Paul Butler

One late spring in the 1970s, my kindergarten teacher decided to suspend the normal curricular routines of 20 six-year-olds. Until school let out in June, instead of learning how to read and write, we would all be drafted into a major collaborative project: to build a classroom-sized model of our hometown, New York City. Divided into civic task forces of twos or threes (some friends and I were assigned the task of approximating all the city’s parks) we were to construct this Lilliputians’ Gotham only out of what we could scrounge or borrow or steal from our homes, and along the way we were to learn how to work together on a massive creative endeavour. What I mostly remember was a giddy sense of purposeful play and something like responsibility (a fragile state always threatening to devolve into anarchy and fits of tempera-clogged frustration, glue-fighting or interdepartmental jealousy), a miniature Babel-like endeavour resulting in something more collectively beautiful than any of us could have imagined.

Paul Butler’s “Collage Party”, ZieherSmith Inc., New York, June 2006. Photographs courtesy Paul Butler and ZieherSmith, NY.

I was suddenly granted a memory fix of this long-ago moment of communal creative mayhem one hot summer afternoon when a friend and I stopped by ZieherSmith gallery in Chelsea to check in on the week-long collage party being held there by the young Winnipeg artist Paul Butler and a group of 21 invited friends and acquaintances—both fellow artists from Winnipeg and various points across Canada (several related to Butler’s virtual online gallery, theothergallery) and likeminded New York-based artists associated with ZieherSmith. The word “party” suggests a lot of things, and knowing that Butler had mounted similar marathon rounds of art-making in places as far-flung as Toronto, Oslo, Berlin, Dundee and Los Angeles, I had come half expecting to find—four days deep into the event—a freefor- all, a gathering which would be fun and energizing for those involved, but perhaps a little scrappy on results. What I discovered, however, was a uniquely convivial and democratic creative workshop where everyone seemed fully committed to the task at hand with good-natured single-mindedness, an assembly of individuals clearly benefiting from the collegial/ competitive contact high of the resourceful energy around them. Everyone having hit their stride at one point or another by day four, a lot of astonishingly good work was piling up. One day before the opening, the room looked like a giant beneficent art bomb had been detonated just a few feet off the ground, scraps and odds and ends from every conceivable roughly two-dimensional source spilling from the long communal table and onto the floor, blending and recombining organically underfoot like one expanding, ever-changing automatic assemblage— archaeological wallpaper for the floor. It was so difficult to ignore the evolving mindless genius of the floor, scuffed and churned and pilfered for recycled raw ideas by one and all, that the gallery’s directors, Andrea and Scott, decided to leave this forensic evidence of the process just as it was for the following night’s opening. Over the month-long run of the show, these compelling leftovers remained, beaten, migrating on the soles of visitors’ shoes and slowly disappearing.

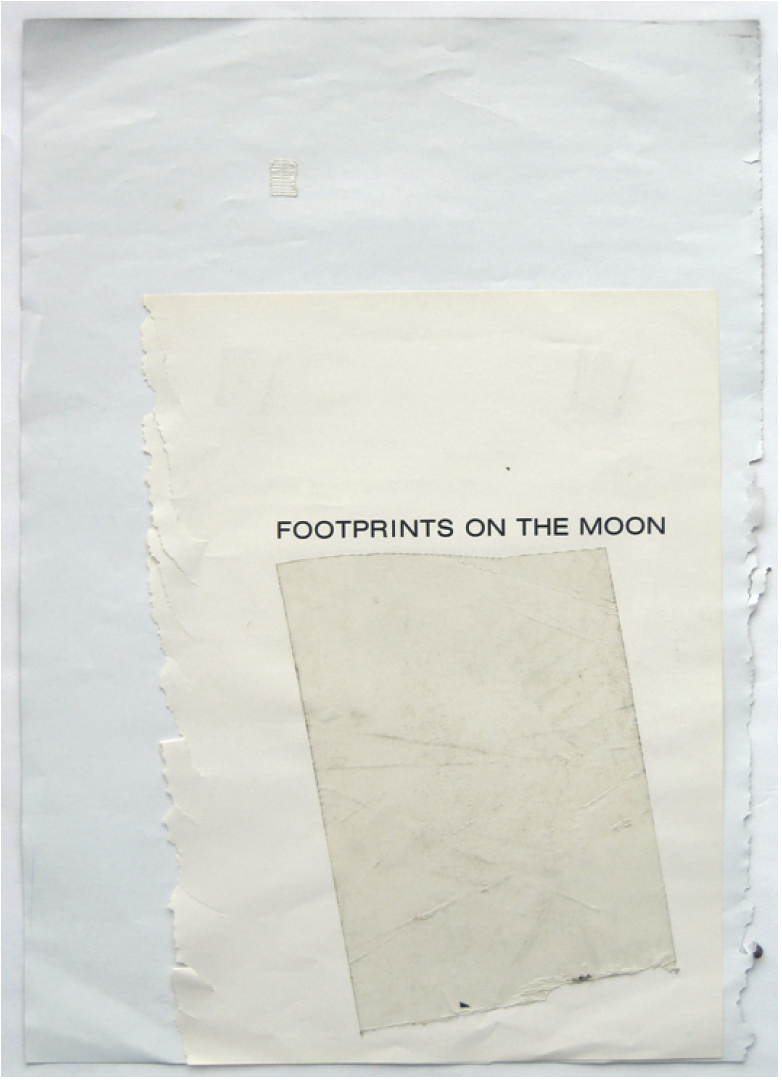

Paul Butler, Footprints on the Moon, 2002, collage, 12 x 16”.

Unlike other art world artist/ art facilitators, such as the Los Angeles-based architect and artist Fritz Haeg, whose Sundown Salon gatherings bring together creative types from different disciplines to make things together and share ideas in a tight social environment, Butler doesn’t bridle at the idea that his collage parties are anything more high-minded than a good excuse to get people together and have fun making art. In fact, they are demonstrations that fun, sociability and substantive art production aren’t mutually exclusive. (The Canadian contingent actually bunked together for the week at local student dorms, adding to the general atmosphere of a 24/7 sleep-away art camp). On this particular Wednesday afternoon, with everyone slap-happily scrambling to finish up before the opening the next evening, evidence of the productive results of autonomy within a collective enterprise was everywhere: At one end of the long wooden refectory table, punctuated with empty Pabst Blue Ribbon cans and bottles of soda pop, gluesticks and mat knives, artist Brian Belott was putting the finishing touches on a series of small colourful books whose bright pages were stiffer than the cardboard used for toddlers who’d rather chew on their reading material. The contents, however—non-linear, fragmentary arrangements of kids’ magazine covers, astronomical illustrations, wallpaper samples—read like primers for a language composed of patterns and textures. Three feet to his left, the Virginia Beachbased trio dearraindrop was excitedly exploring every over-the-top psychedelic cul-de-sac imaginable on a large assemblage that used an old Otis Redding LP cover as a starting point for a digressive series of rainbow labyrinths, candy-coloured hallucinatory forms and snappy Op patterning.

Paul Butler, Untitled (Flower), 2005, collage, 8 ½ x 11”.

On another wall, artist Tim Hull was modifying old National Geographic wall maps, finding ways for countries and colonial empires that no longer exist (the Belgian Congo, Tanganyika) to erupt into eye-popping territories of colourful fractal geometry. Elsewhere, other artists were dabbling in the time-honoured tradition of finishing one another’s work: In one collage, in a perfect handshake of minimalist bathos, Royal Art Lodge alum Michael Dumontier discreetly added a pair of accountant’s eyeglasses to Jeff Ladouceur’s woeful blobby boulder with a worn craggy face. The moody geologic portrait was pasted on a yellowed frontispiece printed with the matter-of-fact text at the bottom, “copyright 1940, by Garden City Publishing Co., Inc., New York,” a readymade caption explaining nothing while seeming to lend the image above its imprimatur of dumb actuarial legitimacy. In another sad-sack pairing, Californian Taylor McKimens and Brian Belott found common ground, the latter depicting a messy adolescent’s bedroom as a stage set for the former to paint ample volumes of his cartoonish R. Crumb-like blue goop bubbling and dripping off the bed.

At the opposite end of the table, Javier Piñón was tranquilly assembling his glossy photomontages. They harkened back to Richard Hamilton’s Brit-pop Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, 1953, and Martha Rosler’s charged Vietnam-era series “Bringing the War Home,” 1962– 1972, depicting roughriding rodeo cowboys cavorting and making slapstick trouble in posh, overstuffed domestic interiors of the sort found in the pages of Better Homes and Gardens or Architectural Digest, circa 1971. Directly across from him sat Montrealbased Shawna McLeod, inhabiting another world entirely, busy spinning out baroque graphic fantasias involving dragons, winged animals and metamorphosing flames, clouds, ribbons and wave forms.

Paul Butler’s “Collage Party”, ZieherSmith.

Through it all, Butler remained the calm centre of a high-intensity storm of activity, solving problems, providing jocular encouragement and giving a visiting CBC radio crew amiable sound bites and ample opportunities to record the sounds of busy scissors, glue sticks, staplers and background mood music (an Os Mutantes tape was on a boom box during our visit). His own contributions, like those of Dumontier and Adrian Williams, were characteristically restrained and minimally elegant, marked more by what they concealed and left unsaid than by what they actually showed. A new sampling of his ongoing plastic shopping bag series—pitch-perfect geometric abstractions that brought to mind the early Ellsworth Kelly or a more hard-edged, glossier Hans Hoffman—were less about the predominant collagist impulses of hungry accumulation, or the additive hording of images, or humorously discordant juxtapositions, than about the formal use of collage as an editing tool, a way of paring down a given assortment of things to their bare essentials. Coincidentally scheduled to coincide with the collage party in Chelsea, Butler was concurrently having his first solo show in New York at the downtown non-profit space White Columns. On offer there were a group of floral collages, pruned from various bridal magazines, in which one blossom gave way to another to create hybrids of unsuspected delicacy, surprisingly devoid of sentimentality or greeting card sweetness. As in the work of British artist John Stezaker, Butler was finding ways to elaborate on an Ernstian technique of nesting a collage within a collage, suggesting successive strata of visual and imaginative depth in the process. In the same room, he showed another work—a title page, presumably from a picture book published during the heyday of the space age, with the text “Footprints on the Moon.”

The paper, still retaining a slight antique sheen, was off-white heading in the direction of even greater profundities of off-whiteness; overlaid on its surface was a rectangle of dirty book endpaper, once pure but now showing its age. It was unclear if the scrap obscured more text or covered nothing; whether it added or subtracted.

Looking again at this image, I recalled that NASA recently discovered the famous missing “a” from Neil Armstrong’s first spoken words on the moon: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” For years it was thought that the astronaut had committed a lunar gaff, dropping the “a” before “man,” making his pronouncement an epically nonsensical pun memorized by millions of baffled schoolchildren. A painstaking analysis of the voiceprint of the two words on either side of the “a” (“for” and “man”) eventually determined that while the “a” was actually uttered, it was plucked out of the sentence by a wrinkle in the interplanetary radio transmission and spun out into the void of outer space, snipped forever from history. Considering Butler’s pale, mute blanknesses, covering up who knows what mysteries or banalities, one couldn’t help but think of that missing first letter of the alphabet, that tiny typographical free-floater falling away from our senses forever at the speed of light. ■

Paul Butler’s “Collage Party” was exhibited at ZieherSmith Inc. in New York from June 29 to August 11, 2006. Paul Butler exhibited in White Columns’ White Room in New York from June 23 to July 29, 2006.

James Trainor is Border Crossings’s contributing editor from New York and the North American editor for frieze.