Quarles Sum: Christina Quarles Makes Painting Add Up

There doesn’t seem to be anything that Christina Quarles won’t do to make a painting. She is intent on applying various tools, techniques and open-endedness to help in the construction of her paintings. The possibilities are augmented by the facts of her own autobiography; as a queer, cis-gendered, biracial woman, she has a richly layered identity on which she can draw. Her own assessment is that she is involved in “the ever-evolving recontextualization of the self.” That sense of focus has determining consequences for the look and content of what she produces. As she says in the following interview, “In my paintings I try to find a way to include as much as I possibly can. They are not minimalist paintings.”

A work like E’reything (Will Be All Right) Everything, an acrylic on canvas from 2018, proves the density of its naming. Quarles’s paintings often take their titles from sources in popular culture, especially music; Don’t Let It Bring Yew Down (It’s Only Castles Burnin’) riffs on Neil Young’s 1970 anthem about rescuing hope from despair, and To Where You Once Belong (Get Back) reverses the opening line of The Beatles pop tune about a character who “left his home in Tucson, Arizona / For some California grass.” The connections between the songs and the paintings remain mysterious.

In the case of E’reything (Will Be All Right) Everything, it’s hard to know if the compacted composition echoes Bob Marley or Infinity Song, or neither, but what is knowable is that the “everything” the song lyric alludes to is in the painting: the intersecting arms, legs, feet and hands creating rhythms that are both protective and oppressive, the mash-up of pattern and colour, the constant build and shift of surfaces.

Quarles is aware that her way of working necessitates finding a way to balance “excess” with “moments of clear legibility.” In the following conversation she addresses her “knotted sense of detail”; it is a method of rendering the figure that can make it difficult to determine which leg belongs to what person and, in paintings like Don’t Let It Bring Yew Down (It’s Only Castles Burnin’), there are more hands and feet than there are corresponding bodies. The confusion over body parts only makes the painting more attractive. It was one of six paintings Quarles made for the Venice Biennale in 2022. Included among the six-pack was Gone on Too Long, 2021, a work that embodies all her orchestrated strengths. The “choreography of brushwork” results in a stunning painting.

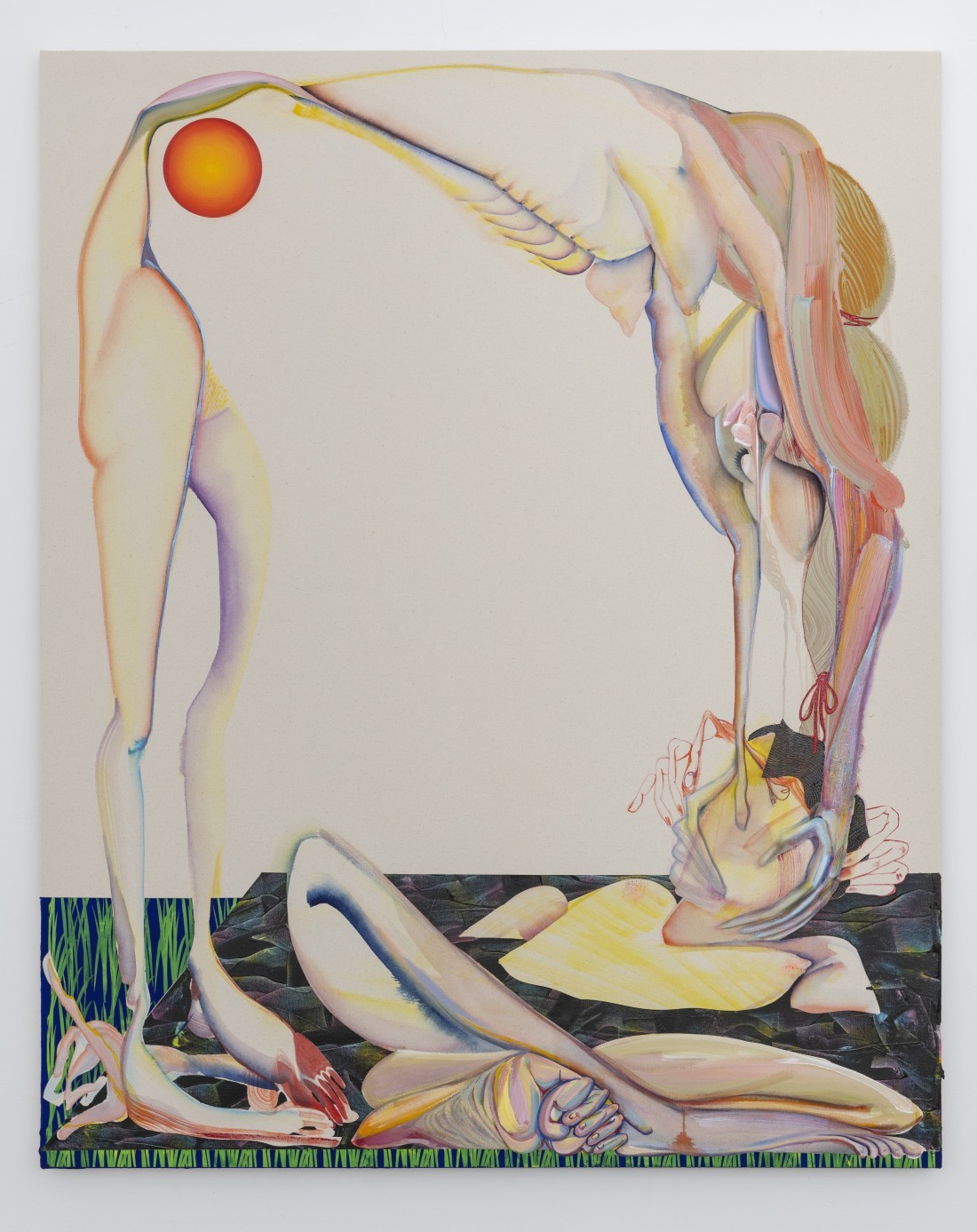

Christina Quarles, Tha Nite Could Last Ferever, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 213.4 × 182.9 × 5.1 centimetres. All images courtesy the artist, Pilar Corrias, London, and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Tha Nite Could Last Ferever, 2020, raises the figurative temperature even higher with four bodies in various stages of tactile engagement; the woman on the right hand-side of the painting uses one hand to caress the back of one figure and the other to cup the head of the figure behind her. That figure’s orange body has a bubble butt and an elasticity that allows it to occupy more space than seems possible. There is something suggestively carnal about this scene; it’s a night sky but a hot beach. In Pried/ Prayed (Hard Rain Gon’ Come), the touching among the three figures occurs in a place where the hard rain from Bob Dylan’s ballad has already arrived. Like Tha Nite Could Last Ferever, the women’s erect nipples and the dance-hall stretch of hot pink leg up the entire left-hand edge of the painting are full of sexual promise.

But her work is not all libidinal teasing, and what Quarles calls “that seduction of looking”—Tha Devil’s in Tha Details, 2019—turns the body of a willowy blonde into an archway, and the delicacy of her face and her irresistible black eyelash is almost religious in its serenity. In affirming that intimacy can be quiet, the painting tells us that not only is the devil in the details but so is the angelic.

Christina Quarles’s most recent solo shows are “Collapsed Time” at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin until September 17, 2023, and “Come In From An Endless Place” at Hauser & Wirth in Menorca, Spain, until October 29, 2023. She will also have a solo exhibition at Pilar Corrias in London, UK, from October 9 to December 22, 2023.

The following interview was done by phone to the artist’s studio in Los Angeles on July 27, 2023.

Border Crossings: Let me ask a question that combines numbers and invention. You produce work at an astonishing rate and you seem endlessly inventive. Have you figured out the source of that imaginative productivity?

Christina Quarles: Working in the studio is an interesting process because there’s no level of confidence you can reach where you feel you’ve mastered it and can coast on, moving forward. There’s a worry that, oh no, what if I’ve forgotten how to paint? and it doesn’t go away. Hanging onto a little bit of anxiety keeps you yearning to come up with an inventive way of looking-through-making that keeps the flow of inspiration going. I’m also easily bored, so I do something in each painting where I’m not sure how it’s going to turn out.

In your conversation with the writer Maggie Nelson, you talked about what you called “productive failure” in the studio. How does that work?

What interests me in each painting is the idea of my own wingspan, whether that’s a physical wingspan in the gesture itself, or literally what I’m capable of doing. I find that butting up against the limit of my ability is a place where I can really push myself and tweak what I’m doing to make the painting successful. Usually, it’s an unexpected moment that breaks me out of how I initially thought I would resolve the painting, and that keeps it interesting for me and, I hope, interesting for others.

I’m curious about the degree of anxiety that accompanies the act of painting. There is the image of the agonized Ab-Exer, almost always male, suffering an existential crisis as he ponders the blank canvas. You told Nelson that coming to a blank canvas is your greatest joy.

I find a lot of freedom and possibility when I’m approaching a blank canvas. For me, the beginning part is the time when there’s nothing to solve. It’s all open-ended. My favourite pieces are ones that reach this intense area of struggle halfway through, and what marks the completion of the painting is when that struggle gets resolved.

You said that painting sets up a series of problems or puzzles that need to be figured out. Do you have to set up the problem or devise the puzzle, or are they there simply because painting is problematic?

I’m certainly not trying to make it difficult. My speed of mark-making makes people think that I could easily make a lot of paintings, but the reality is that getting to that point of struggle within a painting and then breaking through it is an emotionally taxing process. The incredible thing about paint is that you’re working with an idiosyncratic physical process and through a strange material alchemy. You’re contending with this very technical side of artmaking, while also thinking through what you physically and emotionally want to get across on the canvas. You’re always up against the physical restraints of the material. Working with both image and material inherently creates an interesting puzzle.

_Everything_copy_2_1100_1380_90.jpg)

E’reything (Will Be All Right) Everything, 2018, acrylic on canvas, 101.6 × 127 × 7.6 centimetres. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

You love the beginning of the process, so how do you proceed? Does proceeding continue the joy or introduce some other emotion with which you have to contend?

The entire process has things that keep me engaged or else I would shift my process. The beginning of a painting is always quite physical. I spend some time looking at the blank canvas itself and imagining a possible composition or a choreography of brushwork. Then I lay down a first mark and the progression is from large tools to small tools. I’ll usually start with larger stain brushes and do big gestural moves that activate different quadrants or zones of a canvas. Then I’ll spend a lot of time looking at what I’ve done. It’s the zone artists talk about where they lose track of time, and I find it a tricky zone to be in. On the one hand you can activate this inventive and exciting flow state of working, but on the other hand you can fall into routine or habit. I try to interrupt that process and spend time really looking at marks that were intended to be certain parts of the figure or certain poses or certain compositions. If it was supposed to be the back of a figure, it might be more interesting as the front of a figure; or maybe it’s more interesting as negative space between two figures. That process of looking shifts the direction. Looking at what’s actually happening versus what I want to have happen provides me with a new set of intentions. Then the whole process falls into a completely different stage when the figures start to develop. That’s when I’ll photograph the work and bring it into the computer and play around with Adobe Illustrator. What comes forward is a mathematical, digital way of thinking through image-making. I’m playing around with the patterns and architectural elements. Then I reintegrate a digital image through the physical process of laying it down on the canvas and making it into a stencil, which I fill in by hand with painted brushstrokes.

I want to pick up on the visual effect of your methodology. The painting Held Fast and Let Go Likewise (2020) has a remarkable compression.

A painting like that clearly moves from a macro way of working to building up the forms and the textures. That leg starts with the hip ball joint in the dead centre of the canvas, and then this long brushstroke leads into a foot that stops bluntly because of the canvas edge. I immediately will put something like a big orange brushstroke across half of the canvas, so it’s no longer a precious, blank, pristine space. The initial purpose of that orange brushstroke might have been a much shorter body, or it might have been an arm. There are different possibilities for what that could have become. But the process of looking is what leads to the central configuration of different body parts having this knotted sense of detail. So in Held Fast and Let Go Likewise there’s a central face that’s quite built up with texture, and that’s where I move into stencils. All those moves get added to articulate different figures that can read as single bodies moving through space, or as double bodies. I look at something and think these are going to be the arms, but as I start to paint, the arm could turn into the boob of another figure. Sometimes body parts will morph into being a body part shared by multiple figures. I’m building from one thing to the next and then I’m observing the forms that are starting to take. Bringing it into the computer changes the scale of what I’m looking at. In real life a very large painting can appear on the computer as only a few inches tall. It sounds obvious but what it creates is this zoomed-out way of looking at the composition.

You have insisted on an intimacy determined by the scale of your body. Does changing the scale register in Adobe Illustrator affect your emotional reaction to the work in any way?

So much of the work is bound to my own physical scale, and yet so much of what I think about when painting the figure and these environments is this psychic space, this space of interiority that is not an externalized physical sense of self. It’s about the ways that our physical bodies interact with elements that are on a very different scale, like architecture or social structures or histories and identities, or ways of seeing. Even though these things include a lot of references to individual bodies, they are not necessarily at a physical body scale. The use of Illustrator is really fun because fundamentally it is an infinitely scalable computer program. Its whole existence is to be vector-based and not pixel-based, so it’s not determined by any scale. I’ve had this fantasy of working properly on the computer, but then I still use my laptop and the little trackpad to draw things. I have a vinyl plotter now that can perfectly cut my marks in the computer to make these precise stencils. It’s this really tiny scale that I can blow up to be a much larger scale, but because it’s all done with stencils and then paint application and the removal of the stencils, it’s another chance to have these two scales meet. Then I can use a gestural brushstroke to fill in the stencil, so it’s a gesture that’s at a shoulder scale to create an image of a gesture that’s more at a finger scale.

Tha Devil’s in Tha Details, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 157.5 × 127 centimetres.

Your paintings encourage two reads; one is looking in and the other is being in. Looking in is what I do as a viewer and being in is where you are as the maker. Do you distinguish between those two reads of your painting?

It’s an interesting idea to differentiate between looking in and being in. A lot of the times when I speak about my work, I’ll talk about the difference between looking at a body and being within your body and looking out into the world. I’m interested in portraiture occupying the space of being within your body and looking out. Of course, it is also an interaction with the medium of painting where you are looking at an object. A lot of the decisions that go into making the work are as a viewer, in addition to being a maker. I hope that some of that idea of being in can also translate to the process of looking at the pieces. It’s challenging because it changes the position of the person standing in front of a painting. It is this place where you simultaneously have to contend with what it is to be in your body and to know your sense of self but to also be aware that what you are internalizing and projecting is something that’s being observed and interpreted by other people. Then your next set of moves or decisions or ways of understanding yourself is going to be based on this externalized input. What I’m hoping to achieve with these images is that idea of both looking in and being in. It’s something I try to think through in making the pieces.

The looking in is a compelling process. The paintings can be incredibly sensual and sexual and they work on the viewer in complicated ways. Do you set out to do that? Is your strategy one of seducing the viewer into the act of looking?

Not necessarily, although I think a lot can be accomplished by creating that seduction of looking. My ultimate goal is that people will spend enough time looking at my paintings to have an experience that shifts through the process of looking. I remember my goal in grad school was to find a way to clearly depict ambiguity.

Clear ambiguity is a lovely idea.

I didn’t want to make ambiguous images about ambiguity and I didn’t want to be confusing about it. I wanted to be really precise and direct. At the time I often confused ambiguity with the idea of being vague. Being vague is a lack of information, but the ambiguous is about an excess of information. In my paintings I try to find a way to include as much as I possibly can. They are not minimalist paintings. I really work on this area of excess but in that excess, I try to have moments of clear legibility. In the most abstract situations, and even when we’re looking at nothing, we try to find patterns, to find faces, we try to find the figure.

Sweet Chariot, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 182.9 × 243.8 × 5.1 centimetres. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

You have remarked that you were “tied to a very rigid tradition of how to render the body.” The rigid training may be there, but you don’t seem to have any governors on the way that you render the body. Is that a fair assumption?

I would take that as a fair assumption. Whether it’s from something that’s externally taught or something that is internally worked out, it takes a lot of practice to reach the stage of being able to feel ungoverned. I’ve found that many, many years of discipline and rigid formal training allow me to have a sense of inventiveness in my practice.

One of the things that interests me about your work is what I regard as containment strategies. The shape of the arc turns up repeatedly in your work. In Don’t Let It Bring Yew Down (It’s Only Castles Burnin’), the figure on the righthand side links arms with the woman in the centre of the canvas in what strikes me as a Cézanne gesture. Then Gone on Too Long has this beautiful leg that goes up the righthand side of the painting, and when it comes down to the bottom, you think it will resolve itself into a body, but it doesn’t do that. Instead, it becomes a hot pink line going across the bottom of the canvas. But both of those things, the arc of the two hands meeting and the leg stretching up and going across the composition, are containment strategies. They hold the eye inside the painting. Are those strategies of making?

I’m never consciously thinking “containment strategy.” What I’m thinking about is: How is this achieved in art history, and how can I achieve it in this single painting? I don’t love the idea of painters being intuitive because I think it creates, around painting, an idea of a mysticism that I don’t fully buy into. For me, it comes out of this internal core sense of how to make things. I think it is this idea of a scientific flow state. Your technical skill can be so well practised that proficiency allows more inventiveness to creep forward. I know a painting is complete when I’ll have areas where just a single line renders a form. There are certain things that are not materially determined that I’ll leave in a completed work. I’m aware that the painting is done when I can actively look at it for a long time and never arrive at an area where I feel I need to fix a problem as a maker, where I can stay active as a looker. It’s the activation of looking for a long time that necessitates these compositions and containment strategies.

Gone on Too Long, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 152.4 × 182.9 × 5.1 centimetres. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

You can suggest that a thigh has contour and volume, but then you can also render a foot as only a tracing of scratchy orange lines. Are those careful calibrations?

It’s from the background of a person who drew. I drew long before I painted, so I was always interested in contour lines. What painting has allowed me to do is to continue to emphasize the gestural contour line. I could be making one with a very thin brush and it feels more like a drawn line, or I could do it with a very thick brush and that gestural line becomes a full-volume foot because I’m still moving the tool in a linear thought process.

The paintings in the Venice Biennale seem to be more physical and sensual. Are they more about the body than some of your other paintings?

I don’t have a plan. I have a general idea, I see where it goes, and then through a process of observation, I speak back to myself about what I see happening as a thematic thread in an individual piece or in a body of work. That process also allows me to be receptive to what’s happening in my daily life, or culturally, or just with the things that are influencing me. The Venice work was made at the tail end of the pandemic lockdown, so Gone on Too Long was made right before I left town for the first time since the pandemic. I went to see my exhibition at MCA Chicago, but before that I had not left my house or had any break from making work. Usually, my breaks come in the form of going to install an exhibition, but in the pandemic, I just was working, working, working. As a result, the paintings were getting super-intricate and super-complicated. I ended up keeping Gone on Too Long because it was so needling and such a difficult piece to make. It was a time when my wife was pregnant, so we were also in a place of “body awareness,” coming out of this unique period of time. It makes sense that these paintings had a more bodily presence because so many of the patterns, environments and the architecture in them were inspired by what I was seeing in my daily life. At that point I’d been in my house for two years, so I was less interested in the environmental aspects and more interested in the physical aspects.

Am I correct in assuming there’s not much erasure in your painting, that it’s more about addition and accumulation than about removal? The process of what you call “becoming and unbecoming” is one that is essentially additive and built rather than subtracted and removed?

Yes. There is room for that within the planes that come in through the editing because those always happen after the figuration. If there’s an area that needs to be cleaned up or made more clear, then there’s an opportunity to do it. It’s adding a plane and there are usually large areas of raw canvas. There are also some areas that remain untouched. In the decision-making, even when it’s about removing an area of figuration by adding a blue sky, that’s still an additive process.

You have remarked that walking around your studio, or observing things in the street or in a thrift store, can be as influential as looking at art history. It may be a by-product of the fact that I spend my life looking at works of art, but anytime I look at a work of art, a prod of retinal memory takes over and I see other works of art. So I look at your shapely posteriors and Carroll Dunham comes to mind; I see the swirling white on blue lines in the lower section of Cut to Ribbons (2019) and I think maybe of Matisse but assuredly of David Hockney’s swimming pools; I see your Harlequin patterning and Picasso enters the frame. I can even detect echoes of Dali’s pneumatic, eroticized rhinoceros horns in certain of the intersecting and penetrating shapes in Tha Nite Could Last Ferever (2020), Cut to Ribbons (2019) and Day ’Fore Night (2019). What I’m commenting on is the way that a painting can carry the memory of earlier iterations in paintings by other artists. That must be the case for you as well?

Yes. It’s a question of distinguishing between an influence that drives the work and an influence that surrounds or supports the work. I always find the art historical references to be less about the drive and the conscious in-the-moment decision-making and more of the surrounding narrative to the work. It’s not the explicit goal of the pieces to make those references, but I am always observing my work and finding it interesting to have conversations with people about it. Even now I’ve written down some notes from our conversation. There are always things that are going to impact the next set of decisions that I make. If there’s a read of the work that I don’t love, or some art historical read that I feel is way off base, it’s something that I try to pay attention to. First, why do I have that reaction and, second, if it’s something that I don’t want to have in the work, what can I do to change that? But I don’t think it’s off base to have those references. I think we’re always referencing our own pool of knowledge. If you look at a lot of art history, then that will be the pool. The exciting thing about making art that becomes part of art history is that it’s going to be in dialogue with the things that come before and it’s going to change the read of your own work as well. I try to have my work embody a more complex read of eroticism, sensuality and intimacy. I want it to hold a place for a pleasurable version of those terms, and to also have moments that are mournful or sorrowful or violent because you can find aspects of intimacy in all those modes.

Christine Quarles, installation view, “Milk of Dreams,” 2022, Venice Biennale. Photo: Andrea Rossetti. © Christina Quarles.

You’ve pointed out that intimacy is not only about physical lovemaking. Wherever there is proximity, the possibility exists for some kind of intimacy. Any time a body comes into contact with another body, the intimacy that occurs can be good or bad. Do you have a darker read of your paintings? Some seem edgier than others. What is your view of the emotional register of the work?

It’s funny because I usually feel there is more a sense of mourning in the work. I usually tap into that place of grief or mourning. That is where I start from and it creates a need for moments of comfort. I am interested in these very intense moments happening in the painting and for there to be other areas where a figure is looking away or is distracted by something arbitrary or unimportant. Like a figure looking up at the corner of the painting, or looking at their hair.

You’ve got a painting called Sweet Chariot, which obviously refers to the gospel tune, but it also includes, as do many of your other paintings, a silhouetted figure. That figure can be either black or white; it can be a shadow or a kind of ghost. What function do those figures play in your painting? Do you think of them as different kinds of figuration?

They’re created in very different ways and they have different functions. So with the white figure and the negative-space figure in Sweet Chariot, both operate as a sort of negative space, one being literally the raw canvas with no application and material. But whenever I paint one of the black silhouetted figures, I always use a highly matte, super-pigmented paint called flashe, and because it absorbs so much light it becomes a more literal idea of a negative space. They are also both created through the use of stencils—the negative-space figure is masked out, so the use of a stencil emphasizes and defines the area of blank canvas, while the black solid figure uses a stencil to define positive space. In Sweet Chariot the line around the negative-space figure was added on with a brushstroke, but in other works that black silhouette is a figure devised on the computer. It’s made through a stencil and at a very different scale. The silhouetted figure exists in the way that the planes or the patterns exist, supporting and containing the figuration that’s happening in the canvas. It’s using a figure, but it’s still the head space because it’s being made on the computer. The scale of thinking it’s made at is about the totality of the composition, but it’s rendered as a figure rather than as an arch or a shadow.

Cut to Ribbons, 2019, acrylic on canvas, 243.8 × 139.7 × 5.1 centimetres.

The totality of the composition is different from narrative, isn’t it? Your paintings don’t add up to some kind of story.

I’m not particularly interested in narrative. I love narrative as a human being, but I’m not interested in my paintings’ having a fixed narrative read. When I make them, I am not trying to tell a specific story, but as I make them I am telling myself a story. I’m talking to myself as I make them, thinking, oh, this reminds me of this. And it’s that way of looking at the work and describing it back to myself that allows me to make the next set of decisions. I am starting to build a narrative as I make the work, but it’s not important that that narrative is legible to a viewer. The choices that I make are from a much smaller pool of options because I start to be like, “Oh, this scene is happening and then this thing is important about that.” Then it gets reiterated in the title. The reference in Sweet Chariot, for example, is to the gospel song, but compositionally I was thinking about this strange negative-space hammock thing. The vessel holding the figures and the ethereal location feel more like the idea of death in the gospel song “Sweet Chariot.”

_copy_1100_882_90.jpg)

Pried/Prayed (Hard Rain Gon’ Come), 2020, acrylic on canvas, 195.6 × 243.8 × 5.1 centimetres. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

I want to ask you about the way that you have rendered the woman’s body. There are other queer artists, like Nicola Tyson and Ambera Wellmann, who have consciously created a language of the body that becomes a language of female desire. I’m asking how much of your intent has been to create a language that belongs to you and your desire.

I think the goal of any artist, whether you’re a painter or a writer, is to find language that is your own, in your own voice. What’s important to me is that my voice be honest about my own experiences moving through the world, as a woman, a queer person and a multiracial person. Because a lot of what drew me to making work early on was a desire to find a way to describe aspects of myself that I didn’t feel were adequately described in existing language, whether verbal or written or artistic. I couldn’t readily see how I experienced all my various forms of identity and intersections of identity. I had to piece it together through a lot of existing things because there wasn’t one single thing I could go to. So finding specificity in my visual language is important. I make the work that I make to find a way to describe the specificity of my experience. But there’s this weird counterintuitive thing that I talk about when I do studio visits with grad students. We have an idea that it would be alienating if we were to be super-specific, and in order to be more generous and open and community-oriented, you should be as broad and as general as possible. But I found that with making art, it’s the opposite of that. If you are super-general and broad, that’s when you start to fall into clichés. But when you are super-specific and going deep into what interests you and into your own experience, that is when the work connects with a broad audience of people. All that is a convoluted way to say that I try to find my own language in my work, and it’s a language that reflects the specific and individual experiences that I have with the larger identity positions that shape how I move through the world. Queerness is one of them, as is being multiracial and being a woman. These identities never quite fit into any one category so they have to exist simultaneously in multiple and often contradictory experiences. ❚