Positioning Subjects

Desire and Distance in the Art of Andrea Fraser

The interview you are about to read (although “encounter” might be a better word) was recorded less than a month before the opening of Andrea Fraser’s exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York. It was her first commercial exhibition in New York in 13 years, and, for Fraser, the gallery was an apposite choice. She told me that Marian Goodman had been “the guardian of conceptual traditions and many of the artists and art practices that I looked to since I was a young artist.” In a way, the exhibition was a homecoming.

A smartly chosen sample of work done over the last 32 years, the exhibition included the range of her mediums—photography, sculpture, text-based work, video and performance—as well as the ideas to which those mediums were in service. “My work swings between extremes of pseudo-social science, sociological, economic and political research, on the one hand,” she explains, “and often highly exposing psychological investigations of desire and emotional investments and conflicts, on the other.” Her conversation describing the ways interaction works within and across her practice constitutes an autobiography of ideas. What is especially appealing about this process is her recognition of the role her own subjectivity plays inside that construction. What her intense self-reflexivity revealed is a capacity for empathy, a word much underappreciated in the intellectual hothouse that has been her arena since 1982 when she entered the School of Visual Arts at the age of 17.

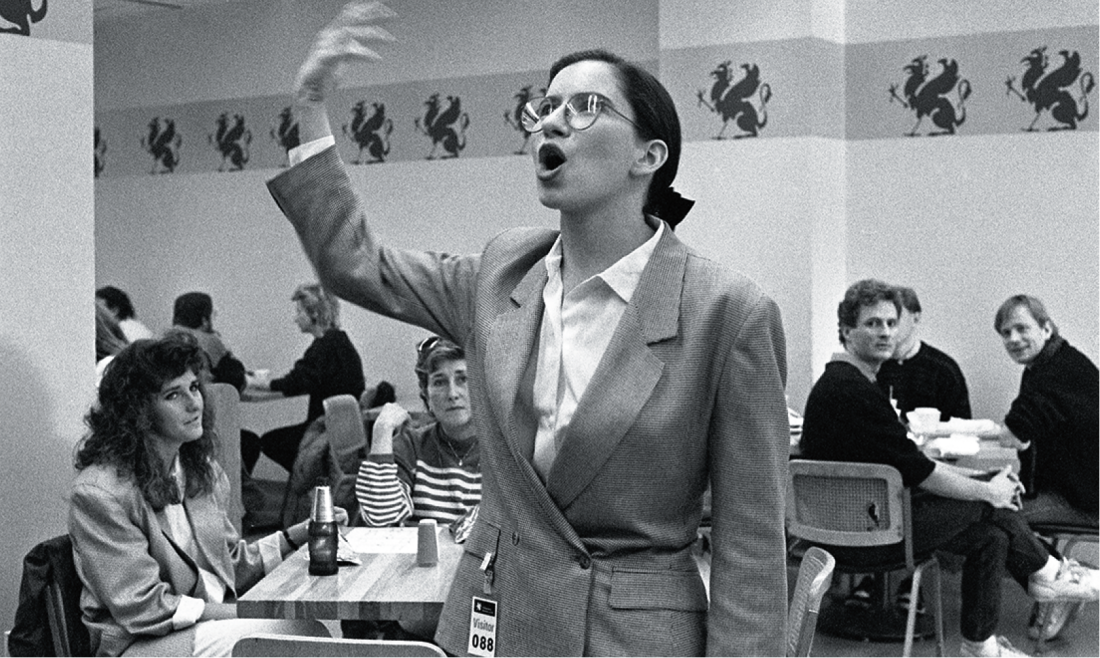

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk, 1989, performance. Performance documentation Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1989. Photo: Kelly & Massa Photography. All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

In talking about her early influences in the Whitney Independent Study Program, 1984–85, Fraser refers to the indelible impression made by Yvonne Rainer’s 1971 film, Journeys from Berlin. What she appreciates is how Rainer was able to brilliantly bring together the political and the personal narratives central to the film’s structure. In her own work across a variety of disciplines, Fraser herself has shown much of that same syncretic inclination and brilliance.

The other notable aspect of her practice is the consistency with which these ideas find forms of communication in language and in performance. She began this careful consideration in her museum performance pieces, and that attentiveness has persisted. In Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk, 1989, Jane Castleton, the docent, was less a character than a subject formation, whereas the tour guide in Welcome to the Wadsworth, 1991, shifts from a benign provider of personal information to a frantic spokesperson espousing “a kind of White supremacist, Yankee, ethno-nationalism.” It is both an amusing and frightening transformation.

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk, 1989, performance. Performance documentation Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1989. Photo: Kelly & Massa Photography. All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

Transformation evolves to transference. In This meeting is being recorded, 2021, Fraser plays seven women, including herself. The set of accompanying director’s notes, 15 texts with different headings (“Race versus gender,” “Hatred, longing and agency” and the longest document, “Taking back racialized projections”), also includes acting suggestions, camera shots and timing cues; it is a detailed working document that indicates how the piece could be realized. Digested from transcripts of six 90-minute-long discussions recorded in 2020, the women apply a psychoanalytic group relations methodology to examine issues around their own unrecognized racial prejudices.

If the text is impressive, Fraser’s ability to shift from one character to another raises the bar even higher. Her 99-minute-long performance (which she recorded in a single unedited shot) is a tour de force during which she embodies a range of subtly different subjectivities. When asked to be a television reporter for TV Cultura during the 1998 Bienal de São Paulo, she finds the ideal tone and manner for her persona. Reporting from São Paulo, I’m from the United States, 1998, was recorded but never broadcast. Fraser re-edited the footage and turned it into a video installation that presented a socio-economic analysis of the biennial’s theme, which was art and anthropophagia (put another way, cultural cannibalism). The funniest moment in the coverage comes when she interviews herself. Asked by her reporter-self if she is enjoying the biennial, her artist-self says, “I feel justified in being who I am,” which perky assurance draws from her reporter-self the admiring observation, “That’s great, I envy you.”

Andrea Fraser, Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk, 1989, performance. Performance documentation Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1989. Photo: Kelly & Massa Photography. All images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

This self interview is itself a call for envy, a commentary that turns speaking into an anthropophagic act, the interchangeable journalist and artist consuming their own selves and their adopted identities. Fraser is picking up and consuming the biennial theme “that cannibalism is not a diet but a metaphor”; and the inhabitation is characteristic of how she deploys her inventive sense of serious humour.

It is easy to overlook how layered these pieces are because Fraser is such a skilled writer and performer. She has an unerring ability to find the enacted person who best articulates the way institutions and their procedures function in our lives. Psychologically, she is an ensemble cast of one. It’s like watching the unconscious become flesh, and, in that way, her work takes on the nature of something that could be called a new testimony.

Andrea Fraser’s exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York opened on January 12 and continued to February 25, 2023.

The following interview was done by phone to Los Angeles on Thursday, December 15, 2022.

Men on the Line: Men Committed to Feminism, KPFK 1972, 2012, performance. Performance documentation Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2012. Photo © The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu.

BORDER CROSSINGS: I’ve cobbled together your description from a collection of early interviews and this is who emerges: a half-Puerto Rican school dropout raised by a pair of downwardly mobile hippie parents who felt threatened in your community because your family was different, and who was obsessed with equity because you were a runt.

ANDREA FRASER: You didn’t include lesbian feminist household in there. There were different phases of my childhood. My first two years were in Billings, Montana, and then Berkeley in 1967. I was on my parents’ shoulders at the famous People’s Park protest. Then from Berkeley we moved to San Mateo, which was at that time a very conservative suburb of the Bay Area where the neighbours were threatening to put a bomb under our house or burn it down. One of our pets was shot and killed. The police were often coming around. It was scary. Then my parents divorced, my mother came out as a lesbian and we moved back to Berkeley into a much smaller all-female lesbian feminist household. And that was a very different environment again. I went from an all-White suburban school to a Black majority school, where I had the experience suddenly of being White. It was a complicated childhood. I dropped out of high school a month before my 16th birthday and moved to New York a month after my 16th birthday and started art school two months after that.

You were memorizing Adrienne Rich poems and you bused to San Francisco when you were 13 to see Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974–79). But when you went to New York, you regarded yourself as uneducated?

Yes. I struggled with a sense of educational failure and deficit. I was the youngest of five kids and precocity was more or less forced on me. I think I was already a bit of an autodidact by the time I moved to New York and had a sense that I was going to have to find my own way and educate myself. When I got to New York, I dove into going to museums practically every day of the week, mostly the Metropolitan. I was just looking and looking. Even though my mother had been a painter and I was exposed to art books and art magazines, I really hadn’t gone to museums very much growing up.

Men on the Line: Men Committed to Feminism, KPFK 1972, 2012, performance. Performance documentation Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2012. Photo © The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Yi-Chun Wu.

A good friend of yours, Allan McCollum, told me that his autodidactic strategy was to read the footnotes at the end of the articles in Artforum and then read all the books that had been mentioned. I gather the Met was your autodidactic strategy?

Yes. I don’t think I was reading that much. I met Allan when I was 18 and I was his studio assistant for a while. We became friends and his autodidacticism inspired me. He was reading things that other people weren’t reading. For example, he talked to me about Winnicott and Melanie Klein at a time when nobody was reading them. Everybody was reading Lacan and that was it. We did connect over being autodidacts and being a little bit outside the channels through which artists usually enter the art world. His parents were factory workers while mine were artists and intellectuals, so he was much more of an outsider than I was. But I had started reading art criticism and critical theory by the time I was 17.

You ended up at the School of Visual Arts and then you went into the Whitney Independent Study Program. Everything I’ve read indicates that that was an extraordinary time for you.

I had amazing teachers at SVA. I took performance with Simone Forti and video with Dara Birnbaum and painting with May Stevens, who brought Adrienne Rich in to speak, and drawing with Tom Lawson. Tom passed out a bibliography that included articles from the journal October and I went over to him and said, “What’s this? It says when it was published but not where.” He said, “That’s the name of the journal.” I became Tom’s assistant and he introduced me to Allan McCollum, who introduced me to Louise Lawler. And so it went. I started to learn through them about developments in the art world of the ’70s, the early ’80s and the Pictures Generation, in which Tom was very involved. But it was my class with Craig Owens that really changed my life and put me on the path to the Whitney program. In the first class, he did a reflexive Foucauldian critique of the situation of the classroom that immediately resonated with my anti-authoritarian, feminist childhood. He was an absolutely compelling, brilliant person. That was the class where I connected with Gregg Bordowitz, Tom Burr, Mark Dion, Collier Schorr. It was an amazing group. All of a sudden, I was in contact with people who were much further along artistically and intellectually than I was, and at least a couple of years older. That really pushed me forward. It was only a couple of months after I got into that class that I applied to the Whitney program. Somehow, I convinced the head of the program that I knew enough to fit the mould, but I was also incredibly anxious. I had classic imposter anxiety all the time.

Official Welcome, 2001, performance. Performance documentation, Morse Institute of Contemporary Art, New York, 2001. Photo: Sarah Kunstler.

You’ve also said that Yvonne Rainer’s Journeys from Berlin (1971) was particularly important. Was it the beginning of your awareness that you could generatively combine the personal, the political and the social? In the film, she includes a journal she wrote when she was 17, the repressive politics of Germany during the Baader-Meinhof period, and there’s a fictionalized therapy session. That sounds like fertile territory for you.

Yes. I saw Journeys from Berlin when I was 18. I was in the Whitney program for a year and a half and Yvonne was on sabbatical making The Man Who Envied Women (1985) the first year I was there, so I didn’t have contact with her until she came back. But Journeys from Berlin was hugely important. I can highlight three things that are still very much with me. One is the way she brings together the personal and the political in different discourses and narratives. She combines the historical narrative of Alexander Berkman’s attempt to assassinate Frick, the political discourse around Baader-Meinhof, her teenage diaries and then the analytic session. Those were the four primary discourses in the film, and how she weaves them together also was incredibly important for me. She didn’t do it through a traditional narrative, but she spatialized them within a time-based medium. She choreographed them in a way that somehow created a spatial sense of structure within the time-based medium of film. That was hugely important when I started to think about how to construct my own scripts, and particularly when I started to develop multi-voice performances with the ambition of performing in social fields. The third thing that was so important was the psychotherapy sessions you mention. In the foreground there’s a patient and the therapist at a desk, and then in the background of the deep black sound stage, there are different things unfolding, which is a brilliant representation of the unconscious. But the most brilliant thing is how she represents transference: within a shot/counter-shot structure, the analyst keeps changing from a man to a woman to a boy. But the very most brilliant thing is how these psychological structures are not only represented but woven into the structure of spectatorship, as the viewer projects into the deep space of the image and gets sutured into the relation in the shot/counter-shot. I haven’t seen the film for a long time, but I remember it very, very acutely. The part of the film that never registered for me until much later is that it’s about terrorism and suicide and it related to her own suicide attempt while she was in Berlin. That I repressed or blocked that out for years is so strange.

In 1984 you made an artist book called Woman 1/Madonna and Child that combines a couple of things that have continued to hold your interest. One comes out of your looking in museums, so you superimpose paintings by Raphael and de Kooning, and the other employs the idea of appropriation. That mechanism became especially important for you because it lifts texts and words from other sources, mixes them up and repurposes them. Were you consciously developing a methodology?

Absolutely. That was the first work I did when I stopped painting and drawing. I had been working with strategies of appropriation, quotation, montage and superimposition in those mediums. They were very prevalent at that moment. I was looking at David Salle and Sigmar Polke. Then I started looking at artists who were carrying over those strategies to other mediums, like Barbara Kruger, who was working with image and text. With that artist book, I went from appropriating images and texts to appropriating museological forms and formats, in that case the exhibition brochure, and later also wall texts and posters. But I was creating my own versions of them. From there I went to the idea of appropriating positions and functions with an institutional context through performance. That first move to appropriating museological formats was very influenced by the work of Hans Haacke, and my shift to appropriating positions and functions really developed out of an engagement with Louise Lawler’s work, which I wrote about in 1985. I was thinking about how she had taken up the position of a curator or an art dealer or a publicist in various works in the early ’80s, not in the medium of live performance but in the medium of conceptual intervention. That, combined with my high school foray into theatre and my engagement with film and film theory, led to my early museum tour performances. So I do think it was a methodology. One was the methodology of appropriation and the other was the methodology of site-specific intervention, which was also deeply influenced by Daniel Buren and Michael Asher. And that developed into what I think of as my most basic methodology, which is reflexive critique or analysis.

Untitled (video still), 2003, project and video installation.

Your intention with your artist’s book was to infiltrate the museum bookstore. There was a subversive intent, a resistance to the structures of the art museum, built into your thinking from the beginning.

I think that was connected to growing up in a counterculture hippie family. My earliest memories were being in my mother’s garage art studio and going to anti-war demonstrations. I marched with my mother in the Gay Pride parade in San Francisco in the ’70s. I gravitated toward art in part because I saw art and artists as agents of change. There was also a connection between avant-garde traditions in art and the counterculture ethos in which I grew up. It’s a complex calculus because there was something very compelling about the mythos of the artist genius. But in my mind, it was also the mythos of the artist as a revolutionary, a radical agent of change. How to be that kind of avant-garde agent of change was very consciously the problem that I set myself. At the same time, the failure of those avant-garde ambitions was much discussed in the ’80s. I remember it was the decade of the end of everything: the end of painting, the end of the avant-garde, the end of modernism. In some ways it was a decade in which the art world—in the very specific context of the art world in New York—was grappling with the failed narratives and ideologies of colonial, patriarchal and, to some extent, White supremacist politics imbedded in the modernist canon.

It was all about endings. It was the death of the novel, too. Everything was an eschatology.

What was going on? We still had 15 or 20 years to go before the end of the millennium.

Was writing the piece on Louise Lawler the moment when you recognized what it is you wanted to do and how you were going to do it?

It started a year before that with Woman 1/Madonna and Child. I was already looking at the work and writings of Haacke, Asher and Buren; I was in Benjamin Buchloh’s class; and I was reading Douglas Crimp on the museum’s ruins. I was collecting all the books that were published by the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design Press. I often say that while institutional critique might not have developed in Canada, it was framed and articulated in Canada through the publications of NSCAD and Art Metropole. Books like Museums by Artists and Performance by Artists were really important to me, as were the books of Asher, Haacke and Buren that were published by NSCAD. What Louise’s work added for me was thinking in terms of performance. Not performance as live art but the performance of functions within an institutional context, and working at the margins the way she did in the early ’80s. It was about finding these points of intervention that were not in the centre in the gallery space but that were on the periphery. It was what I tried to theorize in terms of the supplement. It was a couple of years later when I was writing about Allan McCollum’s work that I “discovered” Pierre Bourdieu’s work, which nobody in the New York art world was reading at the time. The only place where I came across a reference to him was in an essay by Martha Rosler. His methodology of reflexive sociology and his analysis of the social field, especially the fields of art and power, and of the aesthetic disposition and its role in the formation and manifestation of class hierarchies and forms of social domination, all became my central framework for the next decade, and still are.

Reporting from São Paulo, I’m from the United States, 1998, 5-channel SD video installation, colour, sound, 5 minutes 40 seconds, 4 minutes 6 seconds, 2 minutes 25 seconds, 5 minutes 16 seconds, 6 minutes 50 seconds. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser.

There were artists, I’m thinking of Fred Wilson and Mark Dion, who were using museum collections to advance their particular take on institutional critique. You do something quite different because you bring your own body into the dialogue. That strikes me as a fundamental shift. In looking at what other people were doing, did you have to find a space that hadn’t already been occupied?

When I started doing the museum tours in 1986, I don’t think I was aware of any other artists of my generation who were picking up those threads. The space that I was trying to find, or create, had a lot to do with feminism. I was trying to work at the intersection between the political practices coming out of conceptual art that were often researchbased and very site-specific and feminist practices that were investigating subjectivity and subject formation, often in the mediums of performance and moving image. What was developing as a theory of institutional critique was largely influenced by the Frankfurt School and Foucault. I also wanted to bring in feminist theory, especially psychoanalytic feminist theory, and feminist critiques of the art field, the museum and of academia. I did grow up in a lesbian-feminist household. The reason why feminists gravitated toward performance was because of the presence and the centrality of the body for feminist politics. The body is really the crux and the crucible of gender-based violence and gender-based domination. However, in my early performances, I was thinking less about the body than I was about subjectivity, about desire and about subject formation within particular institutional fields. I was thinking about embodied discourse and about how to engage language in a gallery space without putting text on the wall. It wasn’t until much later in the ’90s that I started to think more explicitly about the body.

I can see that Hans Haacke and Michael Asher would have been influences, but in the late ’60s and mid-’70s artists like Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke were using their bodies in much more instrumental ways. There was certainly no theory or discourse attached to Fuses (1967) or the Starification Object Series (1974). But I did notice one moment in Official Welcome (2001) where you describe yourself not as a person but as an object in an artwork. That declaration is one that Hannah Wilke made in the photo performance called I Object, Memoirs of a Sugar Giver (1977). She uses the word “object” as both a noun and a verb; she’s an object and she objects to being one. I find that complicated sense of agency in your work. Did the performances of Schneemann or Wilke have any influence on you at all?

Reporting from São Paulo, I’m from the United States (video still), 1998. © Andrea Fraser.

Not so much. Part of that is because the New York feminism I landed in was a vigorously anti-essentialist psychoanalytic materialist feminism. There was a split from, and rejection of, a lot of feminist practice from the ’70s at that time, which included artists like Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke. The feminist artists I was looking at were Yvonne Rainer, Mary Kelly, Barbara Kruger and Martha Rosler. I had grown up with Judy Chicago and I did cut class to go to the opening of The Dinner Party when I was 13. I spent hours sitting around with my mother and her friends, going through the book and talking about all those women who were represented at the table. When I got to New York, that was an embarrassment to the people I was studying with. It took me a while to figure out what was going on with that. On the one hand, I was trying to bring together feminist theory and practice with what was starting to be identified as institutional critique, which in Benjamin Buchloh’s writing was completely identified with male artists. But there was also a split within my sense of feminist theory between materialist and conceptual practices and the psychoanalytic perspective that I had become invested in and the feminism of my childhood, which these perspectives rejected as essentialist cultural feminism. I think that influenced how I took up performance much more through language than the body. The investigation there was about subject production and how subjects were produced in institutional contexts to serve particular functions. In those early performances it was specifically the subject position of a female volunteer of a certain class. I stopped doing performances for a good part of the ’90s and it wasn’t until Official Welcome (2001), Little Frank and His Carp (2001) and also Art Must Hang (2001) that I started to think more about my body in performance.

You mentioned language and about how important writing is to you. In one of your performances, the observation is made that although Fraser’s talk “may seem casual, even aimless at times, it’s based on a carefully crafted script.” Am I to take that admission and self-reflection as accurate and intentional? There is much evidence of the craft of writing in your work.

It’s funny because when I started out as a painter, I was really quite a draughtswoman and very invested in that craft. Then I stopped making objects, but my energy around craft shifted to language and writing and performance. In addition to the conceptual aspects of my work and the theorization of practice and of method, I think I still value craft, basically in the form of rigour. It’s gratifying to hear from you that it’s evident in the work. I continue to think of writing as one of my mediums. Besides my scripts, most of the texts I write are destined for publication on the page and are not works of creative writing in any traditional sense—I suppose they could be called non-fiction creative writing even if most are heavily researched attempts at social and political analysis. But I still think of them in the same way that I think about creating a performance script or any other artwork. I’m thinking about them site-specifically, about where they’re going, what the audience is, who the readership is likely to be, how they’re going to exist on the page, what the voice is. Probably the most challenging thing for me, when I’m writing anything, is figuring out what that voice will be. Sometimes I describe myself as basically a rhetorician in the way I work. I’m always trying to make an argument. Even when it’s not a polemic, I’m very focused on how it will impact the reader and the viewer. These days I mostly think and talk about that in terms of what it will activate as an emotional response, a thought process, or a physical response.

Um Monumento às Fantasias Descartadas (A Monument to Discarded Fantasies), 2003, mixed media (Brazilian carnival costumes), dimensions variable. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser.

Another dimension of your writing and performance is that you want the viewer to be involved. You want the spectator to play the role of a spectator, which strikes me as a slightly Brechtian way of coming at things.

Brecht has definitely been a huge influence, but at this point I’m thinking of my work less in terms of critique than in terms of an analysis that is modelled on psychoanalysis. But the point is not that I’m engaged in some critical or analytical process or practice. That’s part of my research. What’s crucial is that the work itself activates a critical and analytic process for the viewer. It’s what the work does. It’s not what the work is. If I’m working self-reflexively, part of my intention is to activate a kind of reflexive process for the viewer, not to present myself as an exemplary practitioner of a certain methodology to be observed by a spectator who’s not touched or involved. I mean, that’s a godawful position to be in. Unfortunately, it is one where I sometimes find myself because my work often activates responses that psychoanalytically I understand as very defensive. Being successful at touching and engaging people in a reflection on where they are and in what they’re doing in the moment, which is my grail as an artist, can also include activating feelings of shame and anxiety and discomfort. One of the ways of responding to those feelings when they get activated is to push them out and attribute them all to the object that activates them. And that does happen. But that’s part of the risk I take. Of course, all those things that activate discomfort are also mine, and I’m putting them out there not just to own them, but, I hope, to engage the viewer or the audience in a kind of mutual ownership. Going back to craft, Freud describes aesthetic pleasure as a kind of bribe that allows for the evasion of repression and defences. So in a way, I’m bribing the viewer with my craft to join me in feeling and thinking about painful things.

Do you think about a narrative arc in the writing and the performances? I like the way Jane Castleton develops as a character. She starts out combining the aspect of a schoolmarm and then becomes slightly condescending and pompous. But as the gallery talk continues, she begins to unravel, and the language does the same thing. How carefully did you plot the way that her character reveals itself as she does her gallery talk?

I do think about narrative arcs, although I don’t think I would have admitted that in the ’80s and ’90s. I also was resistant to calling Jane Castleton a character. I thought of her as marking a position defined by a function and a discourse. I was thinking of narrative not in terms of the development of a character but in terms of the formation of a subject. It was more about a subject position within a specific institutional context and a relationship to its discourse and how these intersect with social structures and social dynamics and histories. That’s how I was conceptualizing Museum Highlights: A Gallery Talk (1989). The arc of Museum Highlights is towards this increasingly extreme identification with the museum and its objects. The crux of that is when I say, “Wouldn’t it be nice to live like an art object, a sophisticated composition of austere dignity, vitality and media quality?” I’m quoting descriptions of art objects from museum publications. By the time I get to the end, I’m applying those descriptions reflexively to myself and taking on the ideals and the aspirations that are contained in those descriptions of artworks. It’s the final collapse of the person in the object. In Welcome to the Wadsworth: A Museum Tour (1991), I start as myself rather than as a “character,” and then I increasingly identify myself into the position I think the museum creates for its public, in that case a kind of White supremacist, Yankee, ethno-nationalism.

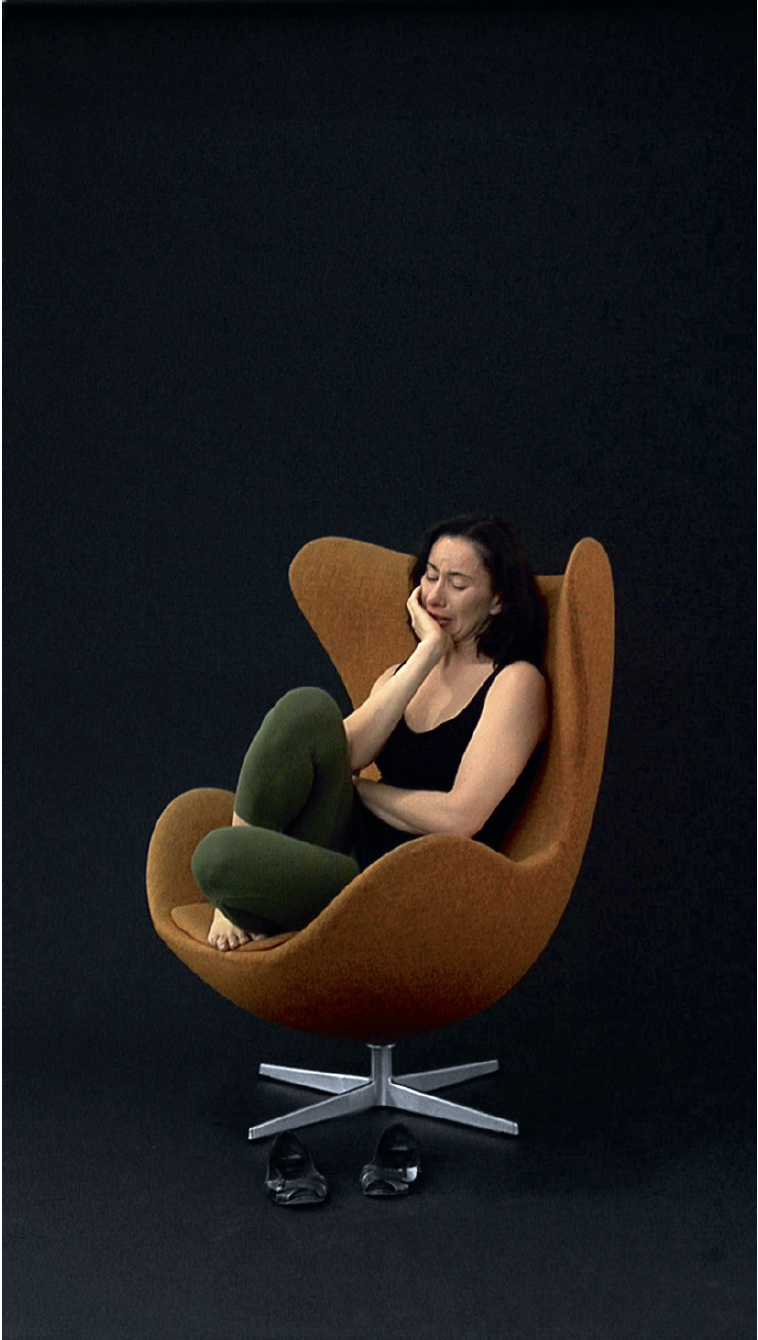

Projection (video still), 2008, 2-channel HD video installation.

You are so careful that you choose a Jacobsen egg chair in Projection (2008). And when you have that picture taken from the New York Times Style magazine, you’re sitting on a Herman Miller office chair and behind you more of them are piled up. It looks like all the choices being made are very conscious.

Yes, the poetry of chairs. For Projection I just knew it had to be the Arne Jacobsen chair. It was only later I connected that to the fact that the analyst I had been seeing in New York before I made that piece is named Jacobson. His name is spelled and pronounced differently, but essentially the same name. So not entirely conscious! But that is not the psychiatrist I perform in the piece itself. That was someone else. Actually, that chair cost more than the sessions with the psychiatrist. I was lucky to even find it. At the opposite end of the spectrum is the chair I use for Men on the Line (2012/2014) and This meeting is being recorded (2021). The story there is I was performing Men on the Line at MoMA and I needed a chair with arms. They kept offering me these expensive, overdesigned armchairs. Then right outside the theatre, I noticed a cheap office side chair. It was the chair the guard sat in. And that’s the chair I used.

Do you rehearse the performances? I notice small details: when you pick up your dress and move it on the podium, when you touch your nose nervously, or the slight accent in Museum Highlights, or that small hiccup when you say, “I’m honoured to be honoured here this evening.” All of those seem like carefully orchestrated moments. Am I reading too much into them?

They are rehearsed. I rehearse them into the ground and choreograph them in minute detail. When I developed my first performance in 1986, for the New Museum, I didn’t intend to perform myself. I had auditioned and cast an actress, but I was so late in finishing the script that she didn’t have time to memorize it for the first performance. Then I realized that I had memorized it in the process of writing. I also realized that the writing wasn’t just a process of putting words on a page, but it was hearing the voice, the accent and the inflections. That continued to be the case with all my performances up to Art Must Hang, when I started working from audio and video recordings. But with the earlier works, I was directing them as I wrote them. I was writing scores, if you will, and not just scripts. May I Help You? was originally performed by actors in 1991. I auditioned a number of people, and then I cast three performers, who would be in the gallery 10:00 to 6:00, five days a week, for the duration of the show. They were frustrated because I was giving them “line reads.” I would say, “No, this is not about you making an interpretation. This is how this line is supposed to be delivered.” They did it to varying degrees. It’s actually very hard for me to rewrite things because I revert to the earlier version. My more recent pieces, including This meeting is being recorded, Men on the Line and Projection, and also Not just a few of us (2014), are different because, like Art Must Hang, they’re based on found or generated video recordings. The accents and the inflections are mostly following the recordings very closely, while the postures and gestures and choreography are largely invented, and minutely choreographed, especially the most recent one.

Projection (video still), 2008, 2-channel HD video installation.

It’s interesting that you say “choreographed” because the same care is evident in the technical and spatial moves you make in your pieces. In Philadelphia your run-through of the copious list of attendant cultural institutions apart from the museum itself is an impressive piece of acting and movement. Then in the Bilbao piece you’re using five hidden cameras, so the construction becomes a significant editing process. You’re selecting shots from five different cameras to make the narrative what you want. In it, the gallery visitor you play goes from naïve wonderment to that sexy grind on the curvilinear walls of the museum’s interior. She goes through some transformation as she’s seduced by the voice of the audioguide.

I’ve done only two pieces where editing was really an important factor. Museum Highlights was the first piece for which I had a shooting script and I worked out all the shots and how they would be edited in advance. There wasn’t a picture storyboard, but the shooting script broke it down page by page, shot by shot. The other example is the piece I did for the Bienal de São Paulo in 1998 called Reporting from São Paulo, I’m from the United States. That was shot by a television crew for a station called TV Cultura. It was supposed to be broadcast nationally, but that never happened. That piece did have a shooting script, but a lot of construction was done after the fact in the editing process. Most of my work is conceptualized as performance. Projection is two-channel and is constructed as a series of one-sided dialogues, so those were shot one by one. Men on the Line and This meeting is being recorded, which at 99 minutes is a feature-length film, were both recorded in one shot. Men on the Line is about 45 minutes. They were rehearsed and performed to be recorded in one shot and they’re essentially unedited. That was important to me. I’m particularly interested in how This meeting is being recorded exists between theatre and film and performance. There’s something very specific that a video installation can do, and a projected performance can do, that can’t happen in a live performance. It’s not theatre or theatre on film and it’s not cinema. I think it is its own genre in a way.

Little Frank and His Carp (video still), 2001, SD video.

Museum Highlights exists in three versions, doesn’t it? You did six performances to a live audience of 20 or 30 people each time. Then there’s the video and finally the text that was published in October. Do the works mean differently when they take on different forms?

I think of them as three versions of the same project. The live performance was conceptualized to be performed to a group of people who moved through the museum. The video is not a video of a live performance. I went back and shot the video without an audience. I wanted the viewer of the video to be the primary audience of the video, not a secondary audience with a voyeuristic relationship to a primary audience, which is often the case with live performance documentation. Also, it had a different model. The model for the live performance was a museum tour, whereas the model for the video was not the museum tour so much as the introductory videotapes that museums were starting to make about themselves in the ’80s to sell in their gift shops. My favourite example of the genre was a video called Masterpieces of the Met with Philippe de Montebello. It’s really quite an outrageous artifact. It’s Philippe de Montebello in his double-breasted suit, with his hard-to-identify European accent, performing his connoisseurship. That was the reference, and I was thinking about how the video could then exist within that field as a kind of intervention. Then the script was prepared for publication in October with 55 footnotes, which I also conceptualized, in part, as an intervention in the context of an academic publication.

There are also three versions of Untitled (2003), aren’t there?

Yes. There’s a 60-minute-long silent, unedited video document of the collector and me in a hotel room having sex. Then there’s a version modelled on ’70s performance documentation, which is a print with six video stills, an installation photograph and a press release. I generated that version because I was getting a lot of requests by people who wanted to show the video and I had developed a policy not to loan the video for group exhibitions. I’ve made a couple of exceptions and I always regretted it. But there were serious exhibitions with very thoughtful curators and so I wanted to provide some way to represent the piece in the context of those shows. Then there’s a third manifestation of the project, which is a 10-minute audio piece.

Little Frank and His Carp (video still), 2001, SD video.

In which you leave in your sound but take out the sound of the collector?

That’s right. The video was shot in a way that would make it cold and distant and render it a kind of conceptual document. It is a wide shot from the corner of the room and there’s no camera movement. When it was first shown, people were complaining that it wasn’t sexy because they were expecting pornography, which it isn’t. The audio is the opposite in some ways. The audio is intensely intimate. It actually feels much more voyeuristic than the video. It’s a very textured, dense, evocative room tone, with sounds emerging that you’re straining to catch. It’s like making eavesdropping spatial. With the video, even though it’s not at all explicit, you’re given an image. But with the audio, you’re imaginatively projecting yourself into a soundscape.

Untitled was made in 2003 and there was a lot of hostile nonsense written about it. How do you feel about it now?

It was a tough time because the response was very disappointing. But the part that was the most difficult was the prurient obsession with the price the collector paid. That was something that I very naïvely did not anticipate. In my mind, it became the crux of the piece. The collector had to pay something and that he paid money was conceptually an essential component of the work, but the specific amount was not conceptually important. And anyway, what he paid was much more than the cheque he wrote because he paid with his body and his participation in taking a risk and exposing himself.

You pointed out that the idea of prostitution was raised, but extortion could more easily have been a factor. Here’s a married guy sleeping with another woman.

Yes, that’s the bad joke I’ve made. I found out only after the fact that he was in the process of getting a divorce. In reality my role was less that of a prostitute than of a pornographer. What was really essential to the piece, both in terms of my experience of doing it and conceptually, was that I was producing a commodity I would own.

Little Frank and His Carp (video still), 2001, SD video.

You go in conceptually and the audience goes in transactionally. If you see it as a transaction, then the idea of price inevitably comes up.

The obsession with the price captures so much of what the art world is about. It’s the pornography and the spectacle of the price. That’s what we get at auction season every year. But we know that there’s a very intimate relationship between sex and money in any circumstance, not just in connection to prostitution or pornography. The other painful part was that the circulated price, which I told the New York Times was not correct but they published anyway, was then paraded as cheap. Putting myself in the position of a price being attached, not just to my work but, vis-à-vis the metaphor of prostitution, to myself, to my body, my person, and that price being considered cheap, was incredibly painful. Although it took a few years, it certainly contributed to my decision to leave the art market, which I did in 2011. That was the outcome of a seven-year-long process of trying to resolve the very contradictory position that I put myself in. When I refer to the piece today, one of the things I talk about is what it revealed for me. What it revealed is the profound difficulty that most of us have in separating our sense of self and individual value from the value that we’re given within various markets for our labour or for the products of that labour. I think that difficulty plays a central role in the ever-increasing income disparity in competitive job markets, and in the hyper-inflation one finds in highly competitive markets, including the art market. Of course, the art market is manipulated at a certain level to always go up, and we know exactly how it’s manipulated. But the way so many people get caught up in the competition of what our value is within the labour market is central to the functioning of capitalism in almost every field. Even when we might be critical of that capitalist mechanism, we still participate because it’s tied to our sense of self-worth and value.

Welcome to the Wadsworth: A Museum Tour, 1991, SD video converted to HD video, colour, sound, 26 minutes 12 seconds. Photo: Alex Yudzon. © Andrea Fraser.

One of the most appealing things about your work is how much you are in it, how much we see of your vulnerabilities and your hesitancies and self-doubts. The work is about institutional structures, and it knows how to create distance, but it’s also so much about you. It makes me wonder how conscious you have been in working yourself into the work.

Well, I would say that it’s not about me as an individual. It’s about where psychological and emotional structures intersect with social and institutional structures. It’s about reflexively engaging with that point of intersection, which means starting from my own experience. But I think that often gets broken down into just critical distancing or a kind of autobiography. For example, Museum Highlights is often written about as parody and seen as irony. Those terms imply the operation of critical distancing and even a kind of comic distancing. And it has funny moments. But I think what makes it meaningful is that there’s also a lot of pathos. There’s not just my critical distancing of the docent figure, but, to use what was a dirty word in my circle at the time, there is “empathy” for that figure, a sense that I’m also finding myself in her position. That other pole was there from the beginning and it was there for a few different reasons. One was because I did study acting and I read Stanislavski when I was in high school, I was exposed to method acting and to some of the basic principles of psychological realism, so I didn’t come to performance only through Brecht. It is also connected to my childhood growing up with a psychotherapist. And it is connected to feminist consciousness-raising practices of examining one’s psychological and emotional entanglements in systems of oppression. All of that contributed to my sense of the value and the importance of the emotional and the affective, the recognition that we’re not just subjects who are produced by institutions through discourses and through mechanistic social structures, but we’re subjects who bring to those institutions desires and fantasies and dreams and emotional lives. Those emotional lives are central to our relationship to those institutions and why we invest and participate in them. And it is through those investments that institutions reproduce themselves. Working between conceptualism and feminism and between Bourdieusian sociology and psychoanalysis is always about trying to find the point of intersection between emotional and financial economies, between the personal and the political, the subjective and the social. An analyst who wrote a lot about empathy, Heinz Kohut, characterizes it as “vicarious introspection.” That’s how he understands the observational method of psychoanalysis. We can’t know the psychological and emotional life of another person through our external senses. What we know we can know only through a form of empathy in which we project ourselves into the experience of another. This corresponds to the research that I do. My work swings between extremes of pseudo-social science, sociological, economic and political research, on the one hand, and often highly exposing psychological investigations of desire and emotional investments and conflicts, on the other. I think both are always in my process, and my most successful works are the ones in which that intersection is really available for the viewer. I’m also dealing with my own experience. We spoke earlier about how artists sometimes exploit actors or performers. In some ways, I was doing that with Jane Castleton. I created her as a “not me” container for aspects of my own relationship to museums that I didn’t want to own. She is a container for my own class aspirations, my own desire for legitimacy, my own desire to be recognized and to be held by that institution, which I wasn’t able to recognize because I also felt so dominated by those institutions. Putting those parts of myself in that container allowed me to look at them from a certain critical distance. But I think the success of the piece is that I didn’t completely disown them. The performance holds my connection to those things in the form of empathy. Ironically, in a sense, I am not empathizing with “her” but with the parts of myself I projected into my own construction. The performance wasn’t just a matter of theatrical technique but was also an enactment of the psychological and sociological structures I was grappling with. Bourdieu has this phrase that I really love. He got it from Bachelard, but he talks about “the particular instance of the possible.” You can do autobiographical work that closes phenomena down, or you go in the other direction. Yes, I’m an individual and I have a particular experience, but it’s just a particular instance of what historically and socially and psychologically it is possible to be. I’m trying to work from that point but with all the conditions and forces that intersect where I am, not to close it down but to open it up. The point of working from that point of experience is that from there you can activate and connect with the internal experience of others.

Welcome to the Wadsworth: A Museum Tour (video still), 1991, SD video.

At the end of your work Model Homeowner, the guy asks you, “Are you confident about your future?” Let me pose his question in a less obnoxious way and ask if you’re confident about the future of art and your place in it?

Well, I just joined Marian Goodman, a gallery that’s been the guardian of conceptual traditions and many of the artists and art practices that I looked to since I was a young artist. I have come to feel confident that I won’t be forgotten, at least. Am I optimistic about the art world? I don’t know. For a decade I was saying that my most optimistic scenario for the art field was that it would completely fragment into increasingly autonomous subfields. That was the time when I wanted to operate in the public sphere and in the academic context as an artist without having to deal with what the art market represented. I thought you’d have the market field, you’d have the exhibitions field, the academic art field, and the extra-institutional DIY field of community-based practice. Well, that fragmentation didn’t happen. The gap between what is sold and valued in the art market and what is shown in museums, if not collected by museums, has gotten bigger and continues to diverge. But many of the battles I was fighting in the ’80s and the ’90s, and even in the first decade of this century, have been entirely lost. It’s not like the trajectory wasn’t obvious starting in the 1980s. Since then, the art field has become a massive culture industry, and the art market has become a financial sector. I don’t see anything like the historic avant-garde or even the neo-avant-garde existing anywhere in the world. Other forms of community practice have emerged, particularly in the context of post-colonial and decolonial struggles, and I think they carry some of the politics and the autonomy of historical avant-gardes. That remains my reference because it’s what I developed out of. But it’s a completely different world from the one I entered in the 1980s. I do feel a sense of personal loss and a sense of political loss. But there are also amazing developments and possibilities, like the wave of unionization in museums and universities across the United States. Right now at UCLA there are 48,000 graduate student workers on strike. That organizing activity represents a significant shift in the field. It’s a consequence of neo-liberalism and of the degree to which museums and universities are functioning like corporations. Those of us who engage with those institutions are no longer seeing ourselves and our relations to those institutions only through the lens of cultural capital and sublimated intellectual interests. I don’t know where the fight for equity within those institutions will end up. But I think it’s a tremendously important and positive development. Also, reckoning with White supremacy and the legacies of colonialism within North American institutions has unfolded in an amazing way in the last couple of years. I think it is starting to lead to important structural changes. ❚