Patti Smith: Making the Past Present

When many of us think of Patti Smith, we tend to think of one of two things. There is the Patti Smith on the cover of her landmark 1975 debut album, Horses, shot by her lover and lifelong soulmate Robert Mapplethorpe. In that photograph, a desperately skinny Smith stands, decked out in a loose white men’s shirt with its sleeves rolled up, thin tie draped down from her collar, jacket insouciantly thrown over her shoulder. The expression on her face is at once contemplative, cocky and intransigent, the background just a blank white wall slightly brushed with shadow. If Horses is one of the finest first albums in rock history, then the cover photograph is one of the most beautiful and evocative: here Smith is sensuous, romantic, edgy and somehow volatile. And then there is Patti Smith the furious possessed performer of the 1970s in storied venues like CBGB, part punk rocker part beat poet part shaman, shouting and spitting, whispering and purring her lines. “And when I look inside of your temple it looks just like the inside of anyone one man. And when he beckons his finger to me, well, I move in another direction, I move in another dimension,” she murmurs in “Ain’t It Strange” from Radio Ethiopia. “I was lost and the cost was to be outside of society,” she snarls in her controversial anthem “Rock N Roll Nigger” from her third album, Easter, a song that is about as close as Smith ever got to the confrontational iconoclasm of punk rock. “Jimi Hendrix was a nigger/Jesus Christ and grandma, too/Jackson Pollock was a nigger/nigger nigger nigger nigger/nigger nigger nigger…”

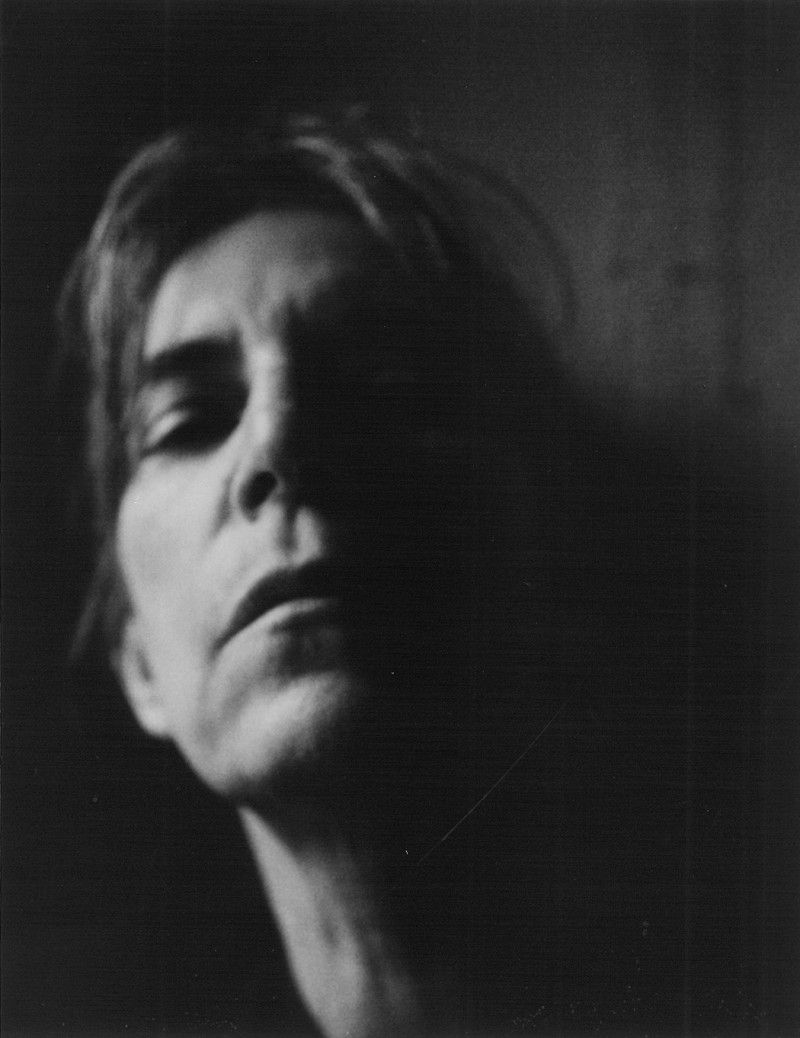

Patti Smith, Self-Portrait, NYC, 2003, Gelatin silver print, edition of 10, 10 x 8 in., 25.4 x 20.32 cm. All images © Patti Smith, courtesy the artist and Robert Miller Gallery, New York

The Patti Smith I encountered when she opened her hotel-room door in Ottawa this past November, while she was in the middle of a whirlwind, eight-city international tour with Neil Young and Crazy Horse, was hardly the frenzied, spit-spraying performer she was in the 1970s—and, incredibly, still is. Hotel room strewn with clothes and open suitcases, books and room service trays, Smith, who turned 66 in December, was clearly exhausted and distracted, her voice hoarse from too much singing and too much dry airplane air, and she was going on stage at the Kanata Centre in just a few hours. But once she plopped herself down in an easy chair beneath the room’s window, an early snowstorm blowing outside, put up her bare feet and pulled her long, tangled, grey-streaked hair from her face, she was suddenly focused and eager to talk, not about the old times at the Chelsea Hotel or CBGB, but about art, poetry, music and ideas. And when Smith talks, her voice low and insistent, her long, bony, beautiful hands fly, punctuating the rhythm of her speech.

Patti Smith’s 40-plus year career has been remarkable and in many ways wildly improbable, driven almost entirely by her innate fearlessness and the force of her sensibility. Born in Chicago, Illinois and raised in a working-class family in southern New Jersey, Smith moved to New York City in 1967 to become an artist and poet. She became a rock musician more or less inadvertently through performing her poetry with musical accompaniment and hanging out at Max’s Kansas City, but once she got going in earnest in 1974, her ascent was meteoric, and four important albums followed in quick succession: Horses (1975), Radio Ethiopia (1976), Easter (1978), and Wave (1979). But after five years of relentless performing, Smith had fallen in love with the former guitarist for the Detroit proto-punk band MC5, Fred “Sonic” Smith, and was ready to give up the rock and roll lifestyle to raise a family. The Patti Smith Group’s final performance was in Florence, Italy in the fall of 1979; when Smith arrived in Florence, the first thing she did was hit the streets in search of Michelangelo’s unfinished Slaves. Soon after, Smith was married and had moved to a quiet life in the suburbs of Detroit, where she lived in semi-retirement for 15 years.

Patti Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe, Chelsea Hotel, 1969, 2008, Gelatin silver print, edition of 10, 8 x 10 in., 20.32 x 25.4 cm.

When her husband died suddenly in 1994, Smith revived her career and moved back to New York, and her re-emergence has, if anything, been more spectacular than her initial rise. There have been six studio albums, including the critically acclaimed Banga, which was released last year and contains some of her most powerful work since Wave. There have been books of poetry, like the ruminative Strange Messenger, 2003, and Auguries of Innocence, 2005, and the heartbreaking memoir of her friendship with Robert Mapplethorpe, Just Kids, 2010, which won the National Book Award for non-fiction. And there have been major exhibitions of her work as a visual artist: “Land 250” in 2008 at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris, which included work she made from 1967 to 2007, and “Patti Smith: Camera Solo,” an exhibition of her photographs that opened at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut in 2011. “Camera Solo” will be on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario through May 19.

“I’ve always loved drawing,” Smith told me. “I’ve always felt connected to the idea of the written word and with the act of writing. When I was young, I wanted to be an illustrator because I didn’t really know what fine art was, but when I was 12 years old my father took me to the Philadelphia Museum and I saw a show of the work of John Singer Sargent. As a young person I fell completely in love with Picasso—I was just in Madrid, and I went to see Guernica, and especially the drawings he did as studies for it. Drawings are intimate and they have a close relationship with the written word—you can do both with a pencil. Sometimes I find myself so involved in the writing of a poem that it actually ends up becoming a drawing as well.”

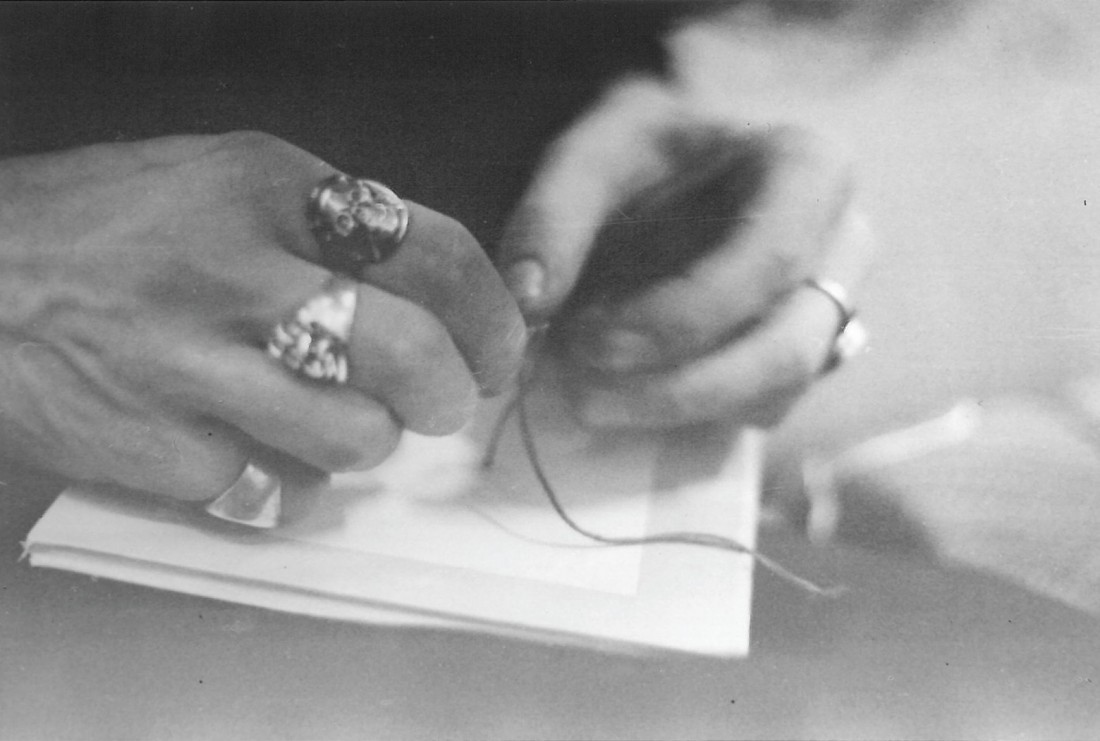

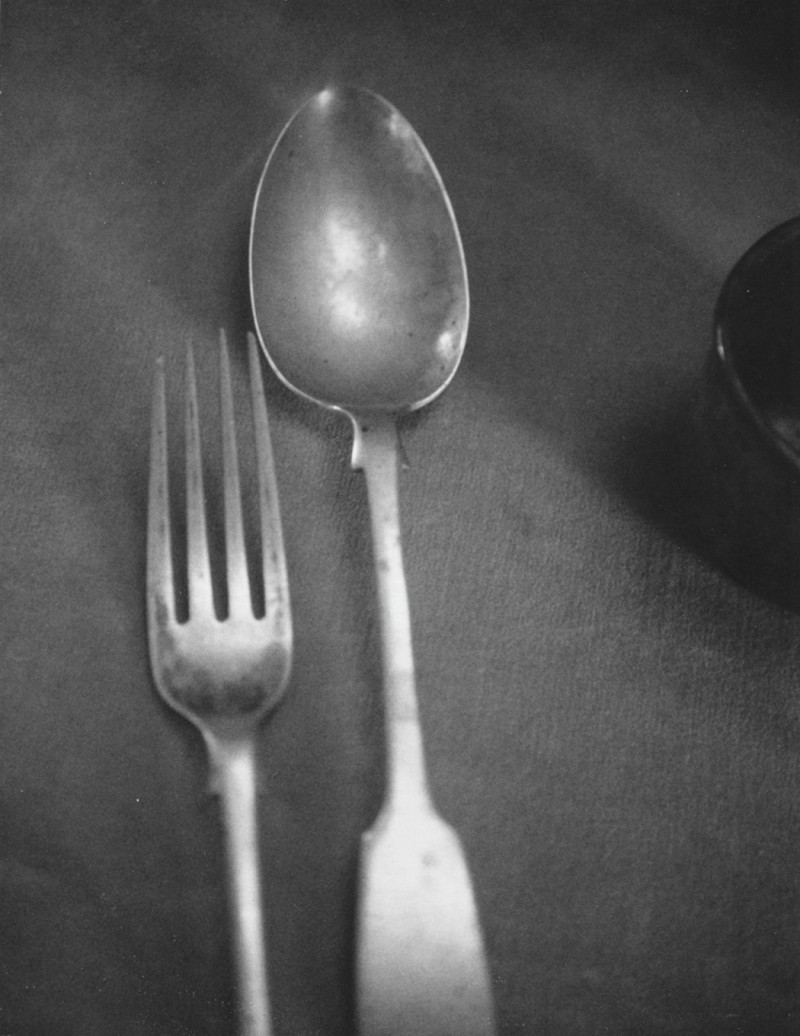

Patti Smith, Arthur Rimbaud’s Utensils, Musée Rimbaud, Charleville, 2005, Gelatin silver print, edition of 10, 10 x 8 in., 25.4 x 20.32 cm.

Smith’s drawings are both fierce and incredibly intimate and often, at least in part, consist of frantically improvised text. In the early figurative drawing, Self Portrait, 1969, which shows the strong influence of the Willem deKooning Woman series of the 1950s, Smith’s smeared head and face and truncated torso look like they are in furious motion, a black cloud of words rising like smoke from her head. The hand-drawn cover for her 1997 album Peace and Noise has text pulsing and swirling in what looks like either the petals of a flower or a map of flowing rivers. The drawing does not itself form a full, coherent text, but is rather an accumulation of words connected instant by instant and in various directions; here, the words themselves are indistinguishable from the marks, and seem the graphic equivalent of her well known vocal improvisations. Unlike Cy Twombly—whose work Smith admires but did not know until later—where the focus is mostly on the act and form of mark making itself, for Smith the verbal and the visual are completely intertwined. Other drawings are more wispy and lyrical. In Orchid, 1998, for instance, both the lines and the elegantly drawn cursive writing move in circles, form small, clustered islands, rise and curve and open. When she wants, Smith can draw in finely rendered script, and she told me that when she was young she loved copying things like the Declaration of Independence. In an untitled work from 2006, the lines, pale and occasionally smudged with pink and lavender, drift shimmering across the page as though over the surface of water. At one point there is a form that appears to be a hand holding pencil to the paper, which suggests that these drawings are as invested in their moment of creation as a saxophone solo by John Coltrane.

“I’m not a natural draughtsman,” Smith acknowledged. “I’m not like some people, who can draw anything. I never developed those skills. When I was 19 I leaped forward immediately—I was into Picasso, Kandinsky, deKooning, Pollock; the abstract expressionists have always been important to me. I tend to work in spurts. I can work on a drawing for months, and in order to do that, I need to be able to concentrate. The difficulty with being a performer is that I feel split down the middle: I’ve always preferred a solitary life, but being a performer is completely public, and it requires one to be completely present—when you’re performing, there’s no time to let the mind wander.”

Patti Smith, Virginia Woolf’s Bed I, Monk’s House, 2003, Gelatin silver print, edition of 10, 10 x 8 in., 25.4 x 20.32 cm.

“The Polaroids have been a blessing,” she continued, speaking of the black and white Polaroid photographs she takes with vintage Land 100 and Land 50 cameras and then has scanned and printed in editions, which is what will be on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario. “When you’re on tour, you can be in 30 different cities in 40 days, and I can go out and take a couple of photographs in every city. I’ve always loved photography. I remember when I was a child in the 1950s I would see Irving Penn photographs in Harper’s and I knew they were different from the photographs in the Sears Catalogue, and later I went to the library and saw photographs by 19th-century photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron. I’m not technically very good, and anyway these days anyone with a cell phone can take a decent photograph. I wanted to take photographs that I can take, and what I can offer is my sensibility and also the access I have. One of the most recent photographs I took was of Sylvia Plath’s grave in West Yorkshire—most people don’t travel as much as I do and so would never have the chance to see it.”

Smith has always been a romantic, a lover of poets, artists and musicians, and her work as a singer and songwriter, poet and visual artist is full of elegies, invocations and allusions to her heroes. The lovely Virginia Woolf’s Bed II, Monk’s House_, 2003, is, for instance, a picture of Woolf’s austere bed, cross stitched into the centre of the stark, white bedsheet, shot at a low angle with swarming shadows and a flash of light in the upper left-hand corner. Virginia Woolf’s Cane, 2011, on the other hand, is simply a picture of Woolf’s old, wooden cane, shot in direct light from above. Grave, Amedeo Modigliani and Jeanne Hébuterne, Père Lachaise, Paris, 2010, is a shot of the tormented artist and his equally tormented—and pregnant—lover’s grave, a long-stemmed white rose carefully set on top of it. Then there is Headstone for William Blake, Bunhill Fields, London, 2006, and Roberto Bolaño’s Chair 2, 2010, and Frida Kahlo’s Bed, Casa Azul, Coyoacán, 2012, shot with overlapping shadows, a skeleton set behind the bed. These photographs, which are notably devoid of people (apart from occasional self-portraits and pictures of her children, Smith rarely photographs people), are what Smith calls “third-class relics”; they are the places great artists have been, the things they have lived with, their final resting places. The sense is that by contemplating them we can absorb their presence.

Patti Smith, Robert’s Slippers, 2002, Gelatin, edition 5/10, 10 x 8 in., 25.4 x 20.32 cm.

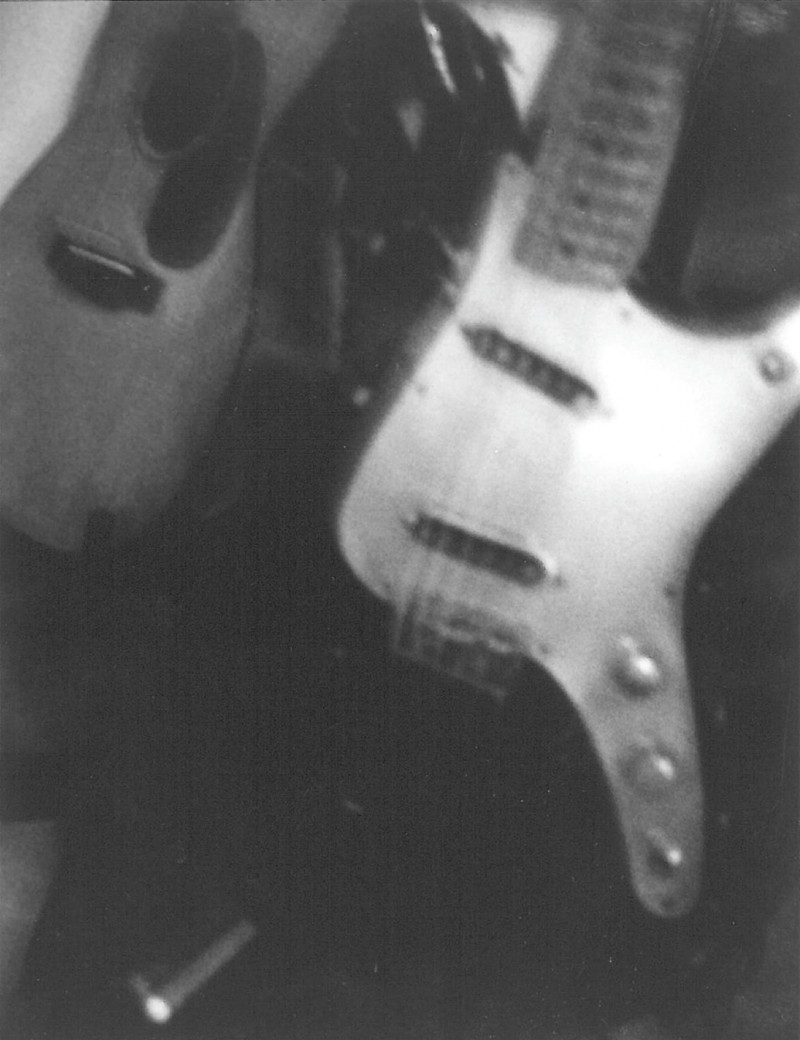

“A lot of people might think I’m morbid,” Smith admitted. “But that’s really not the case. I don’t think of these things and people as part of my past; they are part of my working life. I don’t think of Robert Mapplethorpe or my husband as part of my past, and while I never knew Rimbaud or Blake or Bolaño, they are always with me, and they have made my life more inspiring.” Not all of Smith’s photographs are of relics of the great artistic visionaries of the past; some are more private and introspective. In Self-Portrait, NYC, 2003, for instance, Smith’s head is tilted back against the wall, her face half in shadow, half in stark white light. Jesse with Flower, 2003, has her son’s extended hand holding a small, shriveled sunflower; Fender Duo-Sonic, NYC, 2009, is a blurry snapshot of Smith’s electric guitar, which she bought on time on the Upper West Side in the 1970s; and My Father’s Cup, 2004, is a simple still life of her father’s engraved coffee cup set on a shelf.

Smith has, from the beginning, had a powerful and ambivalent relationship to the spiritual traditions. This should come as no surprise: her mother was a failed Jehovah’s Witness (she was never able to give up smoking) and her first book was the Bible, and to this day she seems to have the prophets and the gospels at her fingertips. Her two favourite poets, William Blake and Arthur Rimbaud, are both arguably religious poets, though in a heretical mode: Marriage of Heaven and Hell and A Season in Hell are both steeped in a visionary tradition that descends from The Book of Job and The Book of the Prophet Isaiah. And while early Smith songs are sometimes aggressively iconoclastic—the famous refrain in the tellingly titled “Gloria (In Excelsis Deo)” goes “Jesus died for somebody’s sins/but not mine”—her subsequent work is increasingly saturated with religious, and specifically Christian, allusions. Think, for instance, of “Ghost Dance” from Easter (“Here we are, Father, Lord, Holy Ghost/Bread of your bread ghost of your host/We are the tears that fall from your eyes/Word of your word cry of your cry/We shall live again we shall live again”) or the same album’s title song (“I am the spring the holy ground/I am the seed of mystery”) or more recently in poems like “Eve of All Saints in Auguries of Innocence (“My dove, your name is water in my hand/I will offer it with salt and bread…) And Smith’s photographs reflect her enduring fascination with religion. Cross with Mirror, 2003, is a picture of an old stone cross set beneath a mirror, the cross’s reflection receding back into the mirror’s darkness. Ghent Altarpiece (The Backside of the Mystical Lamb), Ghent, Belgium, 2005, is an image, shot from an oblique angle, of Jan van Eyck’s masterpiece.

Art and religion, the pure life of the spirit and the transfiguring power of the imagination, confront one another in Smith’s stunning 10-minute song “Constantine’s Dream,” the high point of Banga. The song moves between, and ultimately beyond, Piero della Francesca’s resplendent The Dream of Constantine, 1452, part of the fresco cycle The Story of the True Cross in the Basilica of San Francesco in Arezzo, Italy, and the life of Saint Francis. “When Robert [Mapplethorpe] died, we had a mutual friend named Dimitry, and he sent me a postcard of the troubled King,” Smith recalled. “I ended up losing the postcard, but I spent years trying to find the painting in libraries—because of the armour on the guard, I assumed the painting was Spanish, so I was looking through books of Spanish art and at one point I even announced that I would search for the painting in every museum in Spain. Then I was in Arezzo on tour and I had this incredible apocalyptic dream of St. Francis receiving the stigmata. I couldn’t shake the dream, so I went out onto the street and found myself in front of the Basilica of St. Francis. I went inside to say a prayer and, when I looked up, there it was—the painting I had been looking for.”

Patti Smith, Fender Duo-Sonic, NYC, 2009, Gelatin silver print, edition of 10, 10 x 8 in., 25.4 x 20.32 cm.

“Constantine’s Dream” opens with guitar and slow, heavy drums, but soon layers of other instruments join in to create a moody, swarming soundscape, Smith’s voice low and moaning. “In Arezzo, I dreamed a dream,” she sings, “of St. Francis who kneeled and prayed/For the birds and the beasts and all human kind/All through the night I felt drawn in by him/And I heard him call like a distant hymn.” The song, whose text Smith improvised, was originally meant to be an account of her dream of St. Francis, but halfway through the song, her voice increasingly urgent and incantatory, the theme suddenly shifts. “But I could not give myself to him,” she intones, “I felt another call from the basilica itself/The call of art—the call of man/And the beauty of the material drew me away/And I awoke, and beheld upon the wall/the dream of Constantine/The handiwork of Piero della Francesca…” For Smith, St. Francis, friend of birds and wolves, a saint whose spirit had achieved a serene relationship with the natural world, is a model of how we, in our era of climate change and mass extinction, should aspire to relate to the world; but St. Francis was not an artist, did not transform the material of the world into something beautiful. “At that point in the song, I encountered my dilemma about art,” Smith said. “I don’t think we should have an imprint on the earth at this point, but art is really about making an imprint. I was brought up as a Jehovah’s Witness, which is a very austere religion. But when I saw art the first time, I knew that was what I wanted. I can’t imagine a world without art, no matter how perfect it is.”

“Still, I think prayer is the most important thing,” Smith reflected. “But it’s not always obvious what a prayer is—some prayers are asking for things, others are a form of praise. Think of Psalms. There’s an aspect of prayer in all of the work that I do. In improvisation, you try to find a deeper form of concentration, you try to find the deepest and purest part of you and draw it up and send it out to someone, whether it’s an ancestor or an archangel. You want it to come from a place that wakens God or the dead, and if you’re doing that then you know you’re doing something worthwhile. You can see that in a John Coltrane solo when he goes out to talk to God for 10 minutes and then comes back or in Rilke’s Duino Elegies. They are trying to find stepping stones to perfection.” Whether moving fluidly between a poem and drawing and back again, or taking a Polaroid of a fork and spoon Rimbaud once ate with, or launching full force into her ecstatic love song “Dancing Barefoot” on stage at the Kanata Centre in Ottawa nearly 20 years after her lover and husband died, Patti Smith’s art is powerful because of its incredible lack of self-consciousness, because it has a strange and furious kind of innocence and, most importantly, because it so obviously comes from a pure, deep place. She is, as the song goes, a benediction.