Philip Guston

“Philip Guston: Works on Paper” at the Morgan Library is a small, powerful exhibition that traces Philip Guston’s relationship to ink, graphite and gouache across the last 35 years of his life. The first part of the exhibition charts Guston’s mid-career abstractions. In drawings such as Untitled, 1958, and Untitled, 1946, staccato lines repeat, filling the entire, yellowing surface of the paper with inky punctuation; other works in which loose, calligraphic scrawls fill the frame like exuberantly unwound balls of string seem less sensical. For nearly a decade, from the late ’40s to the late ’50s, Guston’s line, whether quick and cross-hatched, heavy and careful, or slight, as if an afterthought, seems to bask in fundamental questions: What can line do? What is its relationship to the edge of the paper? How can it change? What effect do those changes have?

Philip Guston, Untitled (Cherries), 1980, ink and acrylic on board, 20 x 30”. Private collection. © Estate of Philip Guston.

By the mid- to late-’60s, his exuberance is re-channelled and fine-tuned into near-object studies. Wave II, 1967, is of a single, black, slightly meandering line that cuts diagonally across the page. The few, short, evenly spaced lines of Air, 1967, are indeed air-like, with the spaces between drawn as much as their visible counterpoints. With Full Brush, 1966, Prague, 1967, and Head, 1969, among others, the slow seeping-in of subject matter, narrative, allusion and illusion—dirty words to any Abstract artist—is blatant. Renderings of clocks, books, webs and paintbrushes, objects that would become canonical for Guston, emerge, with line breathing life into these everyday things. The hands of his clocks arc and bend far beyond the clock’s face, and the same black lines seem to scream joyously with new significance; his short staccatos are repurposed to signify text on his book pages. Following Guston’s transition into these tangible, unexotic objects is a delight, as if watching the unfolding of spring—albeit one occasioned in his life’s autumnal phase. Though each phase could be seen as dramatically different from the other, the unchanging fact of drawing, in its economy and forthrightness, is what ensured its crucial place in his practice. “It is the bareness of drawing that I like,” he once explained. “The act of drawing is what locates, suggests, discovers.” At one point, Guston equated this bareness to a tabula rasa, abandoning painting in favour of drawing for several years to incite a re-discovery.

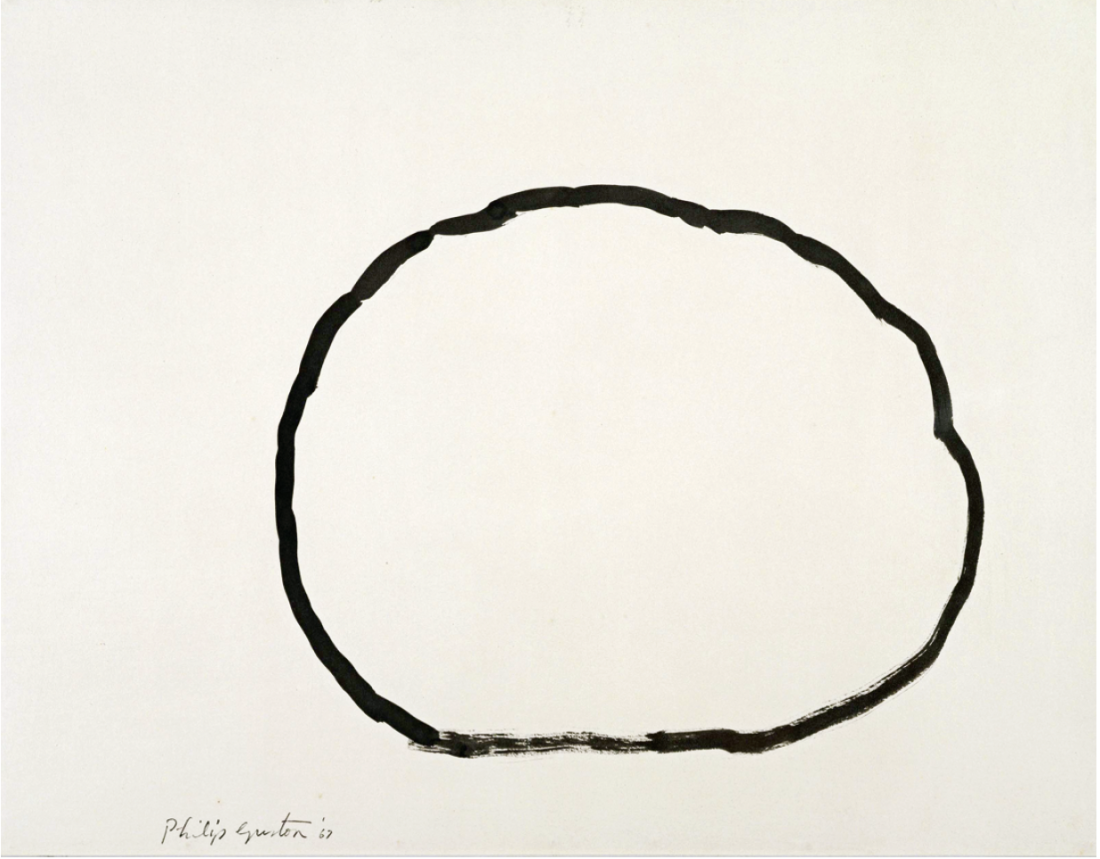

Philip Guston, Untitled, 1967, ink on paper, 17 ½ x 22 ½”. © Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy McKee Gallery, New York. Photo: Sara Wells, New York.

The floodgates open in the early ’70s: Cyclops, cigar-smoking hooded figures, giant hands, webbing, his “Poor Richard” caricatures of Nixon, and baconand- egg sandwiches are given full reign in what Guston himself described as “leaping out of the world and into the imagination.” Untitled, 1970, depicts two hooded figures, done in charcoal, smoking giant cigars. Smoking in Bed I, 1974, assumed to be a self-portrait, depicts a bulbous, cartoon- like figure tucked up to his chin in bed while wearing boots and draped in spider webbing. Throughout this period, illness, violence, anxiety—wrought by the Vietnam War and misguided American foreign policy—send Guston into a furious relationship with American junk. Crowning the decade is Fault, 1980, in which a severed Cyclops head languishes near an accumulation of brushes, shoes and dirt.

Philip Guston, Drawing Related to Zone (Drawing No. 19), 1954, ink on paper, 17 ½ x 23 ¼”. Private collection. © Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy McKee Gallery, New York. Photo: Michael Korol, New York.

One of the highlights of the show, and also one of the few works containing colour, is Untitled, Cherries, 1980. The plump, perfect-stemmed red cherries are piled high on some unknown horizon and buoyed by small shadow scrawls. The drawing epitomizes Guston’s continual refitting of reality while echoing the play in his earlier abstractions. As with many of his colloquial subjects, Guston’s cherries appear knowable, and yet floating on their beautiful, transparent blue ground and drawn in his unmistakable hand, they are everything but. ■

“Philip Guston: Works on Paper” was exhibited at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York from May 2 to August 31, 2008.

Julia Dault is a New York-based artist and writer.