Questioning Photography

Ashley Gillanders keeps wondering about photography. From the time she saw an exhibition in 2014 at the International Center of Photography in New York called “What Is a Photograph?” she has been asking herself the question posed in the exhibition’s title. Curated by Carol Squiers, that show featured 21 emerging and established artists, including Alison Rossiter, Eileen Quinlan, Travess Smalley and Owen Kydd, and inquired into the myriad directions that photography had taken since the 1970s. Gillanders saw the exhibition during a residency between her undergraduate work at the University of Manitoba and going into the graduate program at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She had been a self-described traditional photographer who had been using both large-format film as well as a digital camera, but the ICP exhibition coincided with a dissatisfaction she was feeling with the medium: “I became bored with the process because it didn’t physically involve my body. Working with Photoshop wasn’t satisfying this need to become more physically involved in the work.” The series that came out of her reassessment were photographic sculptures in which she cut and glued and worked with her hands to “make” the photograph after it had been taken. These hybrid photograph/sculptures were shown in “Methods of Preservation” at the University of Winnipeg’s Gallery 1C03 in 2016. The exhibition itself was productively confusing; the images-cum-objects were displayed in Plexiglas cases and on wall ledges that allowed the work to occupy simultaneous conditions of science and art. They read most convincingly as sculpture.

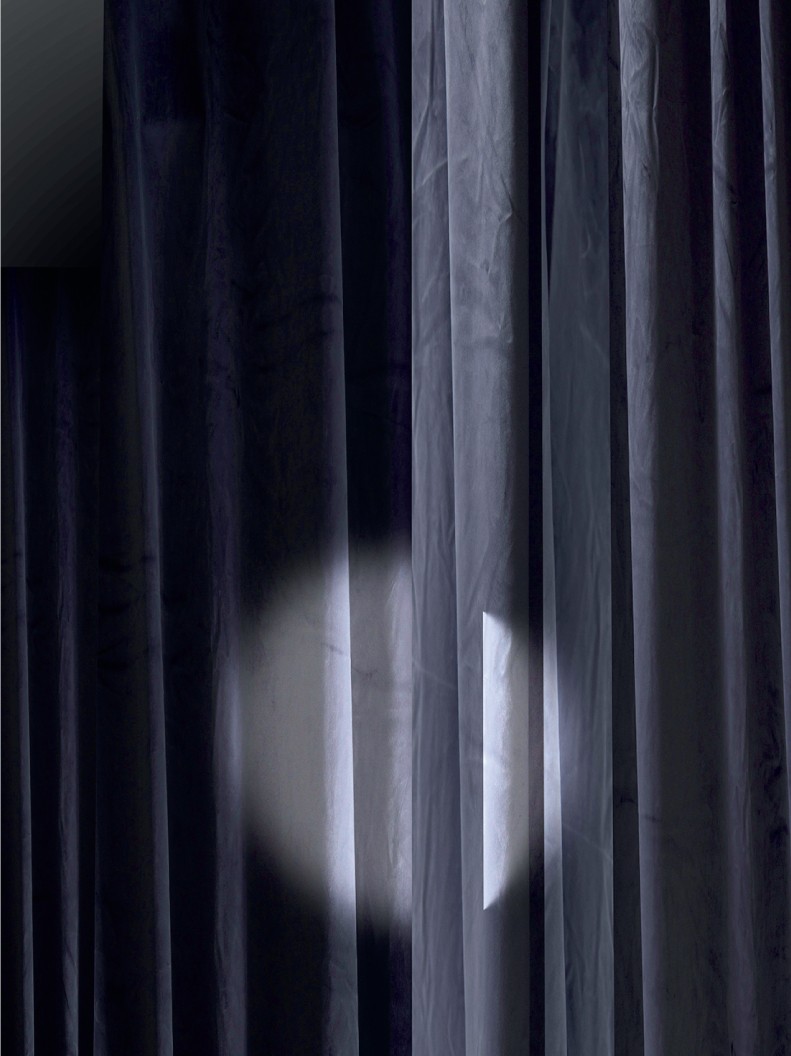

Ashley Gillanders, installation view, “Mirror with a Memory,” 2020, Platform Centre for Photographic + Digital Arts, Winnipeg. All images courtesy the artist.

Her recent solo exhibition at the Platform Centre for Photographic + Digital Arts in Winnipeg, called “Mirror with a Memory,” shows the range of her inquiry into the vexing question of “What is a photograph?” She presented work that came from two sources: a photograph from a camera that documented objects that exist in space and camera-less images that employ a computer program to make space exist. She is the photographic offspring of Thomas Demand (an artist who has been a major influence) and Canadian Jessica Eaton. The two approaches to image-making reflect Gillanders’s interest in conducting a conversation about the space between the physical and the virtual; the subject that gives her the most room to conduct that conversation is the stage. “It is the place where reality and non-reality and fiction and non-fiction are explored,” she says, “and the curtain acts as the space in-between.” The Maya program she is using is mostly for 3D animation, but she realized it had potential for creating still images. “The beautiful thing about this program is that it functions like a camera would in the studio,” Gillanders says, “so I’m creating this image, I’m lighting it, I’m choosing the material for the fabric and then I’m making decisions about the camera position, setting the aperture and framing it the way I would with a film or a digital camera.”

Untitled (green fabric), 2018, archival pigment print, 30 x 40 inches.

The images are incredibly attractive. They register a strong sense of theatricality; the folds and creases in the curtains are suggestively without volume; the shadows are flat spaces and not overlapping layers. The “Views from the Apron” series is realized through colour sequences—yellow, blue, pink and black—and suggest various perspectives on dramatic thresholds: a glimpse to what would be backstage in the blue variation; a voluminous fold in yellow; and in black, a spotlight suggesting a place where an actor or dancer might emerge for a bow.

The physical exploration in her work occurs in the relationship between the sculptural maquette and the large photograph in It’s a Poor Sort of Memory that Only Works Backwards, 2018. The shift in scale from the miniature model to the imposing 60 x 80-inch archival pigment print is dramatic, as well as humorous. “You see this large and commanding presence and then you turn the corner and see a tiny, crappy maquette. I was looking for this sense of disappointment,” she says. In this piece she gets closest to Thomas Demand, although in her case both the source of the image and the image taken from it are retained.

Gillanders also began flocking the frames of the digital images. It involved rayon fibres with colour-matched adhesive applied with a flocking pump, a process that allows only 15 minutes before the adhesive firms up. What made the flocking attractive was its way of making the digital images physical. “For me,” she says, “it was an extension of the fabric being represented.”

Views from the Apron (black), 2019, archival pigment print, 24 x 33 inches.

Gillanders’s perplexing relationship to photography is ongoing: “I am using it to explore places that don’t actually exist; there is no light involved; there is only data. So I actually ask myself whether I should even call what I make photographs. Maybe a better word for them is images.” Whatever she calls them makes little difference to their seductive effect. Untitled (green fabric), an archival pigment print from 2019, shows a wrinkled green cloth on top of a table, at the back of which rests a mirror. The mirror shows a portion of the fabric, but in the reflected surface it lightens to the point of disappearance. A mesmerizing image, it suggests everything and nothing at the same time, as if it were a scan of consciousness. Gillanders would say it is what memory looks like.

For all her movement back and forth between the virtual and the physical, she stays true to an abiding interest: the way the images look. “I can’t deny that I think these curtains and this fabric are all so beautiful. For me, a lot of it is just about physical pleasure.” ❚