René Magritte

It may be impossible to smoke Belgian painter René Magritte’s infamous pipe, but it is easy to inhale the second-hand fumes. Or so it would seem, from the work of 31 artists shown alongside a masterpiece- laden selection of Magritte’s paintings in the entertaining and engaging “Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images.”

The show takes both its title and its intellectual focus from Magritte’s most famous and influential painting (and all its variants), The Treachery of Images (This is not a pipe), 1929, which pairs an image—a larger-than-life cartoon of a European tobacco pipe—with a simple, five-word text: “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” In a gesture that is now utterly digested, thanks in part to a philosophical treatise by Michel Foucault, but was radical for its time, Magritte negated the identity of the painted image with the text, while at the same time stating a simple fact. Of course, this is not a pipe, it is a picture of a pipe, and although it looks like a pipe, it’s not.

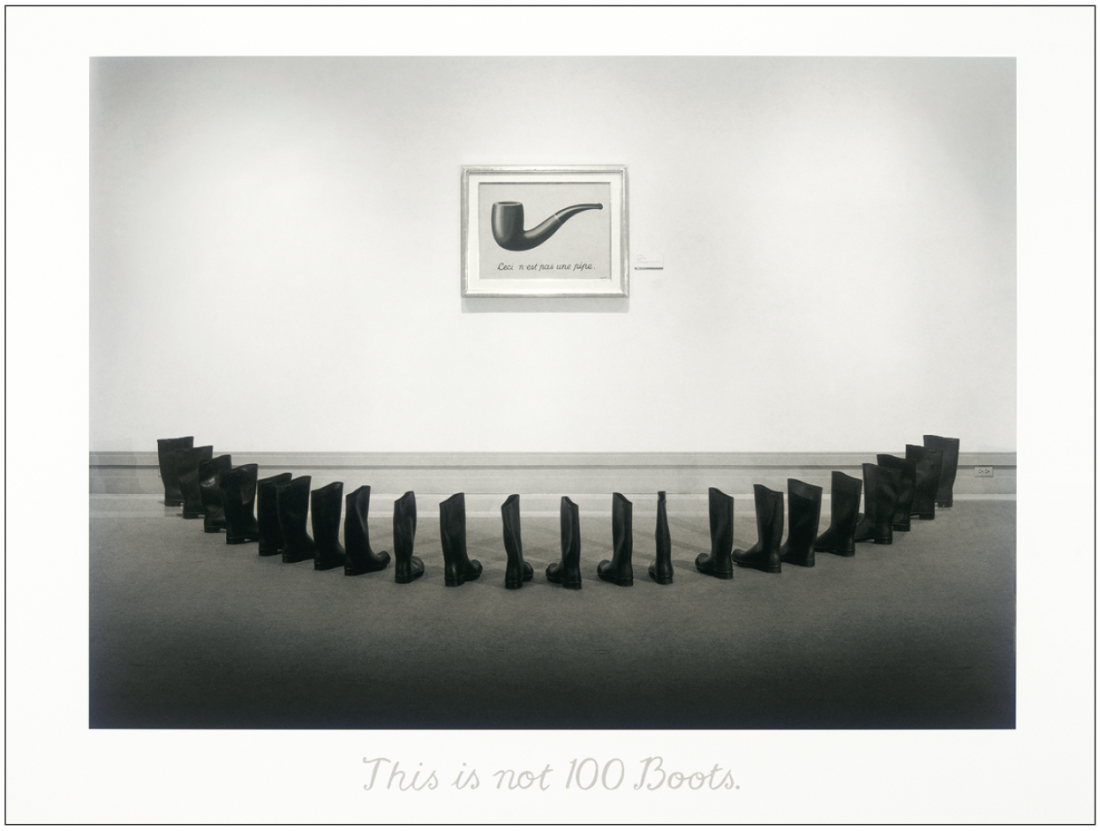

Eleanor Antin, This is not 100 Boots, 2002, Iris inkjet on Somerset satin watercolour paper, ed. 4/10, 88.9 x 120 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo courtesy Lumiere.

Magritte expanded upon this proposition, or “cliché,” as he called it, over the course of his career, and one of the principal pleasures of the exhibition is a series of 18 small drawings from 1928 in which the artist pairs a word and an object— for example, the word “canon” and a drawing of a blob or a rock (a recurring image in later work), and the word “brouillard” (fog) with a drawing of a weight. Beneath the drawing, a caption explains that sometimes words describe something precise, and sometimes they describe something vague, as do images. The rest of the drawings explore other possible pairings— such as what happens when a masonry wall obscures the object depicted—that illustrate the endlessly engaging conundrums that fuelled much of the artist’s work, and what reductively could be called “Magritte’s cleverness,” an ingenuity that has had a marked influence on artists who came in his wake.

Los Angeles-based conceptual artist John Baldessari has repaid his debt to Magritte by designing the exhibition installation in a way that turns the viewer upside-down— papering over the ceiling with a repeated photograph of an iconic Los Angeles freeway cloverleaf, and carpeting the floor with puffy, white cumulous clouds set against a celestial blue sky. The entrance is surrounded by an oversized door frame penetrated by a large amorphous form in imitation of Magritte’s The Unexpected Answer, 1933, allowing the viewer to step into the galleries as if walking into the space of the painting. In a gallery window, Baldessari installs, onto a view of Los Angeles, a decal that overlays the Manhattan skyline, further disjointing the sense of place.

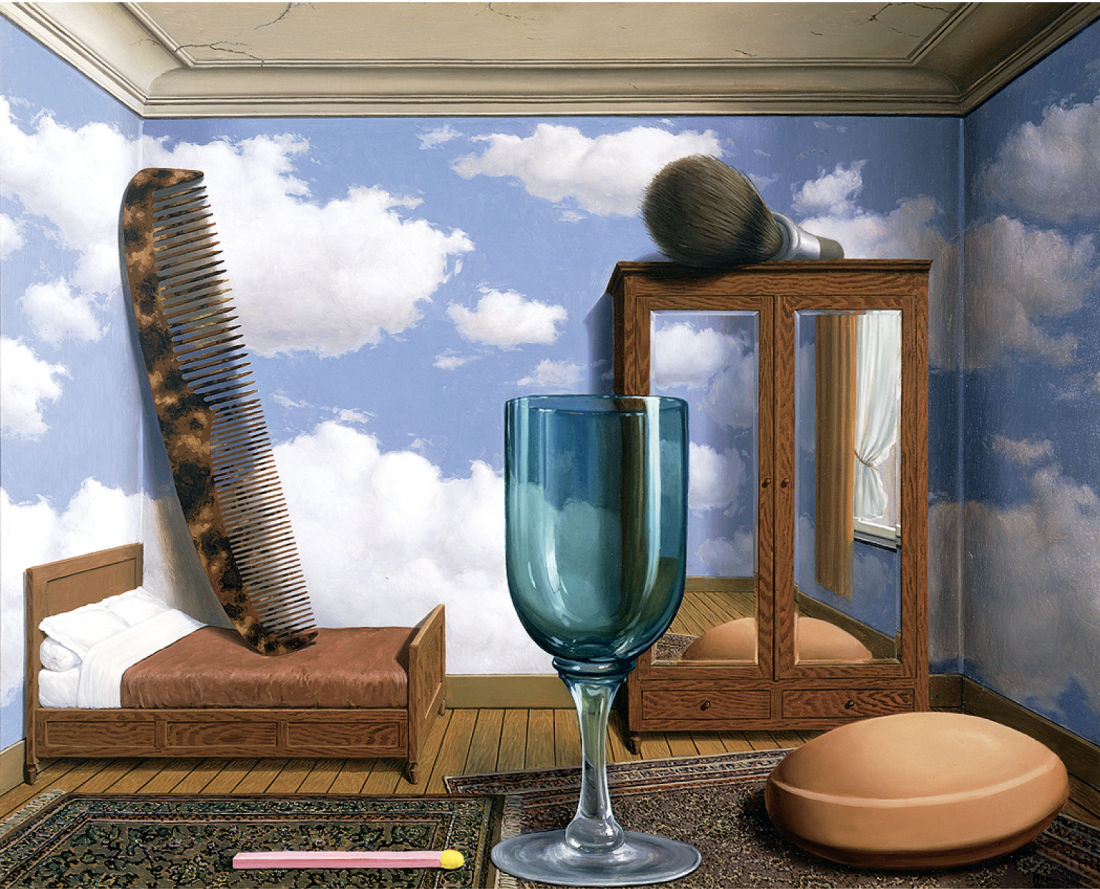

René Magritte, Personal Values, 1952, oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, purchased through a gift of Phyllis Wattis. Photograph: Ben Blackwell.

Some of the contemporary works in the exhibition relate to specific works by Magritte, others to Magritte’s concern in a more general fashion. In a gallery whose intellectual focus is “The Treachery of Images,” Robert Gober is well represented by a 1991 floor sculpture of an enormous cigar. Made from wood, paint, paper and tobacco, this may (or may not) be a cigar, but it is definitely not a pipe. In a room with Magritte’s 1950 painting, The Seducer, a silhouette of a ship painted like the sea upon which it is sailing, and set against a cloud-filled sky, is Jeff Koons’s cast bronze lifeboat. This object, of course, is not a boat, and it definitely is not a life-saving flotation device. Richard Artschwager’s minimalist trompel’oeil formica-on-wood sculpture, Mirror/Mirror—Table/Table, 1964, which also shares space with The Seducer, is an illusion of a mirror and a table, and an obvious joke that remains confounding because of its obtuse accessibility. These sculptural objects are not more or less what they pretend to be than Magritte’s painting of a pipe; and they no longer require the declarative text.

Several works, such as Mel Bochner’s Language Is Not Transparent, 1970—a brief declarative text scribbled over a field of black paint dripping down the gallery wall—and Joseph Kosuth’s Definition (“Thing”), 1968, owe a debt to Magritte’s focus on the ambiguous nature of language. Vija Celmins’s enormous comb, taken straight from Magritte’s painting Personal Values, 1952, and Charles Ray’s gargantuan woman in a red power suit, Fall ’91, owe a debt to Magritte’s incongruity of object and scale. Martin Kippenberger’s The Philosopher’s Egg, 1996, and Philip Guston’s Blackboard, 1969, make Magritte’s reviled art vache paintings of the late 1940s, with their loose brush strokes and garish images, look prescient. Curator Stephanie Barron has even included a brief sampling of work by commercial artists who have appropriated Magritte’s imagery and techniques—in the form of record albums grouped together like a work by Christian Marclay—to present the pervasive influence of Magritte’s iconography.

Robert Gober, Untitled, 1990, beeswax, cotton, wool, human hair, and leather shoe, 27.3 x 52.1 x 14.3 cm. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Ironically, Ed Ruscha, an artist who, in his own right, is a master of pairing image and text, and who has more works in the exhibition than any other of the contemporary artists besides Marcel Broodthaers, who himself had a career obsession with the pipe, rather surprisingly claims, in an interview in the excellent catalogue, not to have been influenced by Magritte’s image-text paintings at all. Instead, he was most interested in the pictorial qualities, such as his repeated use of placing a painting within a painting as in The Human Condition, 1933—a painting of a landscape resting on an easel that obscures the view of the landscape depicted in the painting—and Magritte’s poetic, mysterious titles. Interestingly, one Ruscha painting, Actual Size, of a flying can of Spam has aged into a polyvalency that the artist could not have anticipated when making an icon of the packaged spiced ham in 1962.

The exhibition closes on a wonderful selection of Magritte’s metaphysical everyman paintings from the 1960s, which feature his anonymous bowler-hatted figure. This figure has often been interpreted as a stand-in for the artist who chose this bourgeois attire and an easel in the living room over the antics of his surrealist cohorts. But in the one miscue of the installation, Baldessari has brought this figure to life by dressing the museum guards in a similar fashion. However, the cheap hats and badly fitting uniforms look nothing like what might be worn by a smartly dressed man in a magical universe. The guards stand out, awkward and embarrassed, as if the joke were on them, when, in fact, despite the charm of Magritte, he was dead serious about what he was proposing. ■

“Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images” was exhibited at Los Angeles County Museum of Art from November 19, 2006, to March 4, 2007.

Susan Emerling is a writer living in Los Angeles.