Playing the Fiddle While the Amazon Burns

Art in a Time of Climate Crisis

Nothing makes an artist feel as ineffectual as the looming climate catastrophe. Its existential pragmatism makes short shrift of poetics to focus on questions like: Who is financing the art and where does their money come from? How much waste is produced from the invitations, posters and flyers? What is the environmental impact of the all show accoutrement—the temporary walls, the climate-controlled rooms—of which the artwork itself is just the tiniest element? No matter which message is embedded into a work’s impasto layers or montaged into its video frames, art’s critical potential is all too frequently undermined by its relationship to luxury and symbolic capital. This makes its intentions as discomfiting as the mewl of Nero’s imagined violin, though now is it the artist who fiddles as the Amazon burns?

The myth of Nero playing the fiddle before a blazing Rome shows how effectively an image can transform into a legend and create templates for collective cultural imagining. This is as risky as it is seductive, causing many artists to question the power of sensuous experience, while others still use it as a rhetorical tool. Group shows organized around the topic of environment are particularly suited to illustrating this bifurcation, like last year’s “The Garden of Earthly Delights” at Gropius Bau, Berlin. Though theorists like Timothy Morton have argued for the necessity of direct, even “intimate” aesthetics in response to climate change, it was precisely the most sensuous of works that proved the least convincing. In contrast, artists favouring a pragmatic and active, if not explicitly activist, approach are redefining the role of art.

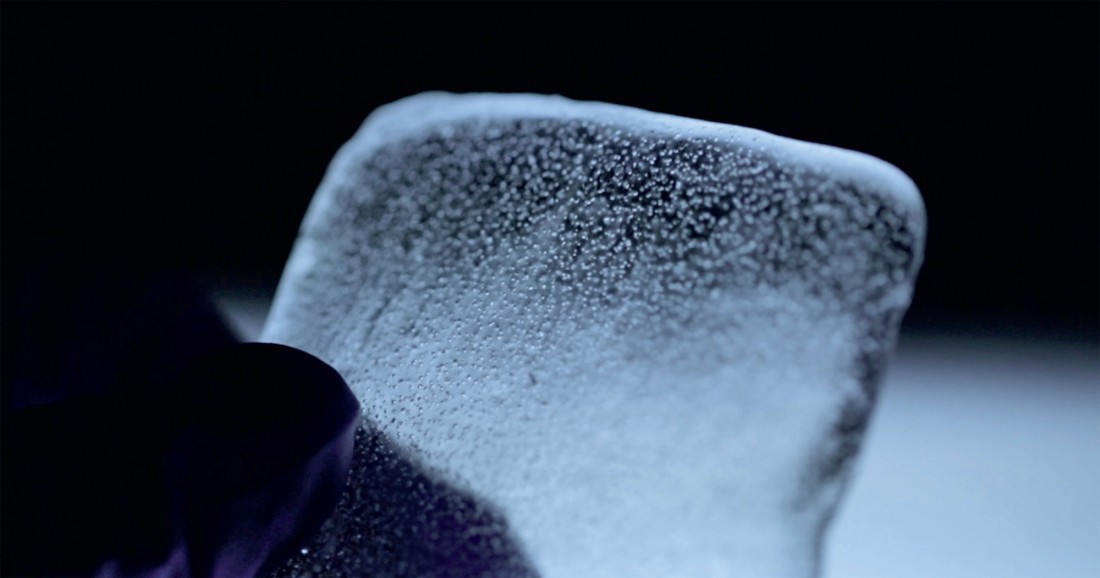

Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing, Ice Watch, 2014, 12 ice blocks, City Hall Square, Copenhagen. Photo: Anders Sune Berg. © 2014 Olafur Eliasson. Courtesy of the artist; neugerriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles; and Studio Olafur Eliasson, Berlin.

When asked if she sees a trend moving away from the aesthetic in art, Stephanie Rosenthal, director of the Gropius Bau and curator of “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” responds with an adamant “no.” The sensuous quality of art makes it powerful, which in itself has little to do with the problems and contradictions of the art world. Artists have always been one step ahead of institutions, contends Rosenthal. Collaborators and eco-art movement pioneers Helen Marie and Newton Harrison are prime examples. They were making work about climate change in the ’60s and ’70s, but the art world wasn’t ready to hear the message. Today, it has no choice but to listen.

Rosenthal’s response to the crisis is two-fold. On a practical level, the Gropius Bau is committing to avoiding flights within Germany, building on-site as much as possible, reducing exhibition architecture and curating exhibitions in response to climate change. “The Garden of Earthly Delights,” despite its celebratory title, poached from the middle panel of the Hieronymous Bosch triptych, 1535–1550, which forms the centrepiece of the show, presents the art against a backdrop of “radical climate change and migratory flows,” as per the exhibition’s didactic material. The works of the 21 included artists and art collectives narrate a cultural history of the garden—garden as idea, strategy, technique, etc. By starting with a man-made structure, the show’s main accomplishment was to expand the notion of the climate crisis beyond the strictly ecological, so as to highlight the economic and colonial inequalities that drive resource exploitation. Rather than digging deeper into this, or any one direction, the exhibition offered something for everyone—religion, eco-politics, hedonism, to name some of its topics—and in doing so illustrated how the reception of art is changing over time.

The backdrop of climate change served to cast a number of big names in a less than flattering light. One example was Yayoi Kusama’s giant urethane painted flowers, With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever, 2013–2019. The installation was meant to invoke the classic Kusama effect of bodily disorientation, a sensation often described by Timothy Morton in the art he admires. Not only did it not disorient, it trivialized the topic with its plastic material excess. Pipilotti Rist’s ambient video installation Homo Sapiens Sapiens, 2006, felt dated in its oversized, kaleidoscopic portrayal of two naked white women climbing trees and taking “pleasure in every detail of their surroundings” by intermittently squeezing overripe fruit between their breasts and thighs. Its allusion to a primal state of the desiring feminine felt anachronistically essentialist, its teasing evocation of ripe plentitude already dubious for its time. Explicitly political installations, like that of Jumana Manna, also stumbled into an interpretative cul-de-sac. The artist showed two works together, one aesthetic and the other documentary. Wild Relatives, 2019, is a video depicting Syria’s displaced agricultural research centre’s attempt to regrow its lost seed supply with imported specimens from the Global Seed Vault in Norway. Arranged around the projection was a collection of ceramic sculptures from her “Water-Arm Series,” 2019. Next to the video, the vessels went largely unnoticed. If anything, they were like burial offerings or funerary urns, as if aesthetics were already relegated to the position of archaeological artifact.

Jumana Manna, Wild Relatives, 2018, film still, 64 minutes HD video. Photo: Marte Vold. Courtesy of the artist.

Jumana Manna, Wild Relatives, 2018, film still, 64 minutes HD video. Installation view, “Garden of Earthly Delights,” 2018 Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin. Courtesy of the artist.

Yet, it is precisely a sensual approach that some argue is needed not only to change our mind but our entire perception of reality. This is how Olafur Eliasson explained to The Guardian (Tim Jonze, 2018) why he transported massive ice blocks from Greenland, despite the environmental cost, to spectacularly melt in Europe’s public squares. Timothy Morton, in his 2013 book Hyperobjects, has gone so far as to theorize this approach. Hyperobjects seem to be the latest in a conceptual history that includes Lacan’s “Real” or what Kant theorized as the “monstrous”—the thing beyond the sublime that has no place in the realm of aesthetics. In Morton’s ontology, they denote complex thing-events that people cannot comprehend because they inhabit an expanded spatio-temporal realm. An encounter with a hyperobject, examples of which include black holes, atomic bombs and global warming, is supposed to be an uncanny experience, partly because it is technically impossible. When their presence indirectly impinges upon us, and here is the opening for art, their utter strangeness makes us feel foreign to ourselves. Object oriented art, according to Morton, is precisely what is needed to help people confront that which can’t be understood. Through the use of what I would describe as “affect,” it bypasses epistemology to wade directly into the sticky ontological sludge. Like the strange, chilling beauty of Eliasson’s foreign ice chunks, it alone can disrupt our understanding of, or rather our gut feeling about, existence itself.

Less successful are what Morton calls “constructivist approaches.” They are lamed by their reliance on information. They ask us to cognitively grasp the ungraspable—to memorize, compare and reason. What art needs to provoke, suggests Morton, is an intuitive reaction akin to when we might see a truck barrelling toward a toddler in the middle of the street. We wouldn’t, or shouldn’t, first weigh the pros and cons but fling ourselves into the path of imminent danger in order to rescue the child. Morton’s account is seductive precisely because art can act like a life-changing lightning strike, while reason deliberates over time. The lightning bolt of realization, however, is far from guaranteed, and were it always progressive, many arts funders, like BP or Unilever, would long since have changed their business practices. We should also not dismissively relegate bad taste to bad people, a knee-jerk reaction sometimes used to criticize the art of the former Soviet Union. Stalin himself is said to have liked Mikhail Bulgakov’s work, though he found it too dangerous to publish. Meanwhile, the former dictator’s trademark architectural style is no longer considered gauche. A prime example is Warsaw’s once-hated Palace of Culture and Science; today, it is a protected heritage building. Things start to get even trickier when art mixes with dangerous ideas, something it has historically reserved the right to do. Could Steve Bannon’s favourite novel, The Camp of Saints by Jean Raspail, have evoked the uncanny shudder of another impossibly opaque hyperobject—the dark swelling of non-English-speaking third world migrants?

Susan Schuppli, Learning from Ice, Part I: Ice Cores, 2019, HD film still (ancient air bubbles captured in Antarctic ice). Filmed at the Oregon State University Ice Core & Quaternary Geochemistry Lab. Courtesy of the artist.

It’s not surprising that many artists are choosing a constructivist approach. Renzo Martens, known for pseudo-exploitative videos dramatizing the art world’s pernicious colonization, has started a project in which he uses art world structures to help Congolese plantation workers buy back their land. Artist and filmmaker Edgar Honetschläger has gone so far as to found an NGO and devote himself to environmental activism. Indigenous film collective ISUMA’s ambitions do not seem to lie in the art world, though they use it as a financial support to produce televisual programming for their northern community. Institutional critique is morphing into institutional action. In this growing, if not entirely new, development, art is no longer a universal ideal but a question of pragmatics.

A particularly good example of this is the work of Susan Schuppli, whose project “Learning from Ice (Part I: Ice Cores),” 2019, was exhibited at last year’s inaugural Toronto Biennial of Art. In a telephone conversation she explained to me that cultural institutions are not the sole context for the dissemination of her work, but they do come with a number of practical advantages. Among them is a trans-disciplinary openness that allows knowledge to flow freely, rather than remain the sole domain of experts. Another is the fostering of alternative strategies in order to narrate a different conception of the world. In contrast, organizations like courts of law or the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change might come off as conservative. Their claims are, by necessity, empirically based for the purpose of advancing solutions rather than raising questions, which is a role traditionally associated with the arts. That, however, is changing.

Susan Schuppli, Learning from Ice, Part I: Ice Cores, 2019, HD film still (ancient air bubbles captured in Antarctic ice). Filmed at the Oregon State University Ice Core & Quaternary Geochemistry Lab. Courtesy of the artist.

Susan Schuppli, Learning from Ice, Part I: Ice Cores, 2019, HD film still (Athabasca Glacier Columbia Icefield). Courtesy of the artist.

The second part of Schuppli’s multi-year project is driven by a proactive approach. While “Part I: Ice Cores” consists of two documentary videos—one featuring interviews with ice core scientists and the other offering a glimpse into the daily activities at two ice core research facilities—part two is conceptualized as an “ice law” forum. This will be a symposium where invited speakers present ideas and debate how climate change and law mutually influence each other in the Circumpolar North. At stake is how thawing permafrost, glacial melt and changing sea ice are transforming not only the ecosystem but Indigenous ways of life, national boundaries, trade routes and access to resources. The goal is to rethink the relationship between law and ice, something neglected in existing conventions, in the hope of influencing future policies.

Schuppli’s process is a creative interrogation into how we conceptually organize our world. Ice cores, for example, are what she calls “material witnesses.” Rather than being imprints of material processes, like fossils, they contain actual evidence of global warming: minute traces of ancient air that give scientists a direct glimpse into the past. Because atmospheric particles circulate over the entirety of the globe in the course of a year, evidence for all airborne events is deposited into the polar ice. This means that the ice not only records the extent of pollution but also allows deductions into the effectiveness of environmental policy, the use of chemical weapons, the conducting of atmospheric nuclear tests and more. As ice cores are analyzed, they are transformed into what Schuppli calls “social objects for making public claims,” which can directly impact policies and political decisions. Conceptualized as social objects, you can begin to ask, what rights might a material object have in a court of law? Can a material object be granted equal say amongst other stakeholders?

The move towards explicitly proactive approaches does not wait for an undefined public to be “inspired” to take “climate action,” as Eliasson said he hopes to do in the press release for Ice Watch Paris, 2015. It uses the art object, and the art world, as a tool for action rather than unpredictable personal change. This might also be said of much of today’s art writing, which rarely focuses on the art itself but on the politics and conditions of its presentation—conditions that have led to a number of high-profile artist protests in the past year. It’s thus apropos that 2019 ended with the Turner Prize’s being split four ways. The rationale was that a single winner from the four socially engaged artists would wrongfully privilege one form of politics over another—a reason that clearly indicates, despite the enduring hierarchy of the market, a change in the way art is seen and judged.

Perhaps instead of asking what art can do in a time of global warming, we should ask another perplexing, if not as urgent question: what does global warming do to art? I’d like to suggest that it strips it bare of its mythos. It instrumentalizes and literalizes it in response to the disappearance of a mainstream conception of truth. The result is a return to objectivity without the former imperial arrogance that passed off Eurocentric bias as fact. This is an objectivity of grim inevitability — a very effective equalizer — and it’s changing how art is valued and understood.

The article above appeared in a slightly different form in the print issue, no. 154. What appears here includes the corrected conclusion. (Revised June 2020)