Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread mines a narrow vein of materials—plaster, rubber, resin, aluminum—and preoccupations—the voids surrounding or contained by buildings, furnishings and quotidian objects. Known primarily as a sculptor, she employs the built environment as a mould for the non-material world, making her work less about architecture than about the souls that inhabit the space the architecture models.

As a draughtswoman—as is amply evidenced in a voluminous selection of spare and largely monochromatic drawings that are on display at The Hammer Museum in the artist’s first retrospective of works on paper—she frets over the same terrain, exercising a deliberate mise en page and lack of notation that makes it clear that her drawings are discrete works of art. They amplify but are not necessarily preparatory to her sculptural work. Reluctant to have them misunderstood, she has largely kept them as a private record for her personal reference.

Through careful thematic groupings—rooms focusing on chairs, floors, beds and bathtubs—curator Allegra Pesenti elaborates on the singular nature of Whiteread’s pursuit while illuminating the unexpected variety of techniques and styles, as well as the mystery and feeling that pervades this surprisingly emotive body of work. Whiteread’s unorthodox materials—correction fluid, resin and varnish—mimic those she favours in sculpture, with careful drips weeping down the page and underlayers of colour seeping through to the surface, producing a profoundly humanizing effect from these inanimate objects.

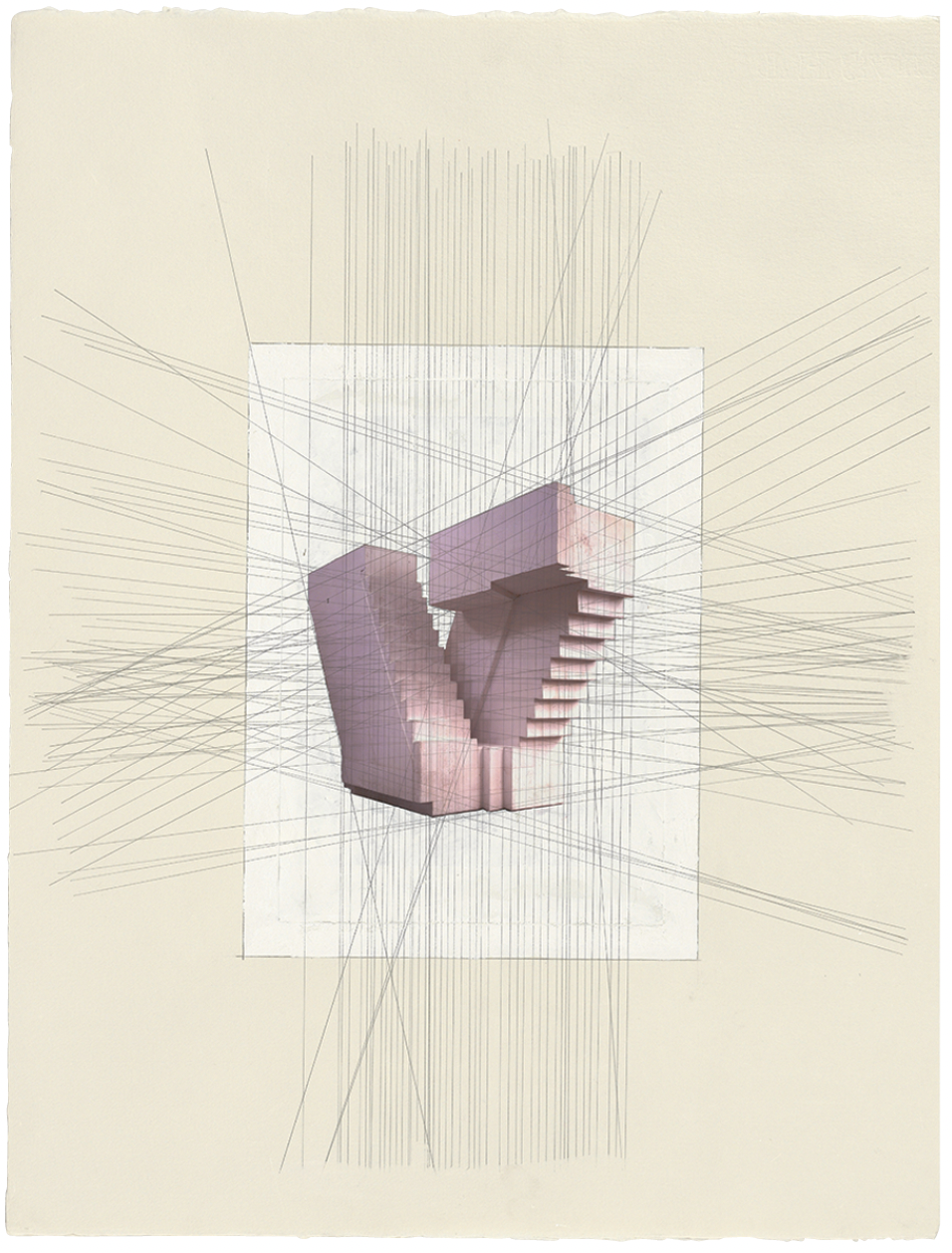

Rachel Whiteread, Stairs, 1995, correction fluid on black paper, 11 5/8 x 8 1/4”. Photograph: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection. Courtesy the artist and The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

By juxtaposing groups of drawings with the artist’s sculptures of related objects, Pesenti provides an understanding of the vital interplay between Whiteread’s use of the two media. For example, a wide variety of drawings of herringbone and brick-patterned floors—ranging from precise to expressionistic, plans to three-dimensional views, isolated sections to an overall pattern spread to the margins—created over a nine-year period, are installed around a stunning sculpture of an aluminum cast of a floor cut into 36 abutting squares. The sculpture is less like the minimalist geometry of Carl Andre than a very feminine mapping of a scarred but vibrant quotidian terrain drawn onto the flat surface. In the drawings that accompany the mattress sculpture, Untitled (Double Amber Bed), 1991, the medium sits like a heavy burden on the paper, which ruffles around the image as if around a sculptural object.

Two of the very few figurative drawings in the show, Heads, 2000, and Ripple Head, 2000, take an aerial—or, perhaps, God’s eye view—on the human head. They explore its formal properties, but also seem to imply that this most cerebral of artists is pondering the casting not only of the objects of her thoughts but also the cranium as a vessel for thought itself. Coinciding with a potential project for St. Paul’s Cathedral, these drawings combine her exploration of Renaissance perspective with the asymmetrical concentric ripples of a finger dipped into the waters of a baptismal font. She is literalizing the metaphor that she has used so exhaustively: the house as container of human lives. Pesenti injects an added curatorial frisson to these images by showing them adjacent to the drawings, notebooks and model relating to the artist’s Holocaust Memorial for Vienna, which cast the inner edge of a library as an homage to the lives and learning that were lost to unspeakable horror. Drawings of a rosette that is cast on the ceiling of this cubic sculpture, and which remains unseen by all but those observing it from above, refer strongly to these two heads—and their God’s eye perspective—enhancing the tomb-like quality of her memorial.

Drawings relating to large-scale public sculptures, such as Water Tower for New York City and the Trafalgar Square Plinth, precede those in the final gallery relating to Embankment, Whiteread’s monumental installation in 2005 for the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. These are collaged images of boxes—ready- made voids for life’s baggage—placed artfully on the page. Boxes, 2005, an array of several dozen brown, blue, pink and white cartons, evokes a strong sense of perspective with small objects being engulfed by an enormous space. Hall, 2005, a sculpture of plaster box forms stacked beneath, beside and on top of a small wood table, is shown with the drawings. The sculpture is playfully self-referential and, from a curatorial perspective, provides a nice symmetry with Flap from 1989, displayed in the first gallery, which monolithically casts the underside of a wood table with one leaf resting on the plaster.

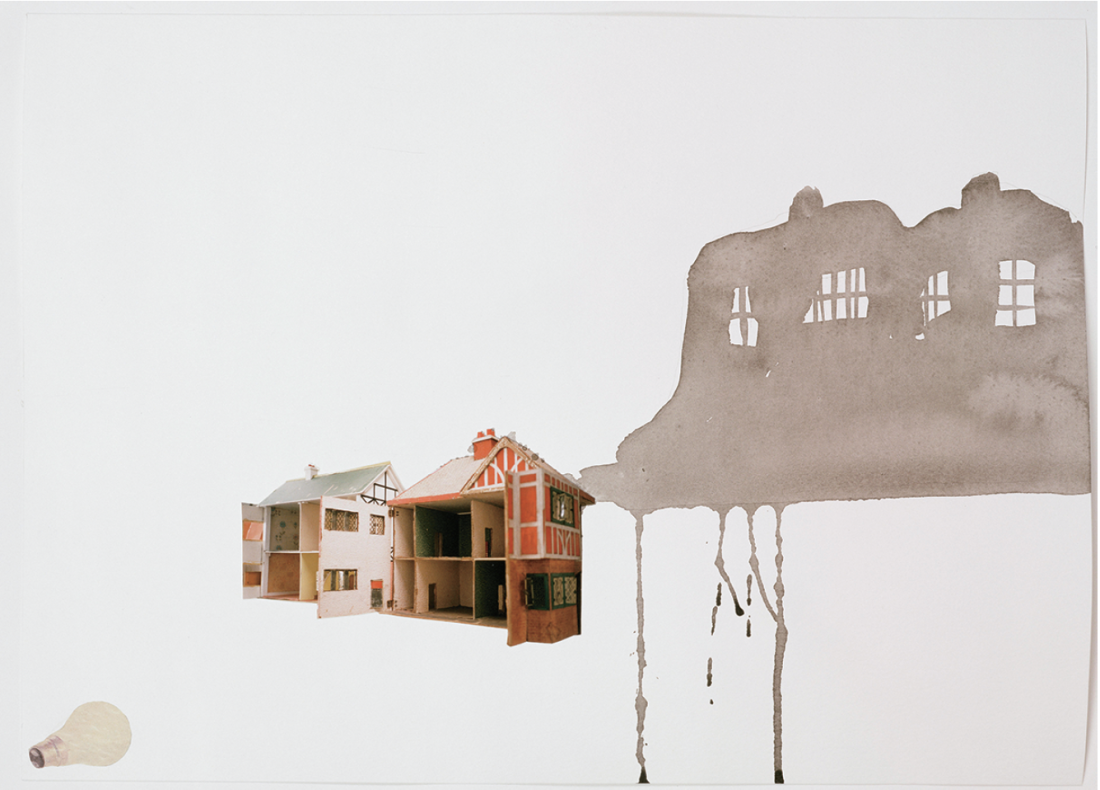

Rachel Whiteread, Study for “Village” — 1st, 2004, ink, pencil and collage on paper, 11 13/16 x 16 3/16”. Photograph: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd. Private Collection. Courtesy the artist and The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

This curatorial symmetry highlights the ways in which the Embankment drawings seem to straddle a transition to a body of work that departs from a focus on the casting of singular objects and, instead, are exercises in accrual and distribution of multiple objects in space, something that ties her sculpture practice closer to her drawing practice. In what feels like a three-dimensional sketchbook, Whiteread has filled a vitrine with over 200 objects—glass orbs, twigs, shoe forms, miniature furniture, skeins of thread—that are presented on three long shelves. Up close, the vitrine is a cabinet of wonders. Contemplated from a distance, these objects seem to describe the flatness of space in the picture plane, inverting the normal relationship between sculpture and drawing.

In the final gallery, Study for Village – 1st, 2004, a drawing that relates to a sculptural installation in which the artist created a village out of her 200-piece dollhouse collection, brings together many themes in Whiteread’s work. In it, an image of a light bulb is collaged onto the lower left corner of the page. Diagonally above it is a collaged grouping of dollhouses, diagonally above that is an ink drawing of the massing of the dollhouses below. The ink dribbles down the page, as if putting down roots to keep this ephemeral-looking image from floating away. It is plausibly the looming, imaginary shadow of the houses created by the imaginary light bulb or, perhaps just as plausibly, it is the houses dreaming of themselves, further animating Whiteread’s engagement with the imaginative life of the domestic space that was so startling when House vaulted her into the public consciousness in 1993. ❚

“Rachel Whiteread Drawings” was exhibited at The Hammer Museum in la from January 31 to April 25, 2010.

Susan Emerling is a writer living in Los Angeles.