Rebecca Belmore

Rebecca Belmore’s midcareer survey at the Vancouver Art Gallery highlighted the connection between her performance practice and her work across other disciplines, including sculpture, installation, video and photography. Although this was hardly a new way of viewing Belmore’s art, it still proved useful in identifying her overarching themes, creative strategies and evolving use of media and materials. Arguably, all her work is grounded in performance, her first discipline; sometimes it involves herself as subject, as seen in her astounding video installation Fountain, which debuted at the 2005 Venice Biennale, and sometimes it involves a model, a kind of surrogate performer, as seen in a number of her still photographs. A sleekly edited program of five of Belmore’s dedicated performance works, dating from 1991 to 2008 and recorded on video, was on view in a corner of the gallery. The sounds, gestures and fierce imagery of that program reverberated throughout the show.

Common to all Belmore’s work is seeing the body as means and metaphor, as claimant to the natural world, testament to history and stage of ongoing struggle. Recurring references to the body were part of the VAG’s reading of Belmore’s work, along with what the curators described in the catalogue as “the specificity of place and nature, and the determined response to the socio-political conditions of the moment.”

The performance connection was eloquent in the two most recent works on view, Storm and Making Always War. The former, a floor-mounted sculpture fashioned from a split cedar log, desert camouflage fabric and flat-headed brass nails, was created for the exhibition, which opened this past June. It evolved directly from the latter, a performance Belmore had delivered outdoors on the campus of the University of British Columbia a few months earlier, and on view here as a video document.

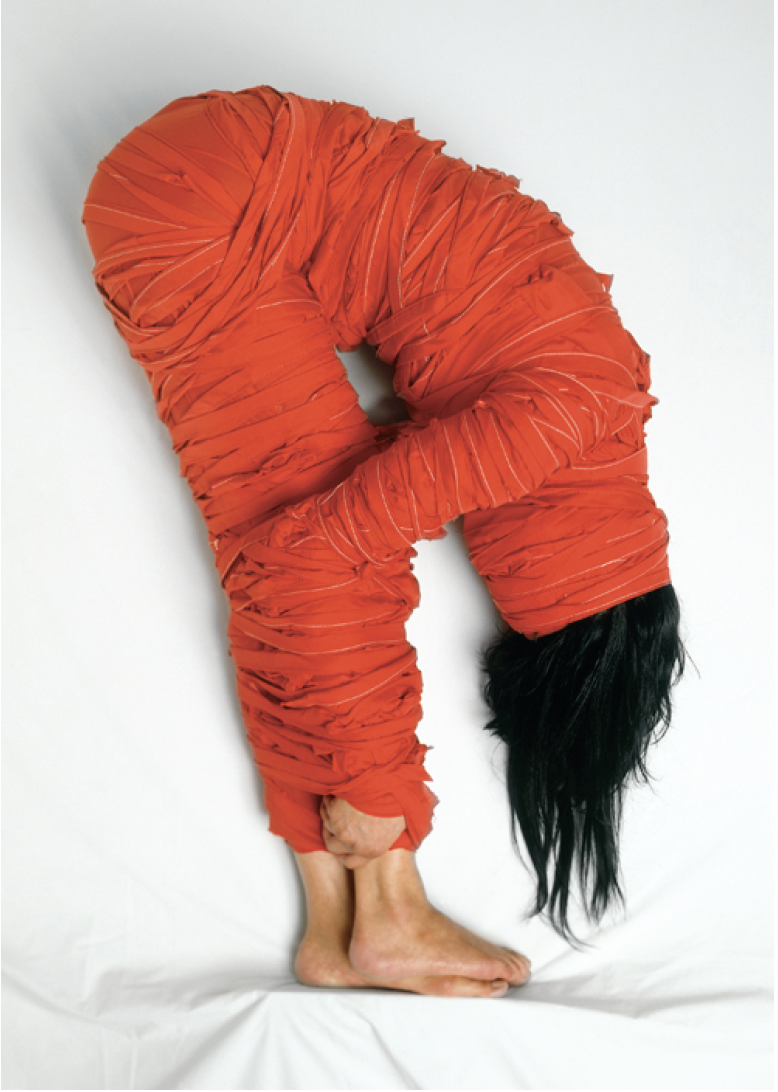

Rebecca Belmore, Untitled 2, 2004, three inkjet prints on watercolour paper. Collection of Donald Ellis and Mary Ann Bastein. Photo courtesy the artist.

Both works saw the nailing of camouflage fabric, which had been manufactured in the United States for military use in Iraq, to large, log-like pieces of wood. And both speak to a multitude of dire interrelationships: nature and culture, creation and destruction, potentiality and realization. The links between environmental exploitation, corporate hegemony, globalization, warfare and the military-industrial complex are all alluded to in Belmore’s simple acts and modest materials. The denatured wood— stripped of bark and subtly polished, or shaped into a rough beam salvaged from a demolition site— ably symbolizes the human body. Its wrapping or draping in camouflage fabric articulates the violent irony of human beings disguising themselves as their natural surroundings while engaging in acts antithetical to nature: mass murder and wide destruction.

In the performance, Making Always War, Belmore’s own body was present and active as she furiously tore open camouflage-pattern shirts, wrapped them around the beam and hammered them in place so the wood was entirely upholstered in the fabric. Sunset slid into dusk and dusk into darkness. Pow-wow music played on the tinny sound system of a little pickup truck, whose headlights illuminated the action. Eventually, Belmore and colleague Daina Warren erected the beam vertically, like an obelisk, a war monument, a dismembered cross. Then they drove away.

In Storm, Belmore’s physical presence is subsumed within the sculpture’s making. Other bodies— the political body, the soldier’s body, the shrouded corpse of a tree—remain to bear witness. The title of the sculpture calls up the falsely elemental battle name “Desert Storm” and also the actual hurricane-strength winds that felled so many thousands of trees on the West Coast two winters ago. But of course, destructive acts of nature can be cycled back to destructive human acts. War over control of the world’s oil reserves is played out against the obvious results of hydrocarbon exploitation: global climate change and violent extremes of weather.

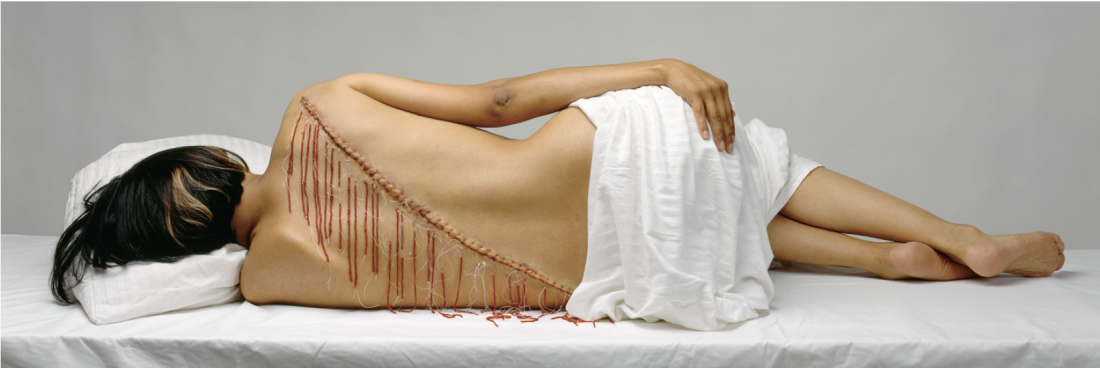

Rebecca Belmore, White Thread, 2003, inkjet on watercolour paper. Collection of Kamloops Art Gallery. Photo courtesy the artist.

The earliest work in the show was Rising to the Occasion, a 1991 version of a performance costume Belmore produced and wore in 1987. It is a dramatic prop that is also a freestanding sculpture, a dress that is also a habitation, a record of an ephemeral act that has contrarily sustained a physical presence. The work melds elements of a Victorian ball gown with “Native” stitchery, buckskin fringe, porcelain saucers, royal kitsch and memorabilia, and a beaver-den bustle of rough sticks and twigs. Originally created for a performance to protest a royal visit to Thunder Bay, it is a condemnation of the marketing of the vestiges of colonialism in the form of royaltouristic- Native events and souvenirs. It is humorous and angry in equal measure, using the conflation of stereotypes to defy, well, the conflation of stereotypes.

Belmore’s later work is more mysterious and, at the same time, more elemental. Complication is replaced with complexity, immediacy of access with a compelling depth. Wild, for instance, consists of a grand, four-poster bed adorned with rich fabric, hair and fur. Beaver pelts have been incorporated into the canopy and masses of long black hair have been sewn onto the bedspread. Belmore originally produced this work in 2001 for an intervention/exhibition at The Grange, the 19th-century mansion that was the original site of what is now the Art Gallery of Ontario. Throughout that exhibition, Belmore created unscheduled performances in the bed she had dressed with hair and fur, slipping into it in its master-bedroom setting and lying, sleeping and lounging there naked. It was a subversive form of reclamation, the reinsertion of her presence, her identity into a history from which Aboriginal people have been erased. The work also took on issues of gender, sexuality and class, again speaking to the construction of privilege and the exclusion of certain peoples from the realms of power.

At the VAG, the bed covering was visually compelling, with its multiple thick fringes of straight black hair. The hair is both alive and dead, creating a forceful presence and, at the same time, evoking genocide, ethnic cleansing, erasure. Still, the work’s full dramatic power was muted by its removal from its original, site-specific context of historical house and animating performance.

Rebecca Belmore, The Great Water, 2002, canoe, fabric, metal grommets, powdered carbarundum. Collection of Thunder Bay Art Gallery. Photo: Howard Ursuliak, courtesy of the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery.

One of the most extraordinary of the nine colour photographs on view is Fringe. Originally mounted as a conspicuous billboard in Montreal in 2007, it was staged at the VAG as a slightly larger than life-size, backlit transparency. The image has remained the same: a black-haired, olive-skinned woman lies on her left side, facing away from us. She reclines naked on a white sheet against a pale grey ground with a white cloth draped over her hips and her buttocks. The smooth expanse of her skin, however, is dramatically disrupted: a long diagonal scar runs from her right shoulder to her left hip. This lengthy wound is crudely sutured with dangling white threads, on which are strung small red beads. Hanging vertically, the beaded threads look like streams of blood.

Belmore’s work knowingly deploys the slick, sexist conventions of both advertising and art to speak to the violence of history, especially violence borne by Aboriginal women. It is in many ways significant that the ghastly wound of the reclining figure has been dressed with beads, a medium of understated cultural and historical complexity. Here, the bead work calls up indigenous traditions, handed down from mother to daughter; Native adaptation of materials introduced by colonialism; the absorption of a socially integrated art form into an alien medium of exchange; and the creation of an uncertain commercial bridge to the future. Although grievously wounded and undoubtedly traumatized, the unnamed woman depicted here also manifests the ability to heal. She has been slashed, scarred, irrevocably altered—but she is still alive, resting, recovering, regaining strength and purpose.

Belmore’s Fountain was beautifully restaged for her Vancouver retrospective. In the Canadian Pavilion in Venice, the video had been rear-projected onto a screen of running water. In a purposebuilt gallery at the VAG, it was front-projected onto a Plexiglas screen, over which water comprehensively flowed. The water amplifies the entire work, almost carrying it into another dimension.

Rebecca Belmore, Fringe, 2008, transparency in lightbox. Photo courtesy the artist.

The video opens with a downward panning shot, from a wintry, West Coast sky to a beach strewn with driftwood, then along the beach to a pile of logs that suddenly explodes into flames. On the soundtrack, the roar of the fire merges with the scream of jet engines—an unseen passenger jet descending through the clouds. (The rumbling and vibrating of the gallery’s false floor, beneath which the sound equipment for the piece was located, created a thrilling kind of sense-surround effect.) The camera then cuts to an expanse of cold, grey ocean. In shallow water, near the shore, a wet and distressed woman struggles with something, gasps, shakes her head, falls, flails around, struggles and gasps some more. Eventually she sits calmly, almost meditatively, holding the object—an old red bucket—in front of her like an offering. The camera pulls back, she stands, carrying the full bucket, and walks toward us, across the beach, over the stranded logs and the sandy clumps of seaweed. With an immense groan—of effort, of rage, of suffering—she throws the contents of the bucket at the camera. Blood covers the lens, and through its viscous red veil, she stares at us. And stares.

At the VAG, the gasps and groans in Fountain reiterated the enraged and effortful sounds emanating from the video of Belmore’s Creation or Death, We Will Win, playing in another part of the gallery. A 1991 performance she gave at the Havana Biennale, Creation or Death shows Belmore frantically labouring up a long flight of stairs on her hands and knees, shoving an ever-diminishing pile of sand in front of her. Her feet and hands are bound, a rope is pulled tight across her mouth, and her sounds and actions are increasingly agitated. What both works indicate is that across a wide expanse of time and circumstance, Belmore engages her body in the action and metaphor of struggle.

Fountain is so rich with meaning, metaphor and evocation that it’s hard to know where to begin analyzing it. Shot in midwinter on an island at the mouth of the Fraser River, it alludes through place to the present and the past, to the Musqueam First Nations reserve, the Vancouver International Airport, lumber mills and a sewage treatment plant, all located nearby. It also plays with the elements, with cosmologies, prophecies and creation myths, with the violence of history, fear for the environment and the need to acknowledge our shared humanity. The agitation, the struggle, the blood suggest violence and suffering, but they also evoke offering, expiation, atonement—within not one culture but many. ■

“Rebecca Belmore: Rising to the Occasion” was exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery from June 7 to October 5, 2008.

Robin Laurence is a writer, curator and a Contributing Editor to Border Crossings from Vancouver.