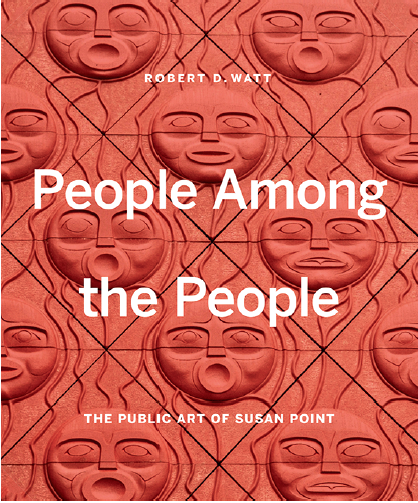

“People Among the People: The Public Art of Susan Point”

It is hardly news that Susan Point, a Coast Salish artist of the Musqueam First Nation, has almost singlehandedly recovered her people’s graphic and sculptural traditions from obscurity. Critics, curators and art historians have been observing this for years. We have also noted that while Point’s art expresses Musqueam history, beliefs and cultural traditions, it is also highly innovative, pushing boundaries of form and medium and addressing contemporary social and environmental issues. Point was an acclaimed printmaker before becoming a much sought-after sculptor in cedar, bronze, glass, granite, laser-cut aluminum and Forten, a kind of polymer. Her precedent-setting impact on younger Salish artists is unquestionable. I have often mused that it is difficult to imagine what contemporary Coast Salish art would look like without her.

People Among the People: The Public Art of Susan Point, by Robert D. Watt, Figure 1 Publishing, 2019.

Written by historian, archivist and former museum director Robert D Watt, People Among the People is a big, handsome and comprehensive survey of Point’s public art—and again confirms her significance. “Susan Point has played perhaps a larger role than any other artist in reinvigorating traditional Coast Salish art, which for years had languished in the collections of a limited number of museums,” Watt writes. “Her expressions and explorations of the Salish aesthetic have given it new life.” Covering 85 works created since 1981, the book reminds us of the living presence of the Salish peoples, both within their traditional territories—on and near the southern coast of British Columbia and the northern coast of Washington State—and beyond. Watt’s extensive texts, accompanied by photographs, describe the forms, materials and history of each public artwork, along with the meanings Point has embedded within it. Much of the information is based on the artist’s notes recording the research she undertook and the concepts she developed through each commission. Watt supplemented hundreds of hours of interviews with Point with his own research, delving into a range of archival sources.

This is not the first major publication focused on Point’s career (previous books include Susan Point: Spindle Whorl, the catalogue to her 2017 survey exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery), but it is the first dedicated entirely to her public artworks. These have ranged from tree grates and sidewalk medallions to house posts, welcome figures, stained-glass windows, carved glass panels, stone mosaics, low-relief sculptural murals, free-standing outdoor and indoor sculpture and architectural cladding in everything from cast concrete to polymer. Point’s commissions have come from band councils, municipal governments, corporations, developers, universities, museums, galleries, private foundations, cultural centres and recreation centres. One of her graphic designs, a streamlined Thunderbird, adorns Vancouver Police Department cruisers.

In her artist’s statement, which opens the book, Point recalls that when she began making art, “very few people were aware of the history of Coast Salish art and its connection to the community.” At that time, nearly four decades ago, the more northerly Indigenous art of the Northwest Coast was the “predominant style,” she writes, “probably because northern communities were less impacted by early contact.” Not only had Salish villages and cultural expressions been paved over by burgeoning cities, but also settler culture—whether represented by anthropologists, curators or collectors—tended to aesthetically privilege the art of the northern Indigenous groups. Point’s first creative undertakings were modest in form and scale: jewellery and screen prints, made at her kitchen table. Her desire to recover Salish form and style involved considerable research, through libraries and museum collections.

Susan Point carves the “Grandchildren” upright, part of People Among the People, 2008, in her studio at Celtic Shipyards in Vancouver, August 2007. Photo: Kenji Nagai. Courtesy of Archives of Coast Salish Arts.

Among the many facts and ideas forwarded in Watt’s book are Point’s recurring forms and motifs, including frogs, salmon and fishers, and their significance in symbolizing her social, cultural and environmental messages along with her sense of people and of place. Most significant—and most powerfully identified with Point—is the Salish spindle whorl, a key element in her “quest to revive Coast Salish art,” she writes. Originally consisting of a wooden disk with a hole at its centre, mounted on a tapered wooden shaft, this object was once used by Salish women when spinning yarn out of raw wool. In ancient and historic times, the whorl was carved on one or both sides with geometric, nature-based or figurative designs.

Point learned the formal components of Salish graphic design from studying spindle whorls in museum collections and adapting them to her two- and three-dimensional art. At the same time, she was honouring the spinning and weaving that had traditionally been “women’s work” in Coast Salish society. However, she quickly made the leap to “men’s work”—that is, large-scale carving—and one of her earliest monumental commissions is the immense cedar spindle whorl in the Musqueam Welcome Area at Vancouver International Airport. It is unendingly significant that Flight (Spindle Whorl), 1995, along with Point’s two large welcome figures, is the art that greets international visitors to Vancouver and British Columbia.

Other Salishan sculptural forms she has taken on include traditional house posts, which she has adapted to many locations. Watt is emphatic about the importance of Point’s three portals, People Amongst the People, 2008, located at Brockton Point in Vancouver’s Stanley Park. “This is a masterpiece in every aspect: concept, scale, execution, meaning, and aesthetic impact,” he writes. The highly symbolic portals mark the entrance to and periphery of the stand of famous Stanley Park totem poles, “the most visited tourist attraction in B.C.” Point’s portals also happen to be the first contemporary Coast Salish works installed by the City of Vancouver on that ancient and historic Coast Salish village site. All the previous poles sited there belong to northern Northwest Coast traditions.

The public artworks represented in the book are organized geographically rather than chronologically. This makes good sense culturally but leads to a degree of frustration for those more linear-minded of us interested in following the development and maturation of Point’s forms, styles and concepts. A chronology tucked into the end of the book would have been useful.

In her statement, Point writes that her art “honours both my people and the diverse group of peoples from around the world who have come to live upon our lands on the Northwest Coast. My hope is that my art leaves a lasting impression on visitors, locals, and the surrounding communities.” As for those of us living on unceded Coast Salish lands, we can only be grateful for Point’s talent and grace. ❚

People Among the People: The Public Art of Susan Point by Robert D Watt, Figure 1 Publishing and the Museum of Anthropology, UBC, 2019, hardcover, 248 pages, $50.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and contributing editor to Border Crossings.

To read the rest of Issue 152, order a single copy here.