscommunications meant that Wu found her initial proposal to create an artist residency in RMB City rejected by the artist. Further communications remedied the situation; as of press time, the artists are soon to begin moving their projects to the Second Life location. In recognition of the changed status of the project, this second phase will now be termed “Intervention into RMB City.” A publication about the project, called From Residency to Intervention, will be published in the spring.

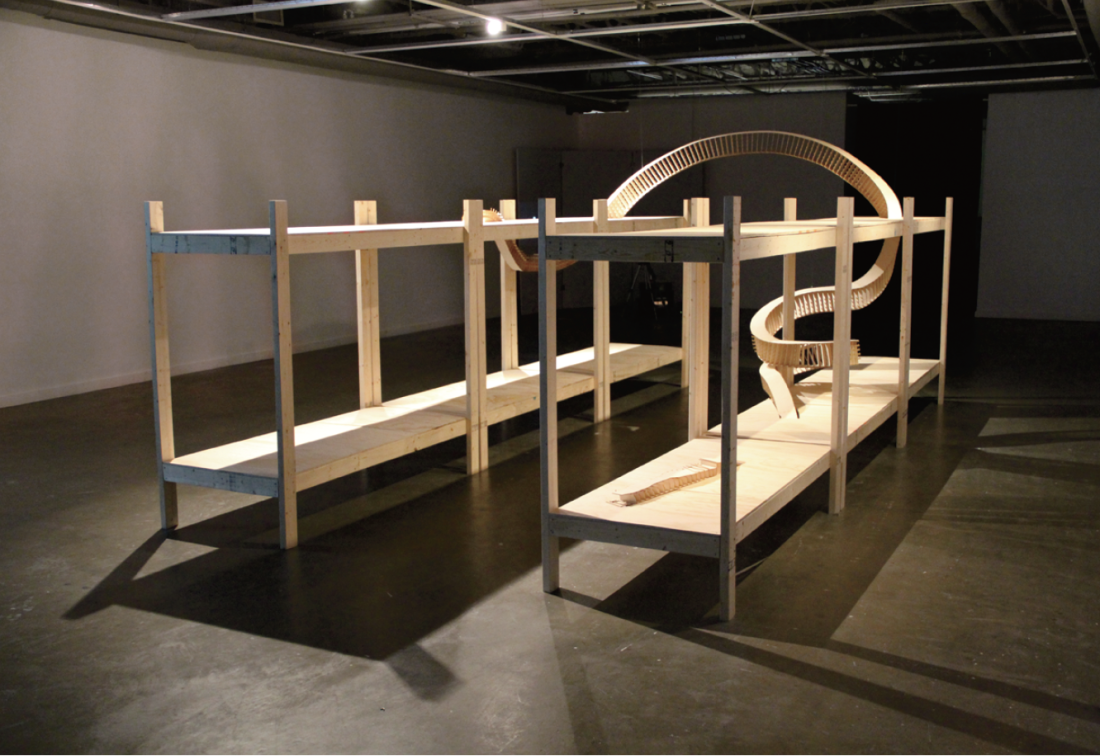

In the Gendai gallery, Blackwell presented Lóng Sùshè (Dormitory), 2010, a plywood maquette of a workers’ dormitory proposed for RMB City. Trained as an architect, Blackwell has lived in China, teaching architecture there at an off-site campus of U of T. With Lóng Sùshè he provides infrastructural context for Cao Fei’s metropolitan fantasy. An interest in sculpture as a platform for public discourse has been the long-term focus of Blackwell’s practice. Referring to an actual dormitory in the industrial region of Shenzen, one that is continually being built in an effort to meet the growing demand for workers’ housing, Lóng Sùshè helps to clarify certain questions that will emerge along with China’s growing economic dominance. What kind of public will China’s new global order create? How easily do traditions of the West translate, and are they even relevant? The notion of a public sphere is among the highest ideals of a functioning democracy, but it’s not clear how it will figure in a country that has little in the way of democratic traditions as they are known in the West.

Adrian Blackwell, Lóng Sùshè (Dormitory), 2010, lumber and plywood, 5.4 x 2.7 x 2.4 m. Courtesy Gendai Gallery, Toronto.

Writing about the legion of workers that power the engine of China’s economic expansion has become an expected journalistic subject in Western reports about the country. Such reportage helps provide a salve for the conscience of those enjoying the products of cheap Chinese labour. Judith Doyle and Fei Jun’s GestureCloud, 2010, uses the space of Second Life to rewrite this narrative to great critical effect. In place of the massive lot, but nameless Chinese workers, the artists create a virtual inventory of the gestures factory employees are forced to repeat, ad infinitum, when doing their jobs. Based on video documentation of the duties performed in a printing factory in Beijing, GestureCloud represents these workers in terms of their real-world effects. As with other multi-user online environments, Second Life has a real world economy, money changing hands in the form of Linden Dollars (San Francisco’s Linden Labs is the company behind the site).

One translation of RMB City is Money Town. A mordant commentary on the breakneck pace of economic development in China, Cao Fei’s project also creates a narrative for the transition China is currently undergoing—and the implications it has for the rest of the world. Anyone with a computer and an Internet connection can use Second Life; the language of software is more or less universal. With Princess Iron Fan, 2010, Yam Lau gives expression to the heterogeneity of elements from which this new Global culture is being constructed. Princess Iron Fan is a character from a Chinese folk tale, adapted for a film of the same name that was the first animated feature film made in China in 1941. Lau adopts the figure of Iron Fan as it appeared in the 1941 animation for his Second Life avatar, but with important alterations. Presented in pleasingly anachronistic black and white, the avatar is given certain ghostly characteristics. It is visible from the front but not the sides or back. The artist slyly attributes vaporous qualities to a thing that already has no substance; Princess Iron Fan is perpetually destined to exist on the threshold between the virtual and the actual. In metaphorical terms, the virtual animation of a Chinese folk hero points to the changed cultural landscape that will characterize the 21st century—an expanded world no longer necessarily bound by Western ideas or traditions. ❚

“Residency in RMB City” was exhibited at Gendai Gallery in Toronto from December 4, 2010, to March 5, 2011.

Rosemary Heather is a freelance writer and curator.