Rachael Tycoles

There is an unexpected, sometimes uncomfortable beauty to “Passages,” a new series of paintings by Winnipeg artist Rachael Tycoles. Exploring oil refineries and rural seed factories, urban warehouses and waste grounds, Tycoles brings the viewer face to face with the suppressed visual history of the industrial landscape.

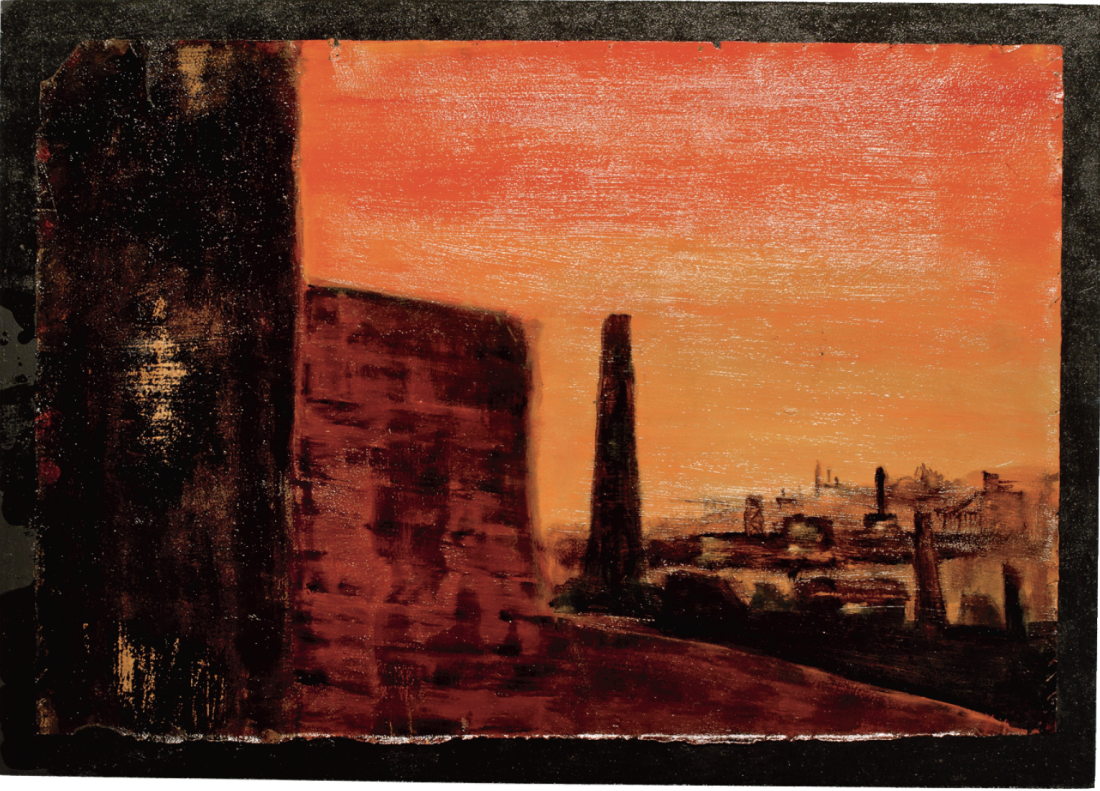

There’s a weight to these works, a tough physicality. The oil paint is textured and thick: Tycoles adds tar and asphaltum and sometimes copper leaf. She uses intense colours like teal and violet, carmine red and chrome yellow, offset with a browny-black so gleamingly deep it looks like it’s still wet. She favours simplified shapes, often Cézanne’s cylinder, sphere and cone, worked into solid, balanced forms. There’s a palpable beauty to these paintings, but Tycoles’s subjects aren’t ones that we generally read as beautiful. She depicts storage tanks and rail yards, silos and smokestacks, leading to a sometimes tense standoff between style and content.

Tycoles’s landscapes are neither the dark satanic mills of the Romantics nor the shiny mechanical utopias of the Futurists. Instead, Tycoles sees these industrial structures as crucial markers of working-class history and its legacy of labour, struggle and community. According to Tycoles, many people simply don’t see these overlooked, undervalued sites anymore. Some of the show’s subjects are taken from St. Boniface, the neighbourhood that surrounds La Galerie du Centre culturel franco-manitobain, but it would be hard for most people to place them. The picturesque ruin of a 1906 cathedral is the French Quarter’s most recognizable architectural icon, but scrubby rail lines and rundown factories—signs of the manufacturing and transport infrastructure that underpinned the growth of 20th-century Manitoba—don’t have the same cachet. For Tycoles, this is part of our culture’s squeamish reluctance to connect with the blue-collar industrial realities that have formed many of the material facts of our lives.

Rachael Tycoles, Elsewhere, 2011, oil tar on paper, mounted on wood, 24” x 17”. Photograph: Larry Glawson. Courtesy the artist.

While Tycoles has been influenced by painters from Goya and Turner to Monet and Sheeler, she has also cultivated an interest in photographers like Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher, German artists who catalogued a disappearing industrial landscape and landmarks of functional architecture. Currently, Tycoles is the only painter involved with Industriekultur-Fotografie, a mostly European group of heavy-industry junkies who photograph collieries and gas engines, blast furnaces and turbines, lime kilns and steel works, textile factories and dockyards. Members depict working sites as well as the derelict, rusted-out remnants of old sites, documenting the power and the sheer, massive physicality of these structures in the face of an increasingly disembodied and digitized information age.

Tycoles, who studied at the University of Manitoba and the University of Cincinnati, has spent decades photographing industrial sites all over North America. She uses this photographic record as a tool, but her paintings merge documentary evidence with past experiences to become evocative memory landscapes. Tycoles grew up in The Pas, and as a child often rode the rail lines in the west and the north with her father, who worked as a train engineer. (Her grandfathers, her father and her uncles were railway men, and Tycoles herself has worked washing down railcars.) She remembers being fascinated by mining sites and grain elevators, silos and water towers. (One scene especially, a rail yard across the street from her elementary school, stuck in her head. She painted it from memory in 2007, having not seen it in over 30 years.) Tycoles remembers, also, watching many one-industry towns turn to ghosts as North America’s economy shifted away from its historic manufacturing base. In Hinton, Tycoles paints an Alberta community that has stubbornly survived incarnations as a railway town, a mining town and a pulp-and-paper town. In her painting, it shimmers like a mirage in a hillside of white pines.

Some of Tycoles’s paintings depict robust, hard-working sites, white silos glowing behind a screen of trees or a nocturnal panorama of towers, trestles, stacks and cranes, lit up with the heat of activity. Other sites seem sluggish and slow, bypassed by the fast-moving new information economy, on their way to becoming post-industrial detritus.

Tycoles sometimes isolates single elements—the metal bracings of a water tower, for example—in medium-sized paintings, but she tends to tackle her biggest subjects on a small scale, sometimes a very small scale. Many of her multi-element industrial landscapes are narrow bands of intense pigmentation measuring less than 14 cm high. Panorama features a long, low prairie horizon broken by the rough, smudged, moody outline of some kind of industrial facility. The site’s work is intense but obscure. In contrast to the large-scale industrial sublime favoured by artists like Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, the tone here is intimate, enigmatic, maybe a little tender.

A searching examination of our relationship with the ignored industrial underside of our culture, Tycoles’ work is a tangible, tough-minded elegy for a passing age. ❚

“Passages” was exhibited at La Galerie du Centre culturel franco-manitobain, Saint-Boniface, from June 23 to July 30, 2011.

Alison Gillmor is the Pop culture columnist for the Winnipeg Free Press and often writes on visual arts and film.