Pieter Hugo

A man stands defiantly with one bare foot resting atop the body of a dead bull. The animal’s throat has been slit. A chunk of its innards is slung over the man’s shoulder. Dabs of blood drip from his eyes. He wears a rumpled suit and tie.

The image, a photograph called, Gabazzini Zuo. Enugu, Nigeria, 2008, is collected as part of “This Must Be the Place,” South African photographer Pieter Hugo’s retrospective at the Hague Museum of Photography. The photo possesses qualities that unite it with the rest of Hugo’s work: a blunt exhibition of African “otherness,” a stark sense of drama and a confrontation (or is it collusion?) with the racism historically encoded within Western representations of people of colour.

Zuo, the subject of the bull photo, is a makeup artist working in Nigeria. “Nollywood,” the nickname for the second largest film industry in the world (ahead of the US, but behind India), is also the title of one of the photo series on display. Hugo’s work here plays with the iconography of Nollywood films, which often depict violent situations involving religion or the supernatural. The photos might also be seen as obliquely nightmarish visions of modern African history. In one, a woman stares out from the frame with a bloody machete stuck in her belly. In another, children made up to look like skeletons hang out in vague industrial zones.

Pieter Hugo, Gabazzini Zuo. Enugu, Nigeria, 2008, from the “Nollywood” series, digital C-Print, 68 × 68”. Images courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

Should Hugo, a white South African born in Cape Town during apartheid, be taking the photographs that he does, for public consumption in trendy international galleries or on hip art blogs? Should we be looking at them? The exhibition in the Hague sits within the administrative heart of the country whose rule produced the apartheid regime and countless other atrocities. Are the eyes of the museum’s patrons also turning inward as they take in Hugo’s spectacle? Or is an encounter with these political sensitivities part of what he is trafficking in—the transgressive thrill of revisiting the old, now-forbidden ways of looking at the other?

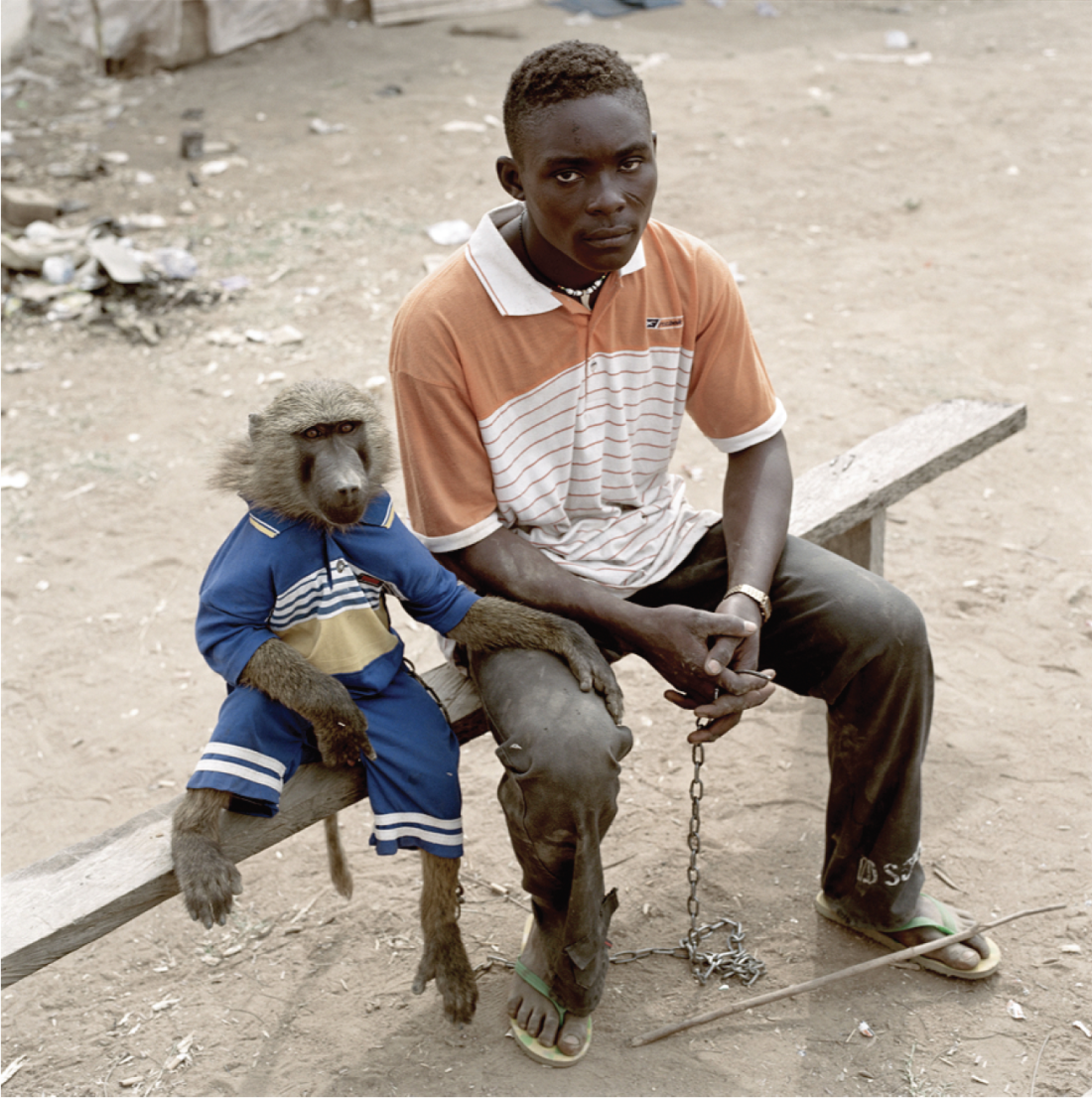

Hugo’s most compelling photographs are those that offer a complex matrix of character, documentary and subtle jabs at the viewer’s fetishizing gaze. The series “The Hyena & Other Men” depicts a band of entertainers consisting of several trained hyenas wearing braided muzzles. In a few of these photos, the hyena tamers assume poses of strength and dominance over the ferocious looking animals. In another, a little girl lounges on a sleeping hyena that doesn’t seem to care. In yet another, a serene-looking monkey sits next to its keeper, one arm placed tenderly on the man’s leg. With their novelty these photos draw the viewer into a subculture little-known outside of Nigeria. The subjects recall colonial portrayals of African men and their customs, but the series rewards deeper looking through the stories and emotional textures contained within the interplay between the people and animals.

Not all of Hugo’s work adds up in quite the same way. A small section of the gallery is devoted to broader African subjects: “Vestiges of a Genocide,” macro- photographs of physical objects and human remains from the Rwandan genocide of 1994, and “The Bereaved,” close-ups of the faces of men who have died of AIDS. The topics of these series feel too big and too raw for Hugo’s camera to find purchase. They are larger conversations—worthy of whole shows, multiple artists, varying perspectives—and as a result feel undeveloped next to the more hermetic realms of Hugo’s other work.

Dayaba Usman with the monkey, Clear, Nigeria, 2005, from the series “The Hyena and Other Men,” digital C-Print, 68 × 68”.

The last section in the show at the Hague is in the farthest, brightest room in the space devoted to Hugo, and it is perhaps the most remarkable. “Permanent Error” depicts the boys of a market in Accra, Ghana who are collecting electronic waste for the resale of selected component parts and the extraction of precious metals. The portraits play to Hugo’s strength for composition and drama and his journalistic eye for a story. And here his preference for titling his portraits after the exact names and coordinates of his subjects falls fruitfully in line with a political goal: specifying the people and places that some would have us forget. Gone is the co-opted pageantry of “Nollywood” in favour of a muted, naturalistic color palette. The photographs of the boys, who go about their labour with dignity in a space without it, are as moving as they are galling.

In interviews, Hugo claims that growing up in apartheid South Africa was a period of clearly defined rights and wrongs. The joyous end to the regime produced an aftermath, still ongoing, of political and cultural uncertainties. Hugo’s gaze encodes this confusion, warts and all, in an assemblage of images, tones, and subjects as heterogeneous as the continent itself. ❚

“This Must Be the Place” was exhibited at the Hague Museum of Photography in the Netherlands from March 3 to May 20, 2012.

Robert Kotyk is a writer based in Winnipeg.