7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.

The Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. (PNIAI), Canada’s othered Group of Seven, is well on its way to claiming its centrality as a radical chapter in Canadian art. Curator Michelle LaVallee writes in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, “the PNIAI was among the first to fight to establish a forum for the voices and perspectives of Indigenous artists.” The exhibition “7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.” is a profoundly significant assertion in establishing (and re-establishing, in some cases) the brilliance of what these artists accomplished: Daphne Odjig, Norval Morrisseau, Jackson Beardy, Alex Janvier, Carl Ray, Joseph Sanchez and Eddy Cobiness. There are from 14 to 22 paintings, prints, drawings and sculptures by each of the seven artists, all drawn from the 1970s, with very pointed selections of those works which were exhibited early on as being metonymic for ethnocentric display. It’s a smartly historical tribute. It’s an opportunity to see the individual iconography, highs and lows, never-before-seen work from private collections, and relationships amongst the members.

The historical context for the group is the devastating record of racism, colonialism, and paternalism established by the Indian Act and by years of oppressive policies, practices and laws within the art history of various Modernisms. It is also the expression of the will to achieve recognition as Indigenous artists with new stories and a new visual language. All that, and a parochial art world where value on The Prairies and the Canadian Shield was established by the long shadow of the New York art world.

It is a weird and unsettling ex- perience to recall the “Primitivism” exhibition at the MoMA in 1984, with the Modernists’ reliance on so much Indigenous art, and to peer into Odjig’s So Great Was Their Love and see a Picasso face—one of her unabashed and expressed heroes—as curator Bonnie Devine showed us in the Odjig retrospective. There is a lot to learn, observe and think about in this show. Crib notes, then:

- You have to see Daphne Odjig’s work up close. Though I saw the retrospective organized by Devine, what struck me in the works shown here, where her style is offset through contrast to the work of the others, is her pulsing, rhythmic line and surface texture, thick and thin by turns. Her brushwork combines the drawn and painted line; the quickening and quivering tell the stories of empowerment. I have a deep affection for this work and its soft permeability into so much contemporary work by Indigenous female artists. Her entrepreneurial spirit, which fostered sales, organization and meetings, kept everybody fed. I wish I had known her in the 1970s. She was fearless.

Daphne Odjig, So Great Was Their Love, 1975, acrylic on canvas. Private collection. Photo courtesy the Winnipeg Art Gallery

The field is highly politicized. I want my own disclaimer. (I cut my teeth on Greenberg’s Art and Culture and was made to rehearse the same in an art history class at York University in 1978.) The opening room has a large, sticky didactic statement repeated in the catalogue: “The ongoing and intense debates about the suitability of each term mean there is no consensus on which term(s) best recognize sovereign, independent nations without imposing homogeneity, hence choice of terminology is based upon personal and political preferences as guided by our inherent right to self definition.” This didactic text about nomenclature, one repeated in the exhibition and the catalogue, tells me this for sure. Though I planned a whole children’s art education program around this exhibition and made my family come see it, took notes, wondered and raged, it’s not my story to retell without identifying my own location. The political will at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina to become, as expressed by executive director Jeremy Morgan, “a centre of excellence for Indigenous art” is certainly made manifest here.

The work has to be viewed. You need to see the extra blob of red paint on Morrisseau’s Sundance, the careful pencil line, coloured in later with ink, and the wodgy moon lines—groundless, tentative, floating moon circles in Carl Ray’s early inks, such as South Wind. You need to see these up close. The work has been beautifully conserved, although not all the work is travelling. Janvier, Odjig, Beardy, Morrisseau and Ray all developed a new language of visual form, and a few were and are geniuses. The exhibition’s organizational flow allows for small walls devoted to individual artists, as well as thematic groupings that tackle personal narratives, ceremonial content and other significant ideas that allow for multi-artist groupings on the walls. The lighting at the WAG is not up to snuff. The glare on Sanchez’s print work is annoying. I start to yearn for a more explosive paint colour on the walls—one to match the revolutionary content.

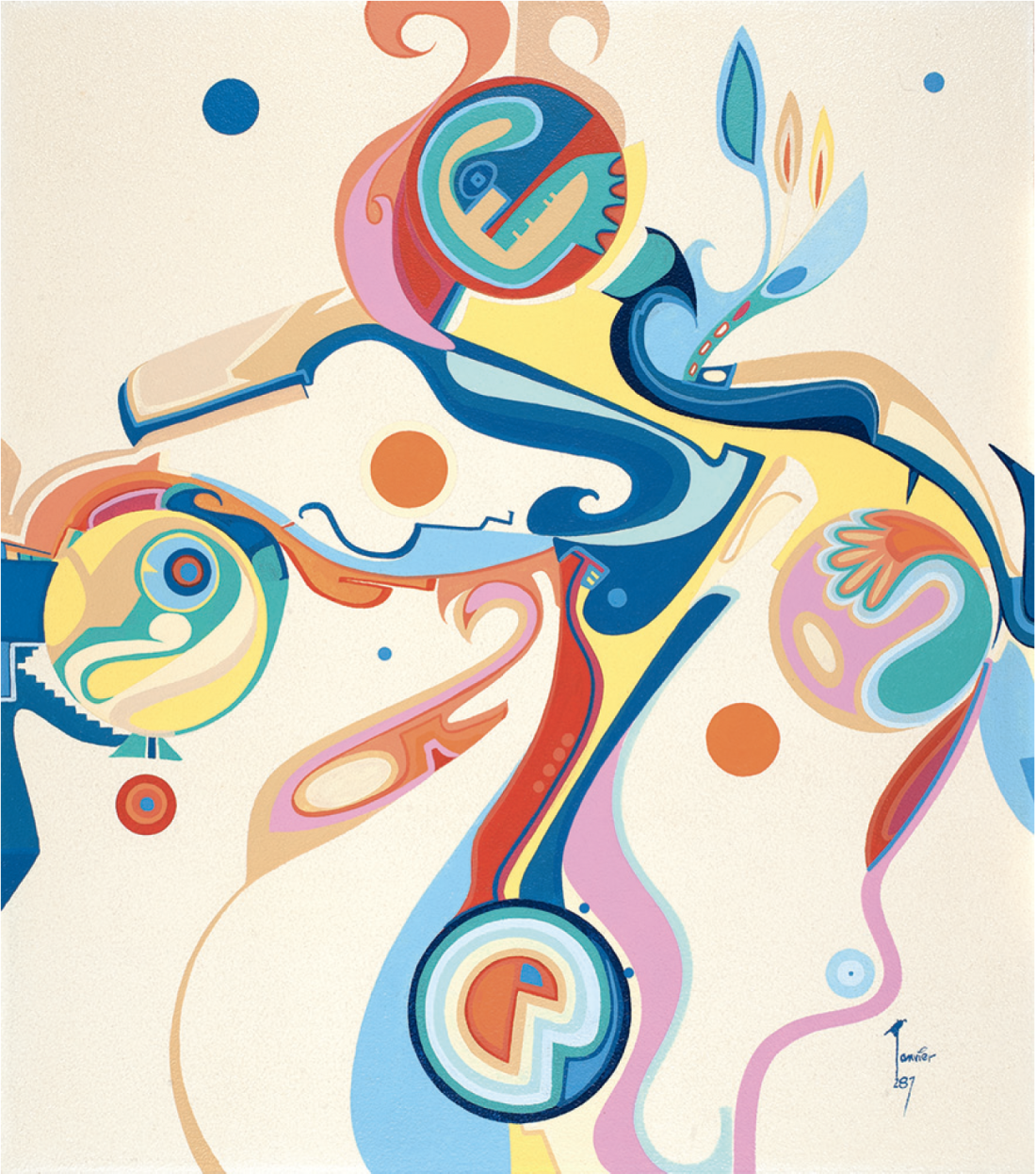

Janvier turns out to be the biggest surprise. I thought I knew the work. Here is a chance to see more and make a judgment. The play and invention, that business with scale, the insect, bird and bead imagery, that and the open, optimistic format. New colours. Janvier’s language is as original and as iconic as Morrisseau’s and as Odjig’s. He is inimitable, brilliant, connected, beautiful. I wish I had seen the Alberta retrospective.

Joseph Sanchez. Here are apocalyptic visions, conflation of soft porn, Daliesque turns, psychotropic remnants of the ’70s and so much more. I am only mildly offended by the nudes this time round, as his first-person narrative about specific works, events and influences have made his intentions so much clearer. His hybridity and use of historic models express the conflicts inherent in his visual vocabulary, psyche and politics. The darkest moment in the show is the pairing of Sanchez’s ghost dancer in La Fenixera with his biblical vision of St John’s whore of Babylon. The ghost dance is not as widely known as it should be, neither in its initial historical moment as resistance, mourning and Christian influence, nor in Sanchez’s very moving imagery, where the use of black and white, positive and negative and borderline grotesqueries show some resemblance to Georges Rouault’s tragic work. Here is the act of reclamation and resistance. A whole new explosive and radical syntax.

Alex Janvier, The Four Seasons of ’76 (detail), 1977, acrylic on Masonite. Courtesy of Janvier Gallery.

Jackson Beardy’s originals are writ large—so many of these in print reproductions around Winnipeg. The work is brilliant to see in the original. Printmaking allowed for the necessary financial support, and many prints were based on original paintings.

It is evident there is no need for stylistic conformity. Bound by a common purpose, the group of seven artists were pluralists. Cobiness played at times with a cross-hatched illustrative and realistic portrait style, heightened by symbolism. The explosive brilliance of this group is that it held through all the political, stylistic and financial tension. Curator LaVallee wisely acknowledges the challenges of reconstructing a singular historical record and has opted for multiple forms and approaches to scaffold insightful commentary: Voices, writings, art criticism and interviews of artists and art historians establish the messy and contradictory beginnings during the 1970s. Even the now-rarely seen grid, once a staple of art historical texts, resonates anew in this version as social activism and Indigenous politics and the activities of the PNIAI explode the x and y axes. Like many of the art catalogues and texts produced during the 1970s, this catalogue has this same delightful heterogeneity, an antidoxa that combines voices, stories, photographs and understandings for a lot of ambitious art making. Essays by Barry Ace and Lee-Ann Martin, and the reprint of Tom Hill’s work of 1974, are especially illuminating for the specificity of historical research, while the primacy of quotes by the artists, some deceased, others contemporary, make this a valuable source text.

What this rich exhibition and catalogue demonstrate is that the work by the seven, and its conceptualization in the 1970s, redefined the rules of the game. The language provided by Morrisseau spawned into the intractable Woodland School. The stories that found form through Beardy resulted in Selkirk Avenue murals that continue to influence artists two generations later. Odjig’s persistence and sheer will as an organizing genius was crucial, her imagery generative for other female artists. This is an exhibition worth seeing across the country and one to return to many times. The catalogue as an accompaniment stands on its own as a worthwhile text for any art library purporting to know something about art made in Canada in the 20th century. A lot of groundwork has brought this vision forward—all respectfully noted by LaVallee through her inclusive methods throughout the texts—fertile ground indeed for development by subsequent artists, curators, storytellers, researchers and art historians. ❚

“7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc.” is on exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery from May 10 to September 1, 2014.

Amy Karlinsky is a Winnipeg writer and educator. She saw this show with 150 students from the Winnipeg School Division.