“Projections: A major survey of projection-based works in Canada, 1964-2007”

“Projections” gathers together 19 film, video and slide projector-based art works—and one set of photographs documenting Krzysztof Wodiczko’s monumental projections—in a bid to reinforce Canada’s significant, early and ongoing contributions to this international movement. Curator Barbara Fischer highlights conceptual and self-reflexive projects; nevertheless, her choices are broad, almost consistently brilliant, and her thesis in no way heavy-handed. She doesn’t press these eclectic innovators into a single school. While the exhibition is an historical survey, and a few works seem primarily selected for their contribution to this account, the majority are engaging beyond their academic importance.

Ian Carr-Harris’s Rozenstraat 8, 1995, has two parts, one delights and the other instructs. A slowly rotating machine sends blurry rectangles of light to the opposite wall. This apparently non-objective, minimalist work is actually representational. It mimics the effect of sunlight coming through a specific set of windows and sliding across a particular wall over the period of a day. The twist on formalism is smart, but it is the mechanical, yet poetic, recognition and rendering of this quotidian event that is exhilarating. The second part, an open book describing Victor Burgin’s photo-replay of Edward Hopper’s Office at Night, is a moribund reflection on representation and reality. Perhaps it felt fresher 14 years ago.

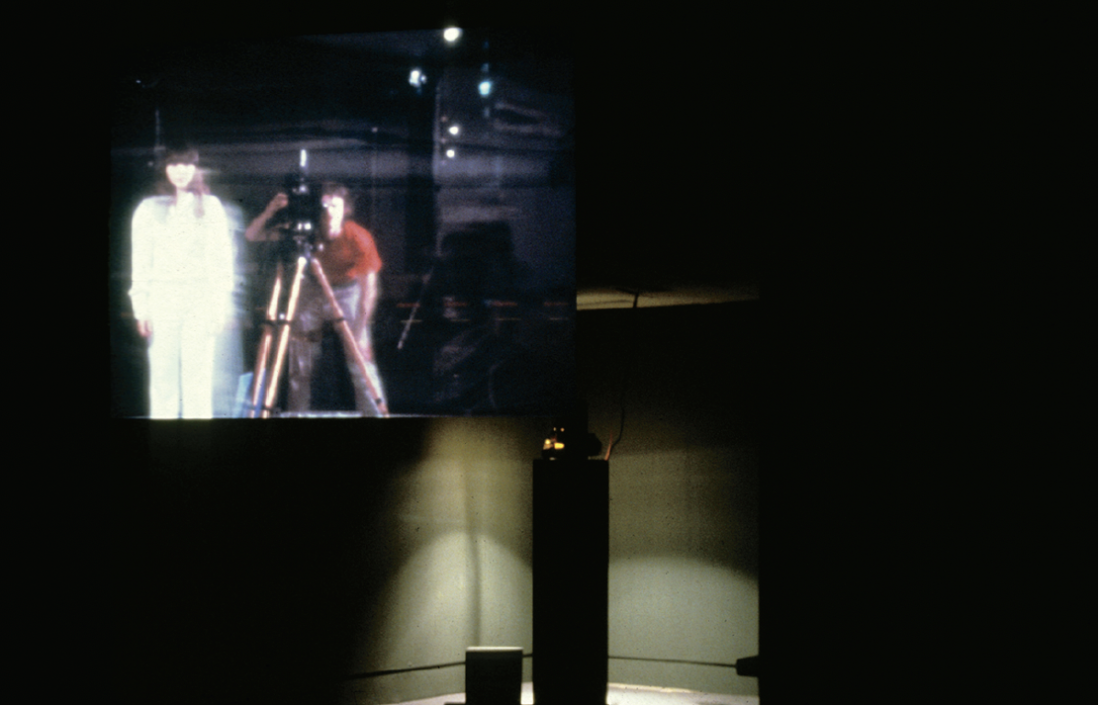

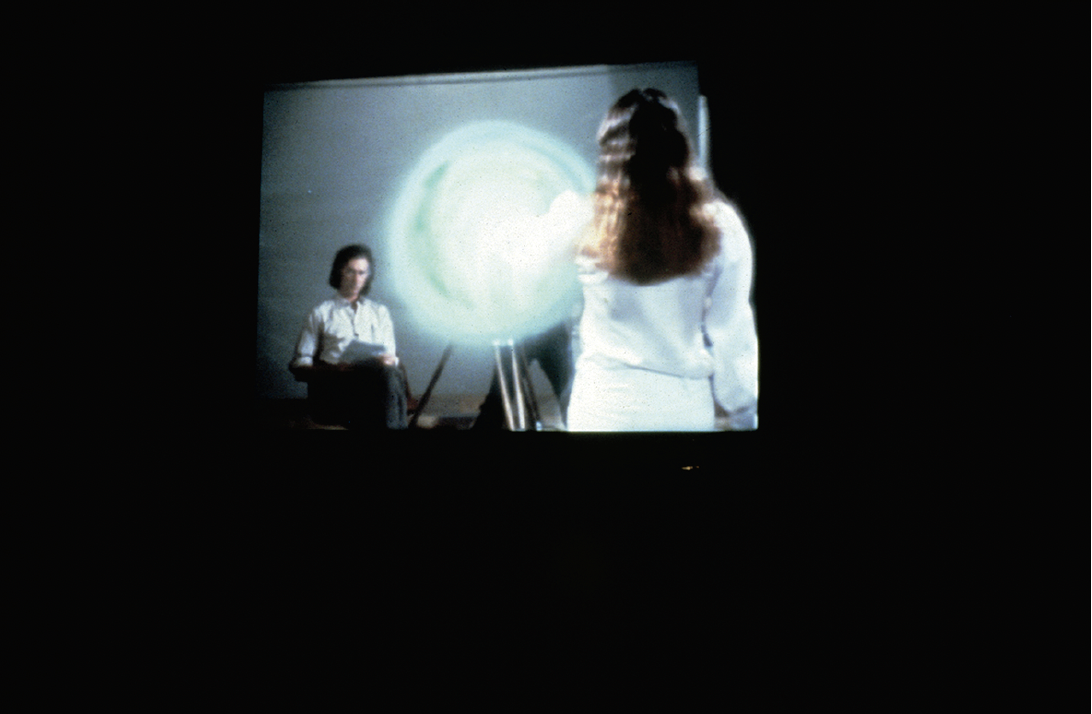

Michael Snow’s Two Sides to Every Story, 1974, is similarly of its time. The cast’s clothes are dated and actions stilted. And yet, because it performs rather than pronounces its engagement of conventions, it feels more playful, less didactic, and is a pleasure to decode. The work performs its investigations on so many levels that it rewards numerous viewings. This is an early version of the two-sided projection now often employed in recent, slicker productions by Stan Douglas and Douglas Gordon—complete with all the postmodern self-consciousness of a Jeff Wall photograph. The work bristles with Snow’s cool, intuitive inventiveness. The viewer marvels at his prescience.

Michael Snow, Two Sides to Every Story, 1974, 16mm colour film loop, 11:00 minutes, two projectors, switching device, aluminum screen, National Gallery of Ottawa. Courtesy MacKenzie Art Gallery.

Like Snow, David Askevold adds a sculptural sense of space to his pictorial tropes. As a result, his Accelerations, 1971, also maintains a currency. Projected along the wall, into the corner and over to the adjacent wall, a filmed figure repeatedly traverses a beach. His scale increases and decreases, as does his speed, relative to his relation to the camera. The distorted angle of the projection causes him to appear to accelerate as he approaches the corner then suddenly decelerate as his image hits the other wall. Like Carr-Harris’s moving window light and Snow’s doublings and displacements, Askevold’s play is elegant and humorous. A simple observation opens up complex questions about relativity, perception and projected representations.

Murray Favro’s Still Life (The Table), 1970, has a slide projection of an arrangement of everyday things (including Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media), projected onto a blank canvas that covers the actual objects. The work is a play on simulations replacing reality and the challenges of new media for painting. Looking at this and other early pieces, you get an electric sense of the pioneering moment; the artists’ inventive pleasure is palpable. Getting their hands on film’s means of production leads these artists to look under the hood and re-imagine the medium. They re-purpose the equipment and subvert cinema’s conventions and limits. As a result, most of these projects are formally playful and conceptual, more interested in self-reflexivity than storytelling. While a number of subsequent artists continue this trajectory, many also return to narrative.

When a history of Canadian contemporary art is finally written, there will be a small chapter devoted to Lethbridge. It will explain how in the late 1980s and through the ’90s that small city managed to generate brilliant exhibitions and publications (Joan Stebbins at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery), a huge collection (Jeffrey Spalding), a generous and well-managed visiting artists program (University of Lethbridge). All of this conspired to attract and sustain some of our leading projection-based installation artists, three of whom are in this exhibition.

The work of the Lethbridge School is characterized by immersive miniature installations that blur the boundary between fiction and reality. Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s Playhouse, 1997, returns the cinema to its original theatre-for-one format. David Hoffos is currently touring one of the best solo exhibitions of projection-based works of the decade. Scenes from the House Dream gathers more than two dozen complex installations to create a sprawling suburban sideshow. Bachelor’s Bluff, 2005, seconded from its tour for “Projections,” is a nocturnal beach diorama. A man paces and aimlessly throws rocks over a cliff. The waves and the protagonist appear to be “in” the set but are, in fact, ingenious reflections of video monitors on a sheet of glass between the viewer and the set. Like their precursors, Playhouse and Bachelor’s Bluff have us question our mediated perceptions, but they do so without eschewing story.

Michael Snow, Two Sides to Every Story, 1974, 16mm colour film loop, 11:00 minutes, two projectors, switching device, aluminum screen, National Gallery of Ottawa. Courtesy MacKenzie Art Gallery.

Wyn Geleynse is an early projector of animated people onto glass. An Imaginary Situation with Truthful Behaviour, 1988, features five glass houses on a long table. A naked man has scratched his way through three and is working on the fourth. Fascinating though they are, their low-tech wizardry would wear thin if not for the compelling scenarios. Hoffos and Geleynse don’t really tell stories as much as they present puzzling scenes, receptacles on which to project our own narratives.

A less inclusive, purist exhibition might have neglected videos of performances. Luckily, Fischer includes one of the most emotionally powerful documentations—Rebecca Belmore’s The Named and the Unnamed, 2002, as well as Rodney Graham’s odd Halcion Sleep, 1994. Belmore’s video captures her on the street in downtown Vancouver’s East Side as she calls out for the women missing from that location. Graham takes an unconscious ride in his pyjamas in the back of a cab.

Fischer’s other contemporary selections tend to promote the trajectory of the formalist and conceptual strains. This thesis leads to selections like Kelly Mark’s brilliant one-liner Commercial Space, 2007. A pile of monitors radiate a flickering blue glow that is actually a recording of light produced by commercials hitting a wall. But this curatorial preference also leads to the inclusion of some less interesting works: Nathalie Melikian’s clever but tedious Science Fiction, 2007, Mark Lewis’s smoothly uninteresting Children’s Games, Heygate Estate, and Robert Wiens’s spare The Rip, 1986. Greater interest in the wave of narrative-based projections that are displacing the ebbing conceptual lineage might have included works by, say, Daniel Barrow, Althea Thauberger, Michael Campbell, Rachelle Viader Knowles, and Graeme Patterson. Perhaps these artists will appear in “Projections: Second Stories.” Even so, this is a must-see exhibition, and the anticipated catalogue will be an important contribution to the history of contemporary Canadian art. ❚

“Projections: a major survey of projection-based works in Canada, 1964–2007,” curated by Barbara Fischer, was first exhibited at Justina M Barnicke Gallery, Hart House, University of Toronto from April 8 to June 17, 2007. It then travelled to the Art Gallery of Alberta, April 5 to June 8, 2008, and concluded its tour at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina from February 14 to April 26, 2009.

David Garneau is a painter, writer, curator and Associate Professor of Visual Arts at the University of Regina.