“Rearview Mirror: New Art from Central and Eastern Europe”

A couple of years ago, I spent a strange night in Belgrade, Serbia, with a talented young sculptor just out of the Belgrade Academy of Fine Art. At one point she lead me through a network of dark alleys and courtyards and up the back stairwell of a dilapidated building to a spacious rooftop dance club. There were red lamps and fake palm trees; electronic music pounded. “This is where we came to party during the American bombing,” she told me. “You could see it from here!” And then a little later she added, darkly, “don’t believe everything people tell you about Serbia.”

I was reminded of that night as I watched Serbian artist Dušica Dražić’s Young Serbians, 2006, which is included as part of “Rearview Mirror: New Art from Central and Eastern Europe,” curated by Christopher Eamon for the Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto. The exhibit will travel to the Art Gallery of Alberta in January 2012. In Young Serbians, a young woman stands in tall grass along a highway in the flat prairies that sweep across Serbia, dancing as a man sings in English an off-key send-up of David Bowie’s “Young Americans.” “All night,” he bellows without accompaniment, “we were the young Serbians, the young Serbians, we were the young Serbians.” The cars rushing past behind her, she dances with a torpid, flailing lack of enthusiasm. Serbia had an unusually bitter 20th and early 21st century: the First World War, the Second World War, which doubled as a civil war within what became Yugoslavia, then a half century of socialist dictatorship, then another civil war, then another more malignant dictator. Young Serbians are weary of history and just want to dance, but aren’t quite up to it.

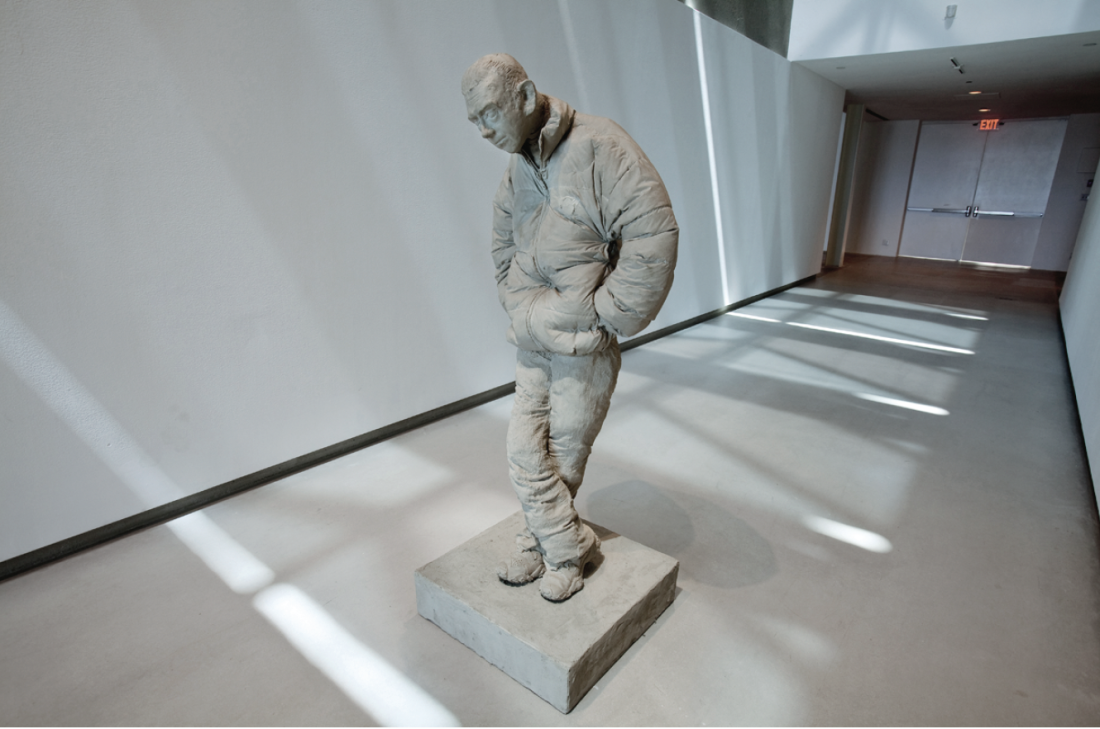

Paweł Althamer, Guma, 2008. Installation view at The Power Plant, 2011. Photo by Steve Payne. Courtesy the artist.

The woman in Young Serbians isn’t the only figure in “Rearview Mirror” who is a little lost and at loose ends. In Slovakian artist Roman Ondák’s The Stray Man, 2006, a man is wandering about the streets of what looks like the downtown tourist district of a German city. It is early morning, the shadows sharp and long; streetcars pass, people on bicycles glide by on their way to work. He loiters at a bus stop, pacing back and forth, occasionally peering through the tinted window of a closed bank, or perhaps an art gallery. For Guma, 2008, well-known Polish artist Paweł Althamer made a life-sized polyurethane sculpture of a drunk in a neighborhood in Warsaw where he has his studio. A uniform grey, he is slightly hunched over, wears an old parka and has his hands stuffed in his pockets. Guma is a monument to the lost.

Although many artists in “Rearview Mirror” would scarcely remember communism, some of the most compelling work in the exhibit glances back toward that era. In Romanian artist Annetta Mona Chis¸a and Slovakian Lucia Tráčová’s collaboration, Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (Let’s Conclude), 2008, young women in snappy red uniforms, hats and white boots wield batons as they march in formation along the bleak underpass of a bridge, cars screaming past overhead. These majorettes are, it turns out, broadcasting the heroic revolutionary tract of 1912, Manifesto of the Futurist Woman (Let’s Conclude), using a secret, semaphore code. For his stunning two-channel video installation Out of Projection, 2009, Croatian artist David Maljković brought together retired Peugeot designers from a plant in Zagreb. Seen on a smaller screen, they sit in front of the wall of a high modernist building talking. On another, they assemble in pairs, frozen along a road in a forest with space-age cars, and then on a test track in a clearing, as though the Futurist vision of design and technology had become, literally, an uncanny dream. The darker side of the communist and Cold War era is explored by Lithuanian artist Deimantas Narkevičius. The Dud Effect, 2008, begins with a camera tracking through the twisted ruins of a Soviet-era military installation. The remainder of the film consists of a detailed re-enactment by a former Russian officer of the final procedures in the launch of a nuclear warhead. He barks out codes, answers phones; he presses buttons. Armageddon would have been started by a bureaucrat mechanically doing his job.

Anna Ostoya, Work by an Artist Inspired by a Theory About Modernity, 2007. Installation view at The Power Plant, 2011. Photo by Steve Payne. Courtesy the artist.

Contemporary artists are preoccupied with the history of art and the heritage of Modernism, and that is as true of Eastern and Central European artists as of anywhere else. Twenty-eight-year-old Polish artist Anna Molska’s video Peers, 2010, opens with a male voice denouncing harp music, canaries, the tendency of students to undress in the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts studio of legendary teacher and sculptor Grzegorz Kowalski, and the poetry of Nobel Prize winner Wisława Szymborska. Inevitably, Molska ends up topless swinging on a hammock in a room with orange canaries and a woman playing harp; an early Szymborska poem is recited backwards. The prodigiously talented young Polish multi-media artist Anna Ostoya is more directly engaged in ironizing Modernism. In Work by an Artist Inspired by a Theory About Modernity, 2007, for instance, she constructed a white pedestal with a plastic bag on top, a fan blowing underneath it, and for From A to Infinity, 2007, she collected newspaper clippings and cut them up to form a pyramid in a glassed-in box.

Twenty years ago, I found myself in the East Berlin train station waiting for a train to Vilnius shortly after the Soviet military’s tumultuous final withdrawal from Lithuania; a month later, on Christmas day, 1991, the Soviet Union officially dissolved. Signs in the grim, poured concrete station announced destinations that were once part of the communist world: Riga, Minsk, Warsaw, Kiev, Budapest and Bucharest. That world has become an historical relic, replaced by varying modes of capitalism and varying degrees of democracy or authoritarianism. In the meantime, the rest of the world has changed as well: more global, less rooted in nation or region, more abstracted, probably less meaningfully democratic. “Rearview Mirror” arrives at a moment when the fact of artists being from Eastern or Central Europe or anywhere in particular means less than it ever did, and for that reason the exhibit feels disconnected and haphazard. Christopher Eamon’s poorly written essay for the exhibition’s catalogue does not make the project any more coherent. Nonetheless, there are, as always, excellent artists out there, wherever “there” happens to be, and some of them are in “Rearview Mirror.” ❚

“Rearview Mirror: New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” was exhibited at the Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto, from July 1 to September 5, 2011.

Daniel Baird is a Toronto-based writer on art, culture and ideas.