Paul Wong

Some time in the past decade, it seems, Paul Wong pledged himself to beauty. The pioneering multimedia artist, who founded Vancouver’s Video In/VIVO in 1973, long ago established his reputation as a fearless and sometimes controversial explorer of sexuality, mortality and identity. His early, issue-driven videos intentionally eschewed slick camera work and mainstream aesthetics: they were raw, intuitive and, in many ways, confrontational. As Wong told journalist Adrian Mack in a Georgia Straight interview last summer, they were also about finding a place for himself (brash, gay, Chinese-Canadian) and his then-radical art form within the context of contemporary urban life.

Wong’s new videos, still photographs and neon, on view this past fall at Winsor Gallery in a high-end retail district of Vancouver, are elegantly composed, unabashedly lovely, and wryly self-reflexive. Some of this work locates itself on the charged interface between nature, culture and representation, articulating the silvery beauty of a full moon against a velvety black sky, the sound and fury of a tropical storm in Havana or the colour and form of a ginkgo tree in a classical Chinese garden. Issues of race, sexuality and marginality appear to have been abandoned in favour of Wong’s “marked turn towards the aesthetic,” as Kathleen Ritter observes in her illuminating exhibition essay. However, she insists, Wong’s recent interest in charting light and movement is not about renouncing the political nature of his previous videos, performances, photographs and installations. “In fact,” Ritter remarks, “these works make the case that formal and conceptual concerns in art are intertwined in complex ways.” She then adds that Wong’s life is in itself political—as is “the very act of hitting the record button on a video camera.”

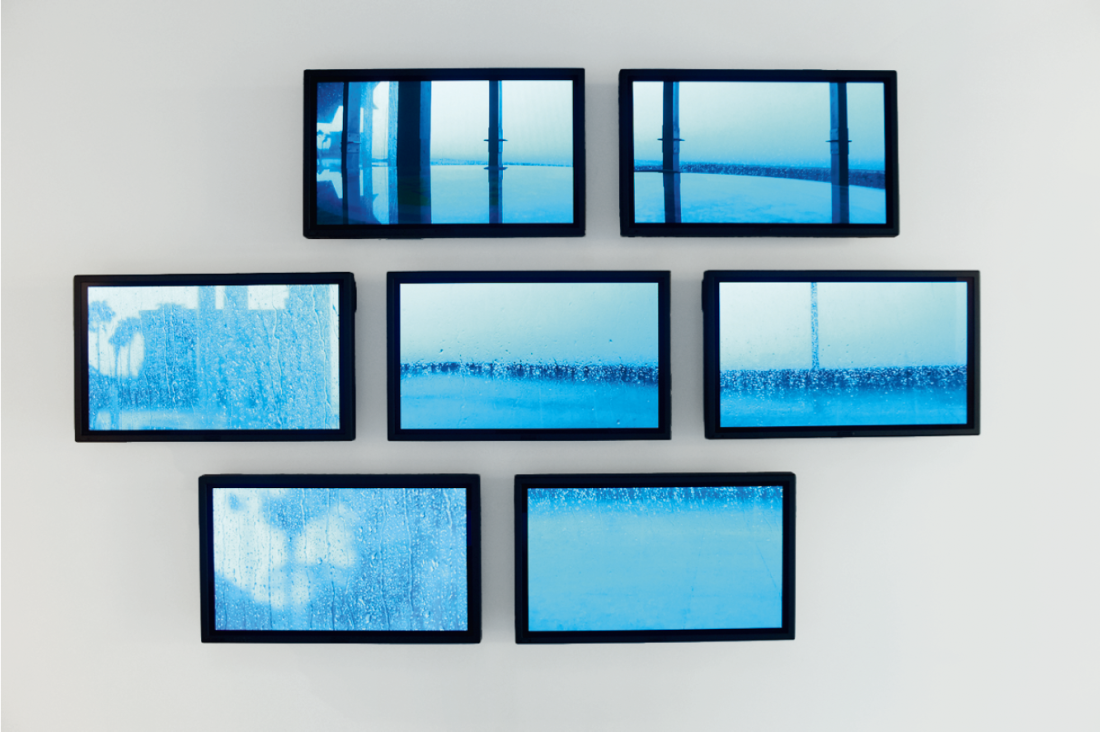

Paul Wong, Habana Riviera (Havana), 2011, edition of 5, 7 video loops of varying time with 22 minute soundtrack, 42” screens. Photographs: Jessica Bushey. Images courtesy Winsor Gallery, Vancouver.

The grid, with its minimal- conceptual connotations, was a recurring formal device in Wong’s Winsor Gallery show: photographic prints, neon marks and video screens were all mounted in orderly networks of verticals and horizontals. For instance, 21 Full Moon Drawings comprised three horizontal rows of seven framed photographs each. The individual photos, which depict the trace of a brilliant moon shining in a night sky, were taken with a still camera that Wong moved while shooting. The combination of this movement and the long exposure time have resulted in a print series of long, curving calligraphic marks realized in glowing light, each mark surrounded by a purplish aura against the surrounding darkness. It’s as if Wong had reached up and dragged the moon itself across the sky, then recorded its eloquent trail of luminescence.

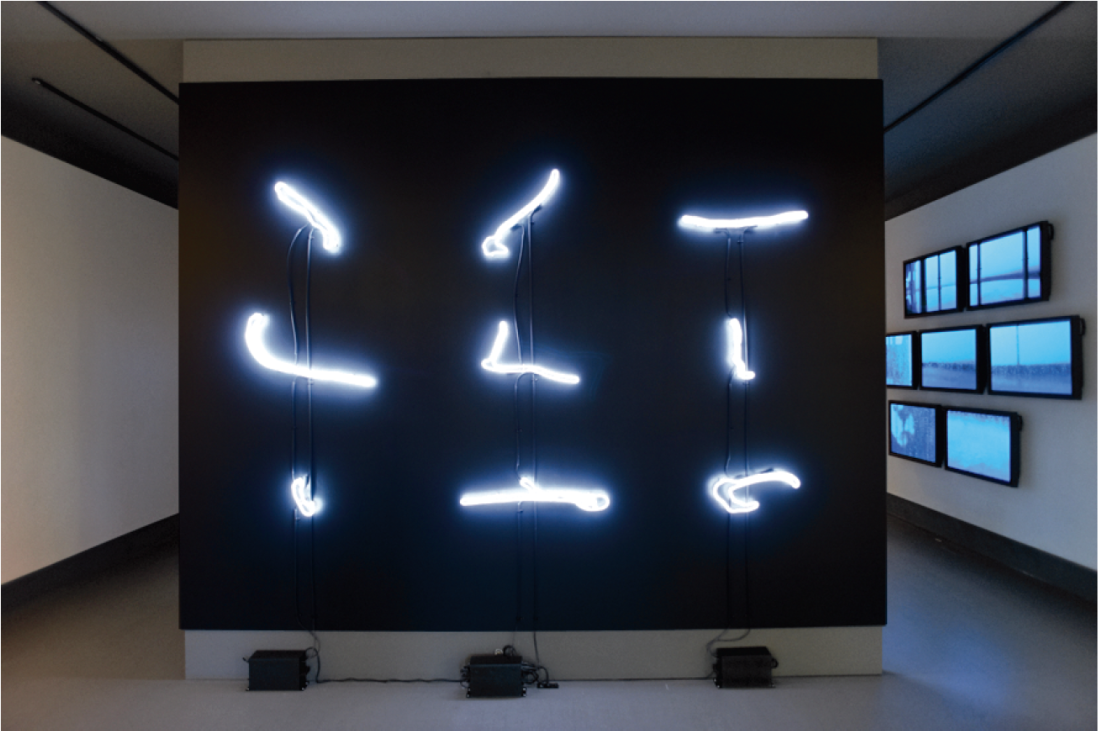

In this work and other smaller, but related, grid-formatted photos (some printed white on black, others printed less effectively in black on white), Wong makes literal photography’s most enduring metaphor—that of drawing with light. In so doing, he creates images that marry a kind of phenomenalist realism with Abstract Expressionism, and that equally entangle the work of a mechanical device with the work of the hand. In another embodiment of this poetic conceit, Wong has produced an elegant, glowing version of the full moon photographs in sign-sized neon. Mounted in a three-by-three grid on a black wall, the white neon jots, dashes and swooshes replicate the moon marks in the photographic prints. Again, there is the likeness to calligraphic abstraction, but at a post-modern distance. White neon, it turns out, very effectively mimics the cold silvery light of Earth’s only moon.

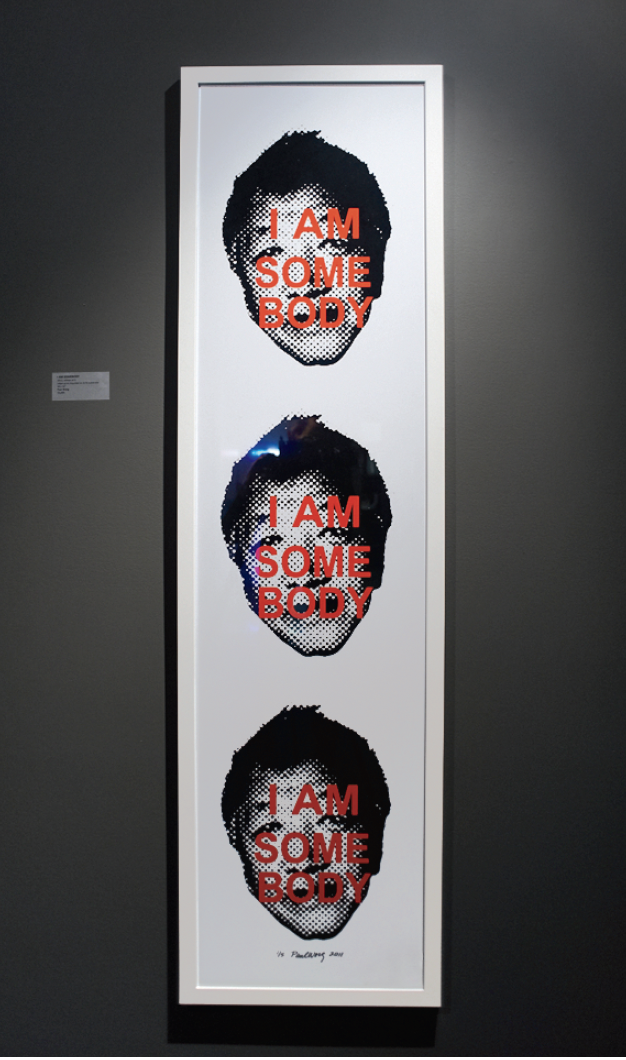

Paul Wong, I AM SOMEBODY, 2011, edition of 5, inkjet print mounted on 3/16 substrate, 64 x 16”.

The most arresting work in the show, a seven-channel video titled Habana Riviera, was shot from inside the luxury hotel of the same name, built on the Havana water- front in 1956 by a consortium of crooks headed by the American mobster Meyer Lansky. In January 1959, not incidentally, it was used as the site of a post-revolutionary news conference by Fidel Castro. The location of Wong’s looped video is therefore emblematic of a considerable history, both colonial and post-colonial. Running on seven screens mounted in three rows, Habana Riviera records, through the windows of the hotel lobby, a violent tropical storm. Palm trees thrash and bend in the wind; rain courses down the glass and floods the exterior courtyard; cars and trucks drive by on the Malecón, casting chevrons of water in their wake.

The colours in the video are washed-out monochromes—blues and pale greys—lending a ghostly mood to the event, and the sounds recorded during the storm have been altered to produce the eerily whooshing soundtrack. Together, the visual and aural effects are mesmeric—“richly immersive,” Ritter observes, “almost cinematic.” Gorgeously compelling as Habana Riviera is, however, it thwarts our expectations: we wait for the storm to abate, but it never does. Sound and image loop endlessly, and the suspense eventually exhausts us—as Wong must fully intend it to. And again, there is that historic subtext, that cycle of corruption, exploitation and revolution. The storm that never ceases.

An amusing aspect of this exhib- ition—Wong’s first show, ever, in a commercial gallery—was his investigation of his public persona. Signature in Neon is just that: a much-enlarged version of Wong’s signature, wrought in white neon and mounted like a nightclub sign on a black wall. It’s a cheekily egotistical echo of the neon version—the heavenly signature—of the Full Moon Drawings. Also on view was a trio of exuberant prints, in exaggerated dot-matrix format, of Wong’s face over-written with the words “I AM SOMEBODY,” and another series of prints, again of Wong’s face reproduced on a grid of Georgia Straight covers. The issue of the iconic Vancouver weekly that Wong uses as his portrait ground is one that features a photo of him, in cocky rock-star mode—defiant yet hip—on its cover. The hues used in these works deconstruct the way colour is broken down in the printing process (cyan, magenta, yellow, black), thus speaking to the inherently deconstructed and therefore artificial nature of representation. They also correspond with the breakup of colour in digital video (red, green, blue), as seen in another of Wong’s neon works, VIDEOARTVIDEOARTVIDEO, and in his four-channel video, Ginkgo, with its kaleidoscopic fracturing of form and hue.

Paul Wong, Full Moon Drawings Neon, 2011, edition of 5, neon, 8 x 10’.

The signs, signatures and self-portraits come across as part identity politics, part authorial self-satire (Postmodernism supposedly repudi- ates the artist’s cult of personality and erases signatures from artworks) and part gratified explor- ation of the long overdue rep- resentation by a commercial gallery. These works feel like the late-career expression of a creative outsider who, nevertheless, is immensely gratified by mainstream admiration and acceptance. Or perhaps Wong is having us on—spoofing these aspir- ations. (After all, he didn’t need the help of an art dealer to see his work placed in major public collections in Canada and the U.S. over the past few decades.) The curious braggadocio of I Am Somebody may also allude to the series of high-profile awards and prizes Wong has won late in his career, including the Bell Canada Award, the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts, the Trailblazer Expressions Award and the Transforming Art Award.

There may even have been a sly nod here to the ironic fact that, concurrent with his Winsor Gallery show, an abridged version of his highly controversial 1984 video, Confused: Sexual Views, was on view at the Vancouver Art Gallery in an exhibition titled “An Autobiography of Our Collection.” Once the subject of censure for its forthright and unglamorous discussion of sex and sexuality, once a symbol, too, of Wong’s outsider status, Confused has now taken its rightful place within his celebrated oeuvre. Beautiful though it is, I expect Habana Riviera will lodge there, too. ❚

“Paul Wong: Immanent” was on view at the Winsor Gallery, Vancouver, from October 13 to November 6, 2011.

Robin Laurence is a Vancouver-based writer, curator and contributing editor to Border Crossings.