Rajni Perera and Marigold Santos: Efflorescence/The Way We Wake

The first time that I encountered the work of Marigold Santos and Rajni Perera was at a 2020 group show called “RELATIONS: Diaspora and Painting” hosted by the PHI Foundation, curated by Cheryl Sim. I was asked to contribute essays to the book accompanying the exhibition and although Santos and Perera were not my assignments, I distinctly remember their paintings. Both Santos’s shroud (in threadbare light) 1 and 2, 2020, and Perera’s Ancestor 1 and 2, 2019, exuded a profound stillness that registered as a sense of calm, rather than imposed stasis. Each painting featured a single not-quite-human subject—Santos’s female figures were woven in shades of black, with a pastel desert-like landscape appearing between the spaces of the weaves, while Perera’s figures were like aliens and adorned in colourful, opulently patterned garments; their gazes were fixed somewhere beyond the confines of the canvas.

“RELATIONS” is also where Perera first encountered the work of Santos, and where the early seeds of “Efflorescence/The Way We Wake” were sown. Referencing the birth of their relationship as a process of germination seems apt for two artists who demonstrate devout reverence for the botanical world and whose processes seem communally generative and intertwined. Perera’s feeling of a deep sense of personal identification with Santos’s paintings would eventually result in her inviting Santos to collaborate with her to create a duo presentation at the 2023 Armory Show in New York, where the conception for the present exhibition featuring new and recent works by both artists coalesced.

In tracing back both artists’ work, it is not hard to see Santos reflected in Perera and vice versa. The similarities are impressive. Both immigrated to Canada as children with their families—Perera (b. 1985) from Sri Lanka, and Santos (b. 1988) from the Philippines. Both are storytellers using speculative and folkloric frameworks to address such themes as identity, migration, gender, colonialism, environment and shifting conceptions of home. They are both spectacularly interdisciplinary, unafraid to explore new media and techniques, a range of which is featured in “Efflorescence/The Way We Wake.”

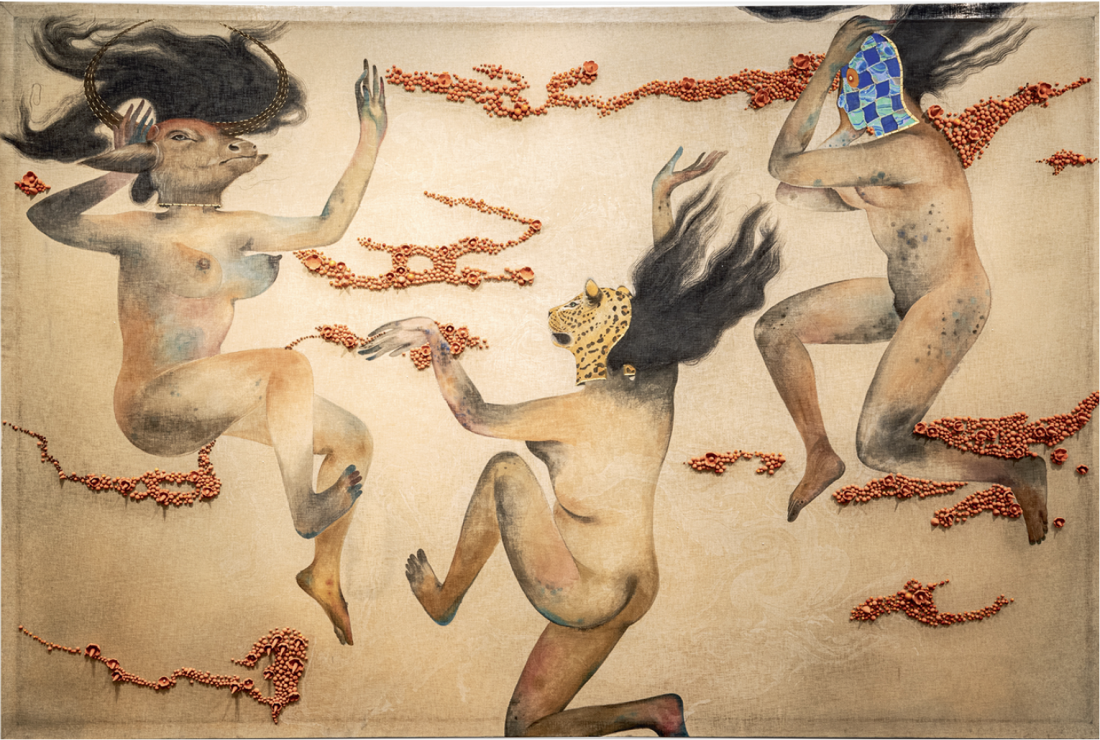

Rajni Perera, I Couldn’t Wait Longer, 2023, polyester, acryl-gouache, chalk, charcoal, gel pen, gold metallic thread, polymer clay beads, glass beads, wooden beads, aluminum and wood frame, 243.8 × 365.8 centimetres. Photo: Mikhail Mishin. Courtesy the artist, Patel Brown Gallery, Montreal, and PHI Foundation, Montreal.

Entering the space, you are confronted by Efflorescence/The Way We Wake, 2023, after which the exhibition is named. This large clay and mixed-media sculpture, which is both a body and a biome, is positioned in a way that suggests this femalepresenting creature was anticipating your arrival (you certainly could not say the same). She is poised on her belly, and her torso is held upward by her arms, anchored by hands pressed into the ground, outstretched fingers decorated with tattoos that resemble the contour lines of topographic maps; at her fingertips are sharpened claws. Her eyes peer through an elongated mask whose surface is ornately finished. Long black hair cascades down her nape onto her back like a river following gravity’s pull, reminding you that this is also a landscape. Between the arms, elongated breasts with ornamented tips touch the floor and are surrounded by stones fashioned out of clay—some remain an ochre colour and others are painted black. Tufts of moss cling to their surfaces and brambly stems extend upward to display wispy black blooms and ochre bulbs.

Walking around the sculpture, you discover that the legs are detached and rest at unnatural angles a slight distance from the torso. Here, I refrain from using the adjective “broken” to describe this body— partly in resistance to the ableism that has been replete in art history, where, across centuries, symmetry (and Whiteness) has provided the limited structural definition of beauty, particularly in terms of the female body. Furthermore, the scene does not suggest violence but rather seems generative, as depressions in the unattached limbs host tiny ecosystems that echo the geological and botanical features that surround the breasts—the legs, it seems, have lives of their own. It is a testament to the artists’ magical dynamism that a sculpture, which science would deem an “inanimate object,” could be activated to so fulsomely tell a story, which I read as referential to aswang, mythological figures in Filipino folklore—an enduring central figure in the work of Santos. Prior to colonization by the Spanish, aswang were considered priestesses and shamans; post-colonization, the Spanish conceived them as self-segmenting, viscera-sucking, vampire-like monsters. I could spend the entirety of my word count on this piece alone. However, far from being a solo mainstage, the sculpture established the tenor of magical hybridity that would be maintained throughout the exhibition.

Perera’s large painting I Couldn’t Wait Longer, 2023, occupies the entire wall behind the sculpture, seemingly mirroring the afterlife or otherworld inhabited by the heavy body on the floor before it; in this ethereal world she is whole and multiple. In the painting three nude female figures wearing masks hover, suspended in playful animation, their long black hair floating upward in defiance of the laws of gravity, their body gestures holding no right angles. The colour palette echoes the ochres, blacks and greys of the sculpture, save for a blue checkered mask worn by one figure. The surface of the canvas is detailed with agglomerations of polymer clay beads forming atmospheric wisps, which in the natural world would be gaseous but in this one are solid. Most wonderful, though, are the occasional tiny glass beads handsewn onto the canvas as a gift for the attentive observer. This beadwork and many delicate signatures of the hand reappear throughout Perera’s oeuvre.

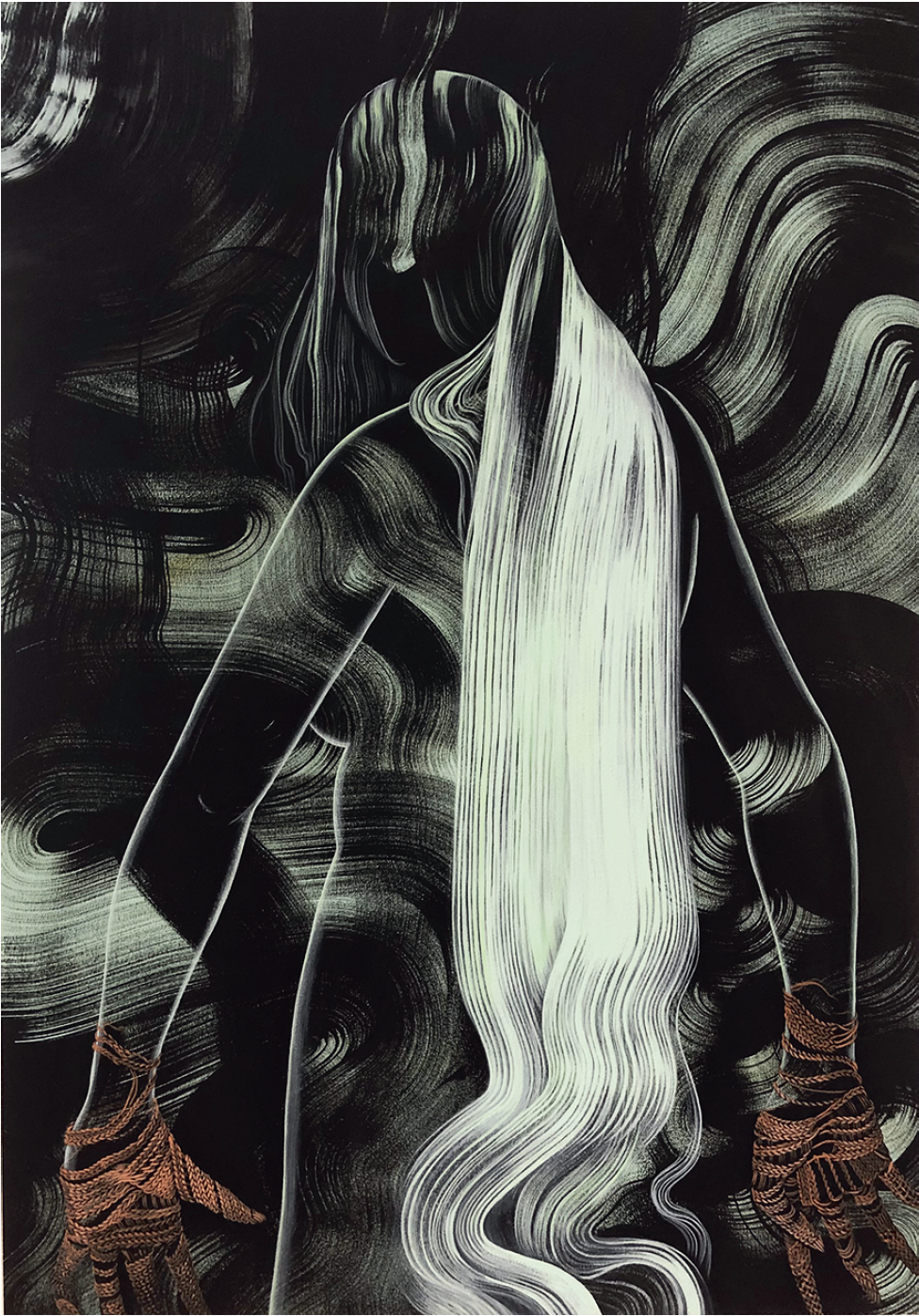

Marigold Santos, shroud envisioning (glance in green), 2022, acrylic, pigment, gesso on canvas, 101.6 × 71.1 centimetres. Courtesy of Brendan and Jacob MacArthur-Stevens. Image courtesy PHI Foundation, Montreal.

The work of Santos continues the theme of suspension and movement in an installation of four large paintings titled shroud tinikling, 2022. Housed on the fourth floor of the gallery, this work is accompanied by an audio and sculptural component. Each canvas is occupied by a singular female figure whose legs are woven in black and grey strands. The torsos of two of them are solid and are detailed with undulating lines that resemble wood grain or cartographic contours. The figures in the two central panels dance over two thin poles that run horizontal to the lower quadrant and continue onto the adjacent canvas, and the figures at the ends hold the poles essential to the tinikling, a Philippine folkloric dance. The dancers merge into moody pastel or faded landscapes whose tenor changes through the chosen colour, while figure and ground do this marvellous exchange of foreground and background. An exceptionally low horizon line runs throughout the panels so that atmospherically rendered sky dominates each canvas. The discreet power in these pieces is activated by Santos’s audacity to reject the traditional horizontal “landscape” orientation, instead turning the length of the panel upward to create vertical landscapes. I am a scholar of landscape and perspective, a lover of stories and someone with a penchant for the concept and aesthetic of suspension, and these paintings made me sigh.

A quiet marker of the collaborative success of “Efflorescence/The Way We Wake” is the harmony conjured by Perera, Santos and curator Cheryl Sim—there is no sign of competition or conflict, and in a world seething with these qualities, visitors will be grateful for this built environment that is antithetical to aggression. Both artists conceptualize shrouds or garments as holding protective power, and I think how the architecture of this exhibition space provides a momentary armour of refuge honouring egality, compassion and altruism; outside is elsewise. ❚

“Rajni Perera and Marigold Santos: Efflorescence/The Way We Wake” was exhibited at the PHI Foundation, Montreal, from May 3, 2024, to September 8, 2024.

Tracy Valcourt is a writer who lives in Montreal, where she has been a part-time professor in the Department of Art History at Concordia University. She currently holds the position of assistant professor of Interdisciplinary Arts in the School of Social Sciences, Arts, and Humanities at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco.