“Prospect. 1 New Orleans”

Motivated by a desire to revitalize the local arts community and to draw attention to his adoptive city of New Orleans, still struggling to resurrect itself three years after Hurricane Katrina, curator Dan Cameron has brought together the work of 81 artists from 34 countries, including several native Louisianans, for “Prospect.1 New Orleans.” This vast international biennial is in turns moving, provocative and filled with moments of awe at what artists can create from the detritus of human and natural devastation. It is also an unsentimental look at what is certainly a vibrantly creative but grandly imperfect city. By placing the work in 25 venues across the city, from the inundated, impoverished Lower Ninth Ward to the high ground of the wealthy Garden District, Cameron forces the visitor to traverse the city and experience present-day, post- Katrina New Orleans in all its history, variety, inequity, urbanity, natural precarity, and resilience.

Adam Cvijanovic, The Bayou, 2008, flashe and latex on Tyvek. Installation view at Tekrema Center for Art and Culture as part of “Prospect.1 New Orleans.” Photo: John d’Addario. Courtesy Blue Medium, New York.

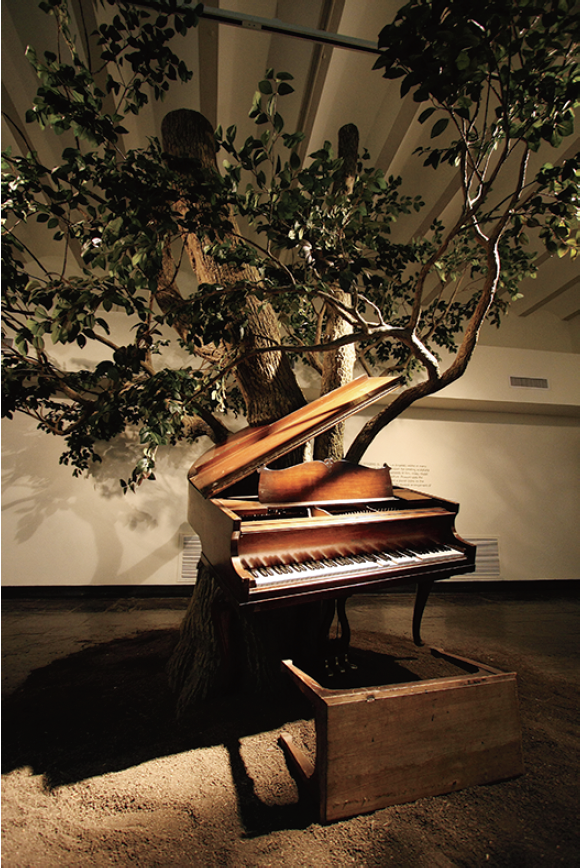

The bulk of the artists’ works is housed together in two large, centrally located venues—the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) and the Louisiana State Museum – Old US Mint. Standout pieces, such as a video by the team of Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, new paintings by Julie Mehretu, and mixed-media installations by Luis Cruz Azaceta coalesce around a theme of the instability of urban life and the uneasy nature of cohabitation. The resilience of the creative imagination is the subtext of a moving project by Jackie Sumell. Sumell contrasts a wooden replica of the solitary confinement cell at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, which has housed Louisiana native Herman Wallace for the past 29 years, with drawings and a fly-through video of a CAD model of the home that Wallace would like to live in if he were ever to be released from captivity. The bathtub in his dream house would be the size of his current cell. At the US Mint, Sanford Biggers contributes a post-Katrina player piano that had been pierced by an uprooted tree. Damaged but not destroyed, the piano still produces a mournful rendition of the Billie Holliday classic “Strange Fruit,” about the lynching of black men. Even works that overtly have little to do with New Orleans or Katrina—such as the shimmering wall hangings of El Anatsui, or the eye-popping collages of Fred Tomaselli, or Candice Breitz’s 30-channel acapella video choir of Jamaicans singing Bob Marley’s Legend album in its entirety connect to the underlying theme of human resilience and the celebratory power of the beautiful to transform the base.

Dotted around the Lower Ninth Ward is a series of site-specific projects that provide profound encounters between visiting artists and local inhabitants. Mrs. Sarah’s House by Wangechi Mutu frames up a pitched-roof house on a corner lot where the original residence was severely damaged by the storm and then demolished by the city as a hazard. Working on a raised foundation that was the sole benefit left behind by a dishonest contractor who stole the owner’s insurance money—Mutu has built the suggestion of a future residence, which is illuminated at night by a garland of small lights. A spotlight shines upon a chair placed at the center of the “structure” waiting for the house’s future occupant to return home from her forced migration. The project will be complete when Mutu is able to replace her suggestion of a house with a real house for Mrs. Sarah.

Sanford Biggers, Blossom, 2007, player piano, steel, resin, paint, silk leaves, earth. Photo: John d’Addario. Courtesy Blue Medium.

Mark Bradford has beached an ark on another corner lot a few blocks away. Covered with a palimpsest of advertising posters, this ship—named Mithra after the Persian God of light and truth— is no more seaworthy than any of the homes that washed away in the storm. Nonetheless, it holds out the promise, no matter how feeble, that rescue is on the way. Rather than a means to escort victims away from the storm, Paul Villinski offers up the Emergency Response Studio, an off-the-grid mobile studio for artists to drive into and set up shop in disaster areas. It is crafted from one of the now iconic FEMA trailers provided as part of the pathetic and inadequate response by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The Lower Ninth Ward Village holds works by Superflex, Miguel Palma and Janine Antoni, all of which deal with the theme of repercussions. Superflex’s project, When the Levees Broke, We Bought Our House, fills a long narrow gallery with a single modestly sized black-and-white photograph of a young Danish family picnicking outside the home they were able to purchase when Danish banks dipped their mortgage rates in response to the economic slowdown anticipated by the catastrophe in the Gulf states. The photograph is for sale for $20,000, the amount the Danish couple saved on their mortgage. When the photo sells, the money will be converted into building supplies that will be distributed to local residents who are still attempting to rebuild after the storm. In the next gallery, an enormous hangar-like space is filled by Palma’s replica of a Higgins Boat. The Higgins Boat was designed and built in New Orleans to land troops on the beaches of Normandy for the D-Day invasion. Entitled Rescue Games, the ship is on an apparatus that rocks it to-and-fro as if riding the waves at sea. The flooded troop deck simulates the soothing but relentless action of waves washing ashore, delivering a mesmerizing irony— that we are more adept at landing soldiers on foreign soil than getting our civilians out of harm’s way. A final gallery houses Antoni’s Tear, which consists of a large lead wrecking ball and chain lying on the floor opposite a video projection of an extreme close-up of an eye blinking. Each blink is synchronized with the sound of the toxic wrecking ball bashing into a building, giving a new resonance to the phrase “turn a blind eye.”

Bradley McCallum and Jacqueline Tarry, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, 2007–08, oil on linen, toner on silk. Installation view at the New Orleans African American Museum as part of “Prospect.1 New Orleans.” Photo: John d’Addario. Courtesy Blue Medium.

At the McKenna Museum of African American Art, which is housed in a graceful old plantation house, the subject turns uncomfortably to racial violence—with or without Katrina. American artists McCallum and Tarry hung 103 portraits on the deep red walls of the main home. Each image is a painting of one of the silent warriors of the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott; stretched over top is a silk scrim painted with the number placards that turned each of these citizens into criminal residents of the penal system. Video installations fill the slave quarters on the property. One by Rico Gatson focuses on the moment when the racial violence at the Rolling Stones concert at Altamont brought to a close the summer of love. In the other, South African artist William Kentridge’s frame of reference is Abyssinia in WWII; his anamorphic video projection speaks volumes about the arbitrarily destructive nature of fascism.

At the New Orleans Museum of Art, the elaborately embellished Mardi Gras costumes of Victor Harris, the founder and Big Chief of the New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian group Fi Yi Yi, deliver yet another fact of urban life in New Orleans—one that doesn’t need the international art world for inspiration or validation. These works are what the mainstream art world likes to refer to as Outsider Art—but they are core expressions of the vibrant creative spirit at the heart of New Orleans, a city that may have been brought to its knees by the storm, but that— with the help of this feisty, satisfying biennial—is staking a claim to resurrection, with it’s proud, joyous plumage intact. ❚

“Prospect.1 New Orleans” ran from November 1, 2008, to January 18, 2009.

Susan Emerling is a writer living in Los Angeles.