Peter Hujar

Peter Hujar’s New York— ambiently ugly, poor, potholed— is easier to imagine as sound than sight. The chaos of metal in movement, of sirens infiltrating thin walls, of music pounding through new boroughs, prevails in memoria. Screams after blackouts, tides of street life. The New York of Charles Ludlam’s Theater of the Ridiculous, the Cockettes, the Fillmore East, the Fun Gallery, the back room at Max’s Kansas City, the Tenth Floor, Fire Island Pines, all pulse and seethe. The city rattles.

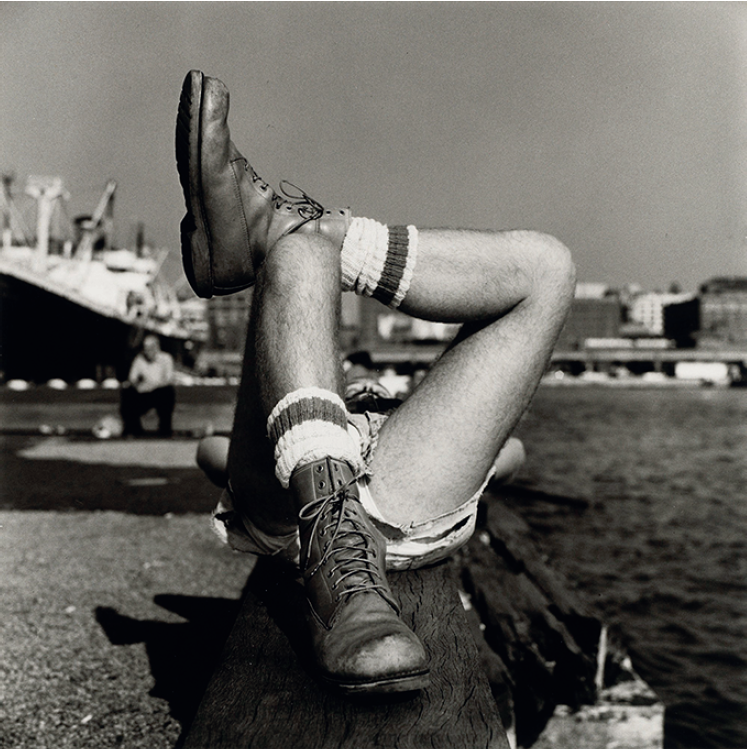

Then to see a Hujar image is to take refuge from the din. His record of time is one of condensed quietude. Black and white photographs, minimally composed, and so exactingly developed they glow gold, echo what Atget did for Paris in the 1920s. Like his, Hujar’s city is made up of the secrets hidden in plain sight: high-rises that resemble Wonka chocolate bars, caves beneath the piers, the dark swells of the Hudson River. Exterior becomes interior landscape.

Peter Hujar, Christopher Street Pier (2), 1976, gelatin silver print. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Hujar was largely eluded by fame throughout his life, and a holistic new exhibit of his work at the Morgan Library & Museum is aimed as a corrective. The most comprehensive survey of his work to date, the retrospective spans Hujar’s earliest work in the 1950s to his death from AIDS-related complications in 1987. Some of the 160 photographs have never before been shown. In bringing them together, the exhibition solidifies Hujar as one of the great American photographers.

Following a brief stint as a commercial photographer, Hujar settled into a semi-legal loft on Second Avenue, where he began photographing the downtown scene from his window. Portraits were his vocation. Famously, he photographed his friends and lovers—no one for whom he didn’t have great affection: Greer Lankton, David Wojnarowicz, but also bodies in the catacombs, a horse, an abandoned house, a boy with his hand on his enormous hard-on, looking at himself.

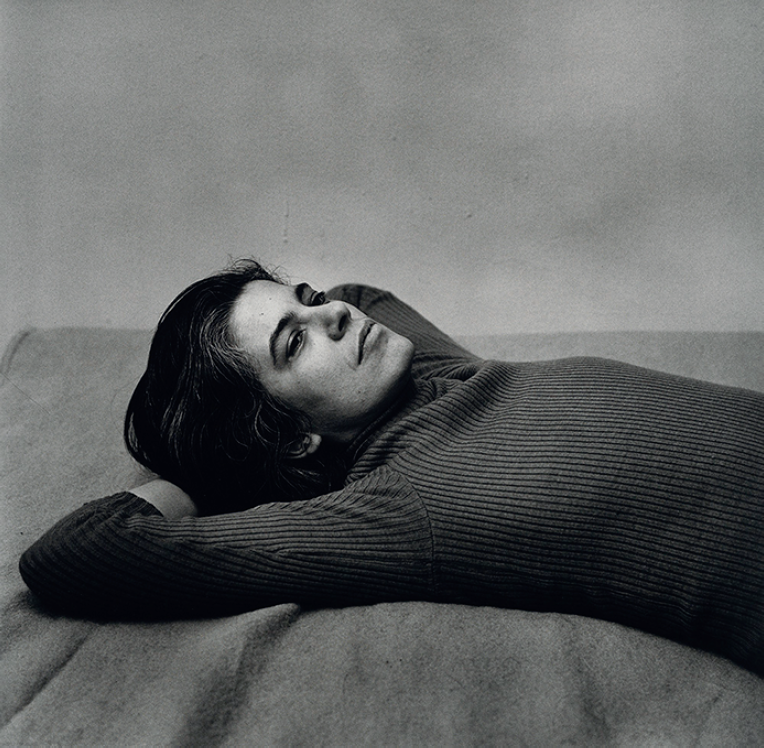

Photographed within his loft space or on house calls, his infamous subjects appear at rest in his hands. No strangers to being looked at, his coterie didn’t need to stare directly to understand they were being seen. Their bodies are sloped, uninhibited. They fall into positions only intimacy allows.

Gary Indiana Veiled, 1981, gelatin silver print. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Courtesy Pace/ MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

Obvious comparisons with Hujar’s rival and better-known counterpart Robert Mapplethorpe abound. Both explored themes of gay male desire, favoured square formats and were insiders among a circle of famous artists and writers. But while Mapplethorpe’s ice-cold aestheticism—his symmetry, his deliberateness—presents his subjects architecturally, that is, as objects, Hujar’s equally disciplined photographs imbue them with imperfect grace, as human. Less gaze and more attention, his portraits are a direct result of his feelings for his illustrated subjects. If absolutely unmixed attention is prayer, as wrote Simone Weil, then Hujar’s work is a church. One key difference between the two is material: Hujar printed his own photos, while Mapplethorpe did not. Whereas the shock of Mapplethorpe’s prints emerge partly from the piercing highlights and deep blacks, the emotional tautness of Hujar’s work lies in his luminous midtones.

Hujar seldom showed in his lifetime, and shunned institutional acclaim (“Peter Hujar has hung up on every important photography dealer in the Western world,” Fran Lebowitz remarked at his funeral). His minor curatorial feat was a 1986 exhibition at Gracie Mansion Gallery, in which he installed 70 of his photographs in two dense rows. A perfectionist, he endlessly hung and rehung this ensemble of works until he was satisfied with the attenuations in subject and form he’d sought to attain. A version of this installation is reprised at the Morgan, with 40 photographs tightly grouped together. The result is a swell: a simmering William Burroughs; a downtown loading dock that doubles as cruising site; an expectant donkey; an awkward self-portrait. The works foreground less a common visual vocabulary than a magnetism and sense of otherness that were distinctly Hujar.

Susan Sontag, 1975, gelatin silver print. © Peter Hujar Archive, LLC. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco.

While the exhibit is built upon these photographic pairings— clusters of four wrapped around two central walls—it’s the singularity of each work that provides the extraordinary acuity of the whole. In his most widely reproduced, and still startling, image, Candy Darling on Her Deathbed, 1973, the Warhol starlet lies stage right, gilded and adorned in her hospital bed, dying of lymphoma. In her playing, as Hujar would later write, “every death scene from every movie,” Hujar captures Darling’s finest performance. Vulnerable and vamped-up, giving the camera a come-hither look, Darling seems to supersede death, to rise above the sterile fluorescence of the hospital room. Not everyone can produce an icon.

Hujar said that when he died he wanted two graves, one for his body and one for his work. He knew he was good, knew his work was important; he did not know how, exactly. It’s time for us to take a long look. ❚

“Peter Hujar: Speed of Life” was exhibited at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, from January 26 to May 20, 2018. Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, texts by Joel Smith, Philip Gefter, Steve Turtell and Martha Scott Burton, copublished by Aperture and Fundación MAPFRE, 248 pages, hardcover, $42.50.

Janique Vigier is a curator and writer based in upstate New York.