“Pop Life: Art in a Material World”

As a teenager, I saw an Andy Warhol film, the name of which now escapes me. However, I recall the setting was seedy, the actors emaciated, the quality grainy and dark, and the plot almost non-existent. I remember the lateness of the summer night, the chair in which I sat, and my position in a room adorned with the casualness of youth, languishing barefoot on sofas. The film’s tangled narrative, its sleaziness, its confused bohemian dreamers and their (dis)ability to imagine a trivial task into something momentous, some decadent time-consuming endeavour was to me at the time nothing short of thrilling.

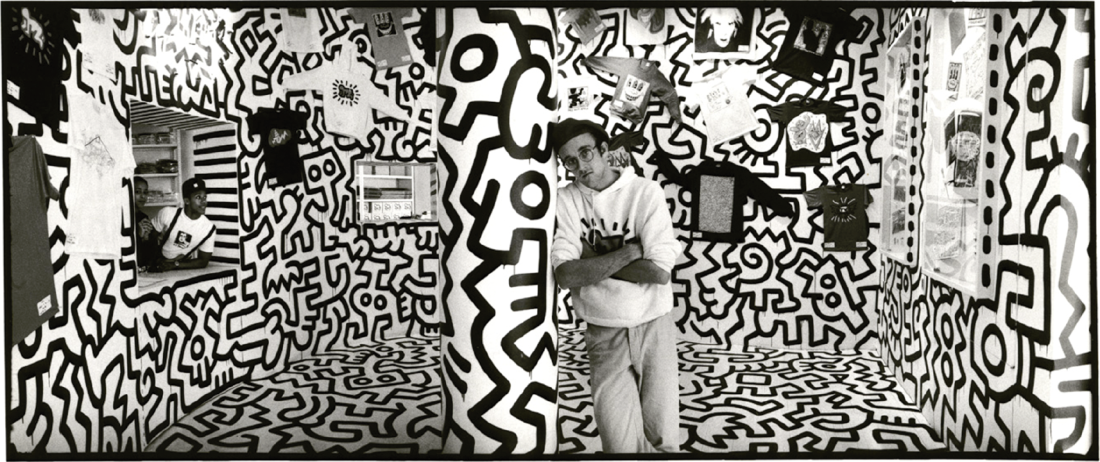

Keith Haring, Pop Shop, 1986. Photograph: Charles Dolfi-Michels. © Keith Haring Foundation.

For me, then, National Gallery of Canada’s Director Marc Mayer’s description of “Pop Life: Art in a Material World” as an exhibition that allows one to “look at the present as if looking at the past” seems apt. It is a show that, through some latent familiarity with many of the works (not too mention the heavy ’80s feel to some of the rooms), created a sense of nostalgia and allowed for a comparative viewing—then and now.

Historically speaking, Pop art has made pop culture nervous—a certain self-conscious suspicion tells us we are being mocked and not celebrated. We seem to begrudge the Pop movement its prophesying of our immediate incarnation of popular culture, which is, among other things, excessive, obscene, celebrity-obsessed and occasionally tacky. It is curious that we should point fingers at Warhol or Jeff Koons for being manipulators, as this seems to exempt society’s participation in the building of the machine that drives Western culture, which once resembled a ready- made and now takes on a slicker, faster form. However, a clearer reality than the vilification of Pop art and the artist is the possibility that culture is so thoroughly distracted by the very fodder of Pop art that it can wager no opinion past neutral on the subject. So engrossed are we with the minutiae of celebrity, so convinced are we that one’s media persona is authentic and consistent with “real” life, so constantly entertained are we that we can no longer find the objective distance within which to judge, let alone recognize, art.

Jeff Koons, Flash Art International, November/December 1988, advertisement. Photograph: Tate Photography, S Drake. Courtesy Flash Art.

Much has been made of the show’s potential to offend; however, aside from the odd pornographic close-up, there was little of significant shock value for any modern media consumer, to whom sensationalist disclosure is common practice and discretion an archaic concept. Furthermore, some of the more scandalous pieces that appeared (if only momentarily) at the Tate or Hamburg did not appear in Ottawa, notably, Richard Prince’s Spiritual America, a photograph of a nude, prepubescent Brooke Shields (replaced by an adult bikini clad version of Shields posing in front of a motorcycle). As well, on request of the artist,Andrea Fraser’s video piece of her arranged and paid for sexual encounter with an art collector was not on display.

“Pop Life” is presented chronologically, beginning with Warhol and ending (more or less) with Takashi Murakami. This is not the Warhol of the Brillo Boxes but rather Warhol of the ’70s and ’80s, after his shooting in 1968, at which point a sharpened interest in celebrity emerges. The format of the entire exhibition was based on the concept of mise en scène, whereby each room recreates important, controversial or scandalous moments in the lineage of Warhol—some rooms being more successful than others. The recreation of Keith Haring’s Pop Shop in the middle of the exhibition, with music blaring and t-shirts and other memorabilia being sold at inflated prices was, if anything, unexpected in the normally austere environment of a national gallery. However, the Pruitt and Early room felt a little awkward (which may be exactly the point). As well, due to the sheer number of works in the exhibition, it felt at times that pieces were crammed into every nook and cranny. Prince’s Spiritual America seemed as though it was hung in a foyer entering the house of Koons. The volume of work did make it difficult to take in everything, but I think, contextually, this also made sense. “Pop Life” would not work if it were sparse—just as does consumer culture, it includes all the things we need and, more poignantly, all the things we don’t. For this reason, it is a show likely best enjoyed in multiple visits.

Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger, 1975, acrylic and silkscreen ink on canvas. Private collection. Photograph: Tate Photography. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / ARS (New York) / SODRAC (Montreal).

The exhibition afforded the opportunity to view particular works, which are in themselves the stuff of self-made myth. It is a treat, for example, to see Damien Hirst’s unicorn suspended in pure fantasy, which serves, too, as a precursor for another equine encounter of equal power in Maurizio Cattelan’s untitled piece of a taxidermic horse. Also of note is the re-creation of Hirst’s Ingo, Torsten as Twins Performance, in which the artist has invited 70 sets of identical twins, identically presented, to sit in front of his trademark spot paintings. Aside from the organization, Canada’s contribution to the show is through the inclusion of a handful of works by General Idea.

There is an awful lot of glitz in the show, so I found appealing the works of Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas, in that they were suggestive of the low-tech roots of Pop art. Also sharing this room was Gavin Turk, who is probably one of the more understated of the Pop stars. On the opposite end of low-tech manufacturing is Murakami, whose room was bright, energetic,the work slick and highly manufactured. In the final room, following Murakami, were the Reena Spaulings’s tablecloth pieces. Although their placement does seem logical, they are overshadowed by the excitement of the previous room and the work itself seems more conceptual than Pop.

“Pop Life” is an exhibition that, as co-curator Catherine Wood states, “is a way of rewriting our understanding of the realm of representation, and the power it holds, via its basis in economics.” It is, at times, an intelligent and energetic show that caused one to consider, among others, issues of identity, appropriation, economy and authenticity. Furthermore, it challenged us to define not only “what is art” but to consider by which parameters will we determine its success. And what would Mr. Warhol have to say about all this? Well as it happens, Andy, the prophet, answered the question before it was asked: “Don’t think about making art, just get it done. Let everyone else decide whether it’s good or bad, whether they love it or hate it. While they’re deciding, make even more art.” ❚

“Pop Life: Art in Material World” was co-curated by Jack Bankowsky, Alison M Gingeras and Catherine Wood and was exhibited at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa from June 11 to September 19, 2010. “Pop Life” was also exhibited at the Tate Modern in London from October 1, 2009, to January 17, 2010, and at Hamburg Kunsthalle in Germany from February 12 to May 9, 2010.

Tracy Valcourt lives and writes in Montreal.