Quilt World

Rosie Lee Tompkins and the Ordinary Sublime

I have always loved flea markets. Over the course of my life, I’ve haunted them far and wide, from palm-lined beach fronts in Los Angeles to rubble-strewn lots on New York’s Lower East Side, from abandoned military bases in Poland to shipping containers on windswept steppes in central Asia. I’ve browsed just about everything imaginable in flea markets: old military uniforms and medals, clothing and jewellery from bygone eras, Kalashnikovs and hand grenades, fluorescent velvet paintings and elaborately embroidered quilts. The collective unconscious of cities, flea markets are the kingdom of stuff that has been shunted off to garages and basements, and obsessive hobbies with no certain final resting place. I love flea markets, not because I expect to find anything of value or even collectible but because they are so democratic. They have no real gatekeepers, they offer no status, they have no world view or governing ideology. Yet occasionally they do contain something of transcendent power and beauty. To feel the shock of beauty of that kind, you have to be open to it, you have to peel away the layers of assumptions and expectations that most of us carry about beauty and art.

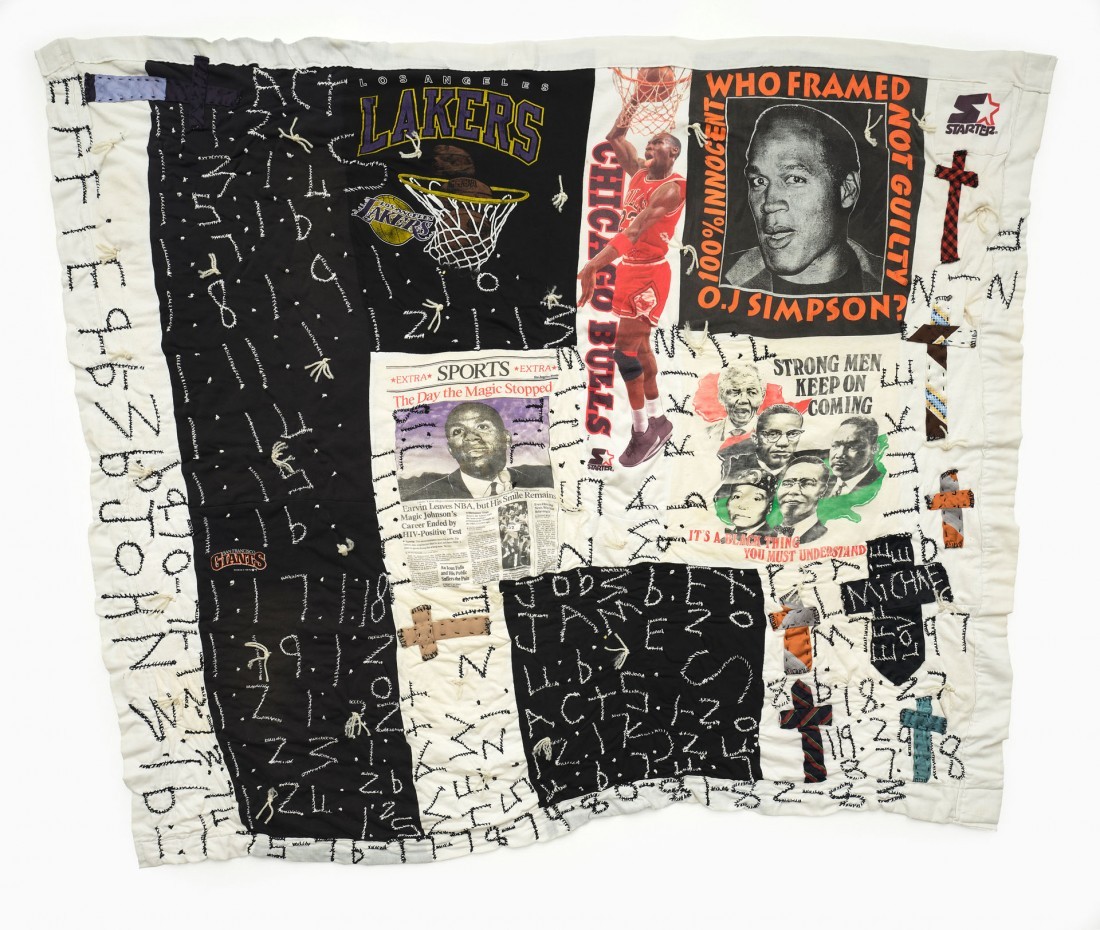

Untitled, c. 1996, found and repurposed cotton T-shirts, found and repurposed silk or polyester neckties, cotton knit, acrylic yarn, cotton embroidery, polyester knit and polyester backing, 61 x 71 inches.

It was in a flea market in the East Bay across from San Francisco that eccentric psychologist, erstwhile designer and obsessive collector Eli Leon encountered African-American improvisatory quilt making, and the artist and quilt maker Effie Mae Howard, who would eventually become known as Rosie Lee Tompkins. Over time Leon packed his modest bungalow in Oakland, California, with literally thousands of quilts by African-American women, but the prize of his collection were the quilts of Rosie Lee Tompkins. Leon may have been almost a hoarder, but he recognized that this woman from Arkansas who had left the Jim Crow South in the late 1950s as part of the Great Migration and sold quilts for extra cash was, in fact, a significant artist. A great artist, full stop. Eli Leon became something of a scholar of African-American quilt making and curated exhibitions in which he introduced these quilt makers (they would typically be looked upon as “folk artists”) to the broader public as significant artists. He introduced Rosie Lee Tompkins’s work to chief curator and museum director Lawrence Rinder, who included her quilts in the 1992 Whitney Biennial. By the time of his death in 2018, Eli Leon had donated his vast collection—over 3,000 quilts by more than 400 artists—to the Berkeley Museum of Art. “Rosie Lee Tompkins: A Retrospective” at the Berkeley Art Museum was scheduled to be on view through December 2020 but is on hiatus due to the coronavirus. The exhibition was curated by Lawrence Rinder, co-curated by Elaine Y Yau.

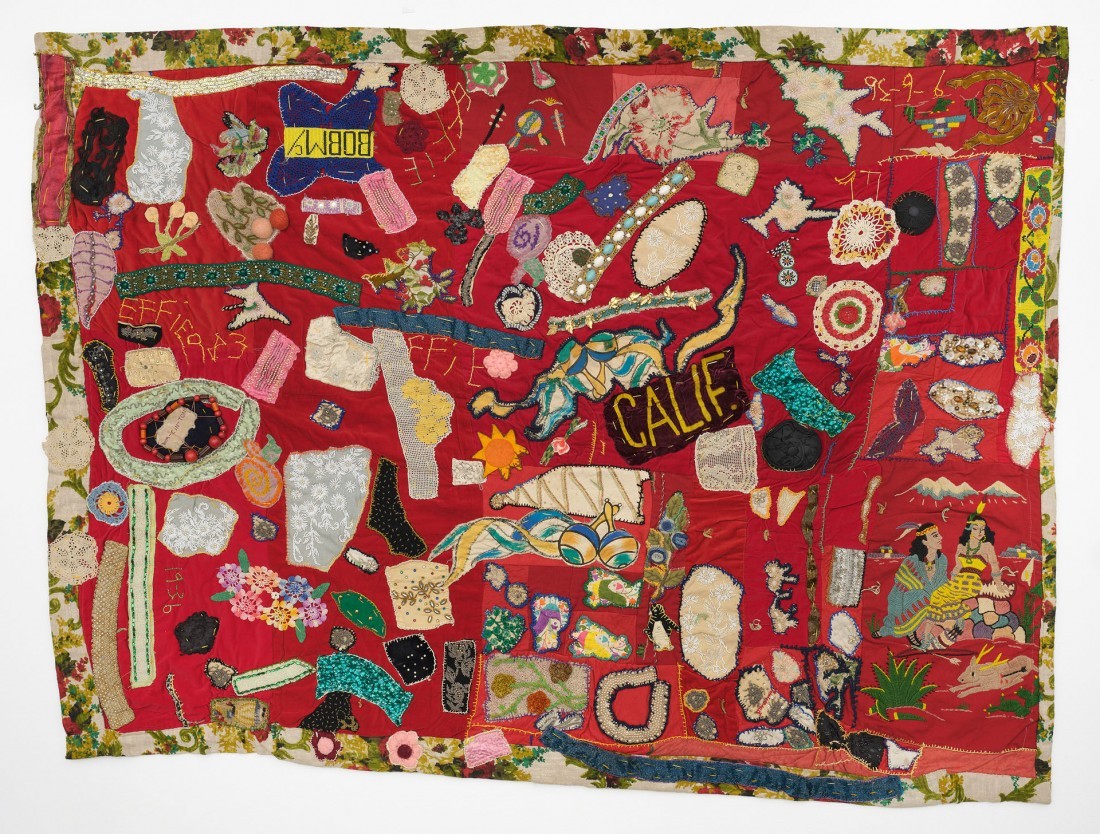

Rosie Lee Tompkins, Untitled, 1968, 1982–83, 1996, cotton, felt, wool, velvet, velveteen, found and repurposed embroidered fragments (variously decorated with chenille, wool thread, needlepoint, shisha mirrors and other materials), crocheted doilies, silk crepe, decorative trim (with beading, sequins, faux pearls, leather, rhinestones and other materials), hand-painted velvet, cotton thread embroidery and printed drapery, 57 x 75 inches. All photos courtesy The Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

It’s difficult now to fully imagine what it was like to see Rosie Lee Tompkins’s quilts for the first time—not on a museum’s clean white walls but draped over a card table in a flea market or spread out on a couch in a living room. Though far less exotic, I imagine it must have been a little like hearing Robert Johnson on a Mississippi street corner or in a juke joint in the 1930s: you would be startled, and even baffled, by the sudden and unexpected presence of something profound. Her quilts are gorgeous. They are also incredibly personal but at the same time almost ordinary, fashioned as they are from the materials that could be found in a flea market. The more you look at them, the more you linger, the more sublime and fathomless they feel. In one, for example, made from pieces of velvet and faux fur, dark rectangles are scattered across deep sky and sea blue, all of it framed by warm, earthy red and yellow shapes that evoke landscapes and buildings. This quilt is, in a way, a private altar. Its edges suggest the contingencies and sheer business of daily life with its trips to and from work, its grocery stores and laundromats, churches and schools; but the quilt’s rapturous blue centre, deep and sensuous and not wholly formed, serves as a kind of entranceway to heaven. Rosie Lee Tompkins was a deeply religious Christian, and this quilt is religious, with powerful spiritual resonances. People don’t just want to be redeemed and live forever; they want to touch grace and heaven here, in the messy hurry and uncertainty of mortal life. Rosie Lee Tompkins’s aren’t just beautiful objects that you want to contemplate; you want to touch them, lie down on them, be part of them, feel whatever it is radiating up through them.

…to continue reading the article on Rosie Lee Tompkins and the Ordinary Sublime, order a copy of Issue #155 here, or Subscribe today.