Portraits of Ephemerality

At each exhibition of the works of Colette Whiten, I think again of the opening sentence of Theodor Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory:” It is now taken for granted that nothing which concerns art can be taken for granted any more: neither art itself, nor art in its relationship to the whole, or even the right of art to exist.” Whiten does not take anything for granted—not what to make, how to make it or even why it should be made in the first place. She seems continually to reinvent art.

This profound level of questioning the nature of artmaking itself is what makes her “an artist’s artist.” It’s not that all her work is profound or successful, but all her work does arise out of a continuous and unrelenting struggle to come to terms with the dilemmas of living in the 20th century. Her work is not about the nature of art, but about inventing a way to deal with the issues that engage her as a human being in this place, at this time.

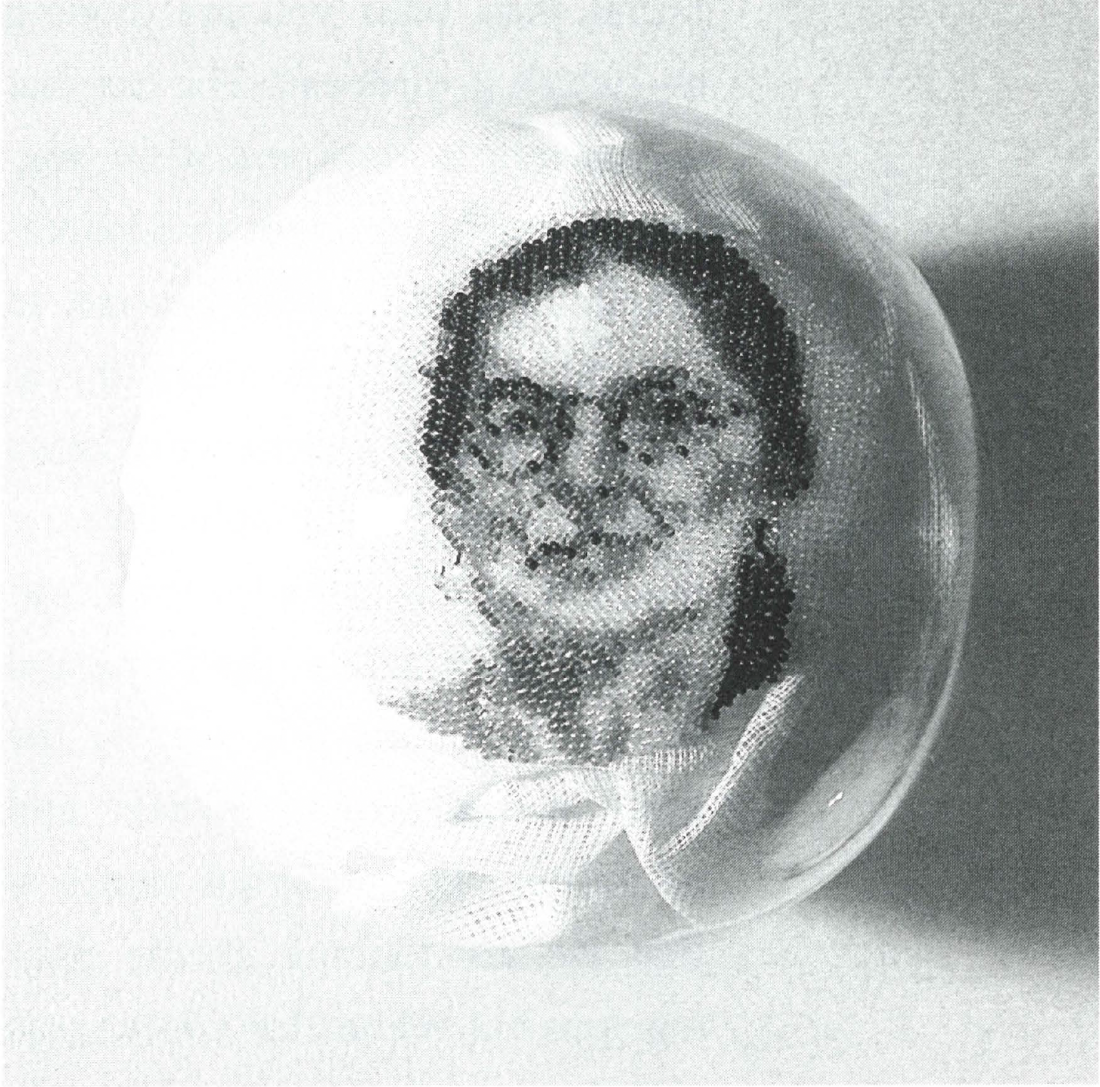

One of the concerns in her most recent exhibition, at the Susan Hobbs Gallery, is the portrait. The genre is a very old one in the history of western art but these portraits are unlike any I have seen before. She has created images of colleagues and friends out of black, white and grey beads sewn onto cloth. Her previous works with beads were free-hanging curtains of various sizes, some more like fringes and others up to seven feet high and perhaps six feet wide. The new ones are sewn on cloth and look at first like her earlier petit point black and white images taken from newspaper photos of major political events. Each portrait is circular, about five inches in diameter, and placed in the type of globular bowl used for terrariums or small plant conservatories. These are mounted on the wall and from a distance look like eyes with the portrait being the iris. Not, of course, eyes in a head but individual eyes fastened to the wall.

Obviously a wall of eyes is very disconcerting but as you approach you focus on the faces which are, so to speak, in the eyes. It’s as if you could see what the eye is looking at rather than what you are looking at—which is a portrait. The fact that the portrait is black and white suggests strongly its origin in a photograph. As I went from portrait to portrait I realized how ubiquitous in our society is the experience of being looked at by photographs. We are watched by our grandparents, our parents, our children, the living and the dead. We are followed by the gaze of politicians, models and celebrities. The accepted stance is that we are looking at the photographs but Whiten has cut through to another more uncomfortable reality: we are the ones being looked at. We are looking at an image looking at us in an eye looking at us.

Colette Whiten, Colette from “I Witness,” 1996-1998. Courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto.

Colette Whiten has, as far as know, no particular interest in Zen but these new works are very close to visual koans. The closest parallel I can think of is a recent work by Nobuo Kubota, called The Mute Raven, in which a raven and a camera face each other. The raven’s eyes are ball bearings and reflect the camera; the camera’s lens is a mirror and reflects the raven. We come to stasis, but feel tantalizingly as if we are on the verge of realizing some profound truth.

The way Whiten has chosen to exhibit these portraits has to be accepted as her statement but other ways of seeing these objects are possible. The first time I saw them was in her studio where they were attached to steel strips mounted on bases which projected the images out at the viewer. The portrait itself was stretched much like a piece of embroidery on a round frame and the rest of the cloth simply hung down. They were like small spirit people or slightly threatening puppets. They brought to mind depictions of the transference of Christ’s face onto Veronica’s veil, or that extraordinary self-portrait of Michelangelo in the The Last Judgement which hangs down as stripped skin. What is most striking in her final choice of presentation is how she has moved from this earlier, more theatrical presentation to a deeply felt concern with the contemporary and personal experience of these portraits.

One of the most commented upon characteristics of Whiten’s work is the laborious process of its execution. Much has been written on the emerging and often dominant role of process in 20th-century art; most commentators on Whiten’s recent work have given some postmodernist or feminist importance to her choice of processes—they are domestic, traditional women’s arts or fragmentary. These attributions make for interesting speculation but there seems to be two truths—the truth of the theorizing and the truth of the actual art work. Whiten herself uses the phrase “harmless busywork” in regard to her choice of processes. This phrase indicates how focussed she is on the issue. Her processes are downplayed in comparison to the immense and overwhelming importance of the image or issue. In exactly the same way that thousands of events and images stream past us every day until we no longer can judge the important ones from the unimportant, so the “harmless busywork” does not warn or prepare us for the moment when she stops the clock and invites us to really see the world that is flowing over and around us. We are plunged from “harmless busywork” into confronting the truths of our everyday living. It is as if the soft veil of reality has been torn aside to give us a sudden view of the human drama concealed behind its gentle folds. As she says, almost innocently, “I am making images which cannot be accommodated by conventional methods.”

The beaded portraits presented in ocular-like globes are only half the exhibition. Upstairs and completely separate from the main gallery are shelves of these same portraits etched on zinc plates. At first these highly polished images look as if they might be a documentation of a part of the production process for the portraits in the lower gallery. The images etched on metal are from the patterns used for constructing the portraits out of beads. The graph-paper grid and the reference lines can be clearly seen. In another way, and more importantly, they are a transmogrification of the portraits into totally different obJects. These objects are, I think, about ephemerality. The portraits of colleagues and friends become secondary to the silvery patens themselves. In fact, from a distance you can see that they are portraits but as you approach they seem to disappear into fragmented lines. The patens become almost like a filigree to the point where it is difficult to convince yourself that you are not actually looking through them. Again references occur—the engraved bronze mirrors of the ancient Mediterranean cultures, the patens used at Mass—but as soon as you step back, the portrait reasserts itself as contemporary. I wondered as I looked at them if they would have a different impact were the same portraits not shown in the other gallery. I don’t think they need the reference; they are another manifestation of the images but not a dependent one.

It is now more than 15 years since Colette Whiten began her black and white petit point works depicting or redepicting major political events. They were portraits of world leaders, rebel leaders, grieving women, rendered painstakingly in small stitches—high tech electronic images in low-tech, hand-produced objects. In the early ’90s she began working with beads, giving full, freestanding scale to images similar to the ones she had used in the earlier petit point works. Gradually, she moved into texts, taken from newstories, such as Paul Bernardo, and then to those small critical phrases with which we try to excuse or straighten out our lives: “Help it, I can’t help it.” Her focus is unrelentingly on the serious and critical aspects of our lives, which she explores with the most seemingly harmless of techniques and materials. Her new works push the process into dilemmas that are intensely personal without losing the realization that we are inherently part of a complex contemporary society. ♦

Colette Whiten’s exhibition ran from December 3, 1998 to January 30, 1999 at Susan Hobbs Gallery in Toronto.

Terrence Heath is a Toronto-based writer and critic. He recently curated an exhibition for the Kelowna Art Gallery of the work of Nobuo Kubota called “The Exploration of Possibility.”