“Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet”

The exhibition’s title suggests comprehension: 23 contemporary Iranian artists living in and outside of Iran, addressing specific conditions under the guise of seductive characters. This is a socio-political history too complex to unpack in such a large group show, and in the era of Donald Trump it is a challenge to experience the work with his cantankerous influence creating such a shadow. Nevertheless, the exhibition at Aga Khan Museum conveys a contemporary Iran, clearly depicting women’s continued struggle for freedom (note: over half of the artists in the show are female) and illustrating the agonizing consequences of war. It also meanders and fragments, failing to achieve a coherent theme or conversation. Of the 27 works gathered from the collection of Mohammed Afkhami and the Afkhami Foundation, the most compelling succeed via tacit gestures.

The two introductory sculptures arrive with audacity: an industrial oil drum painted red, emblazoned with decorative flora, bleeding bullet holes and stags that butt heads. Oil Barrel #13 by Shiva Ahmadi sits adjacent to three metal cylinders topped with scarlet neon lights. Tulips Rise From the Blood of the Nation’s Youth, by Mahmoud Bakhshi, presents one neon flower atop each of the steel cylinders symbolizing Allah and the martyrs of the Islamic Revolution of 1979. In conjunction with their stark glow, the drone of the lights is a deathly dirge. In a symposium associated with the exhibition, Anishinaabekwe curator and self-proclaimed “word warrior” Wanda Nanibush astutely stated, “Sometimes being a rebel means going against your own,” in this instance even against your own breathing body.

Khosrow Hassanzadeh, Terrorist: Khosrow, 2004, acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas. © Khosrow Hassanzadeh. Courtesy of the Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

The continued psycho-socioemotional conflict between Iranian men and women is established through the ostensibly masculine introduction to the show (erect metal canisters, oil, money and martyrs) with its female-made counterparts nearby—work made by women about women that clearly declares that rebels are also female. In Shirin Neshat’s black and white photograph Untitled, 40 women dressed in burqas walk toward the sea. In the middle right, two burqas float on the surface of the water near the shore, drawing attention to their bodies’ absence. The women’s imminent submersion in the sea creates a tense but lyrical relationship between freedom and imprisonment, between the surface of a fabric that restrains and the surface of the water that frees. Escaping land and burqa, they break boundaries, an action tripled in tension since the recent “build a wall”/ travel ban president took office. Nearby, Parastou Forouhar’s piece titled Friday makes sly language of a chador. Four large colour photographs printed on aluminum panels depict a larger expanse of the black cloth. On the third panel from the left, a hand dares to emerge, its folds pulling the viewer’s eyes upward to where the head should be. Fragmented and sly, concealed or in fantasy, a woman’s body provokes, and imagination is still free.

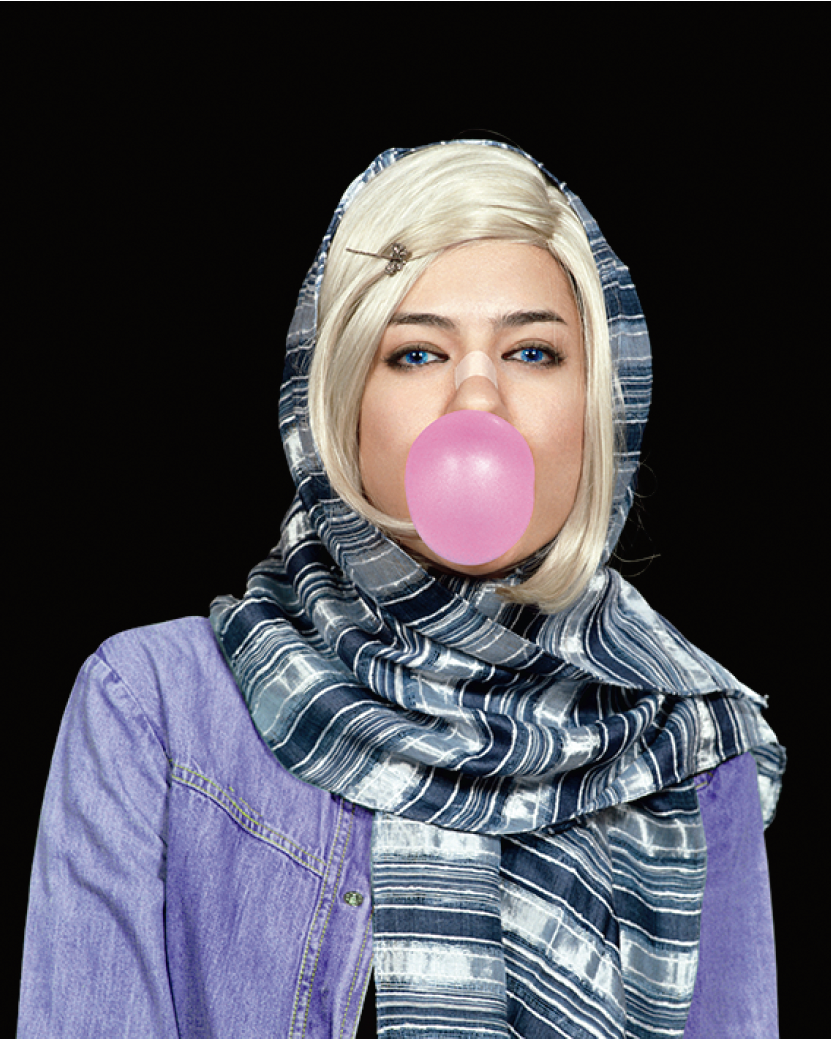

I am struck by the power of women’s enterprises against tradition, even if with Shirin Aliabadi it means succumbing to the toxic trivialities of Westernized beauty. In a C-print titled Miss Hybrid 3, pop culture is literally and figuratively explored via an image of a woman blowing a huge bubble-gum bubble, a bandage on her nose indicating cosmetic surgery. The attraction and simultaneous repulsion of the West are productive in this work, the didactic panel accurately pronouncing “cultural rebellion meets Christina Aguilera.” Poking fun at themselves for our entertainment while coyly mocking those around them, Khosrow Hassanzadeh and Aliabadi make ironic pinky-purple, dreamy portraits that address very real concerns.

Hassanzadeh confronts the viewer with an impossible answer to an insidious question, what does a terrorist look like? Using the West’s delusional and yet sanctioned codes of fear, paranoia and discrimination to question the prevailing stereotypes associated with Iranian men, he literally tagged the piece with a paper certifying his identity: “Terrorist.” (I’m sure some people will appreciate the clarification.)

Shirin Aliabadi, Miss Hybrid 3, C-print. © Shirin Aliabadi. Courtesy of the Mohammed Afkhami Foundation.

Out of the confines of the partitioned galleries and into the grand balcony overlooking the main floor’s ancient exhibits, the sensibility of the exhibition shifts from the personal and secular to public, spiritual and abstract. A large work by Alireza Dayani titled Untitled (from the “Metamorphosis Series”), which was drawn using ink on cotton rag, Rokni Haerizadeh’s oil painting titled We Will Join Hands in Love and Rebuild Our Country and Ali Banisadr’s We Haven’t Landed On Earth Yet render an otherworldliness not evident in the rest of the exhibition. They help to unite in the expansive U-shaped corridor the other 11 works that are otherwise disjointed and randomly configured.

Alireza Dayani’s subterranean black ink drawing depicts fish-eating fish, toothed anemones and squid whose tendrils reach outside the picture plane. I get the sense that delusion is becoming illusion, is becoming metaphor. Feeling slightly hallucinogenic, I am led deeper into a haze created by Ali Banisadr’s indistinguishable forms and psychotropic colours, which prophesize a shared plight. In his painting chaos reigns supreme in aquamarine, spiral yellow coils and violet mushroom-shaped huts. The shapes, however, seem irrelevant as the artist draws us closer to sensation than meaning, and as a result, I become future oriented. The question becomes not what is the relationship between these Iranian artists or between Iranian and Western culture, but what will be? If, according to Banisadr, bodies / forms are obsolete, we must depend on the sensual intuition to navigate experience. Rokni Haerizadeh’s nearby oil painting suggests that spiritual help has arrived: a mystic approaches, riding backward on a donkey stuffed with people.

I realize it is people rather than conflict that the show addresses. Part of the Aga Khan’s mandate is to facilitate individual expression amidst the oppression of a monolithic regime. In this exhibition obscurity and abstraction produce a much-needed “gap” in role playing, a place where artists can stick their head out and say this is the real me. Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet are interesting but perhaps limiting categories and I see that, because of bombastic Western influences, and cultural, psychological and political unrest, “real” contemporary Iranian artists are yet to be revealed, at least according to their own distinct parameters. However unknown, that is an exciting place to be. ❚

“Rebel, Jester, Mystic, Poet” was exhibited at Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, from February 4 to June 4, 2017.

Jasmine Reimer studied visual art at Emily Carr University and the University of Guelph. Upcoming projects include residencies at the CAMAC Art Centre in France and the Institute fur Alles Mogliche in Berlin. Her most recent body of work is on view at Projet Pangee in Montreal in a two-person exhibition with Andre Ethier.