“Pattern Theory”

Pattern theory, which seems to have been engendered by Brown University mathematician Ulf Grenander in 1972, is as complex as it is absorbing, and if you don’t think so, go on Google and check it out. The simplest discussion of it—on Wikipedia—locates it as a “mathematical formulism to describe knowledge of the world as patterns”—which means it differs interestingly and profoundly from structuralism, with which most of us are more familiar. Pattern theory, intones Wikipedia, proceeds by prescribing a precise vocabulary with which to “articulate and recast the pattern concepts in precise language.” How appealing all that precision is!

An exhibition titled “Pattern Theory” opened last November at Toronto’s new MKG127 Gallery (MK for director Michael Klein, G for Gallery and 127 for the gallery’s address on Toronto’s Ossington Avenue). It was made up of the work of eight artists: Adam David Brown, Kristina Lahde, An Te Liu, Ken Nicol and Joy Walker of Toronto, New York-based artist Tom Koken, Hamilton-based artist Liss Platt, and Instant Coffee (counting the Toronto/Vancouver collective, Instant Coffee, as one artist).

Installation view, MKG127, Toronto, 2007. Images courtesy MKG127, Toronto.

The gallery’s press release put it all very simply: “In pattern theory, the belief is that the world is complex, and to understand it, or part of it, one needs realistic representations of knowledge about it.” Sounds about right.

It may be that I simply didn’t take the exhibition’s avowed aims quite seriously enough, of course, but for me there was an axis of inescapable buoyancy—almost levity—running through the show. Not that the clarifying and the quantifying of concepts need inevitably to be a sombre undertaking. It’s just that you don’t expect an exhibition called “Pattern Theory” to seem so charming.

It might have been better to have titled the exhibition “Pattern Practice” rather than “Pattern Theory.” Theorizing seems to call out for a little more discursiveness than most of these eight artists felt it necessary to offer. Most of what I saw was the result of an adherence to the realm of pattern-as-discourse, rather than any unlocking of such ideas.

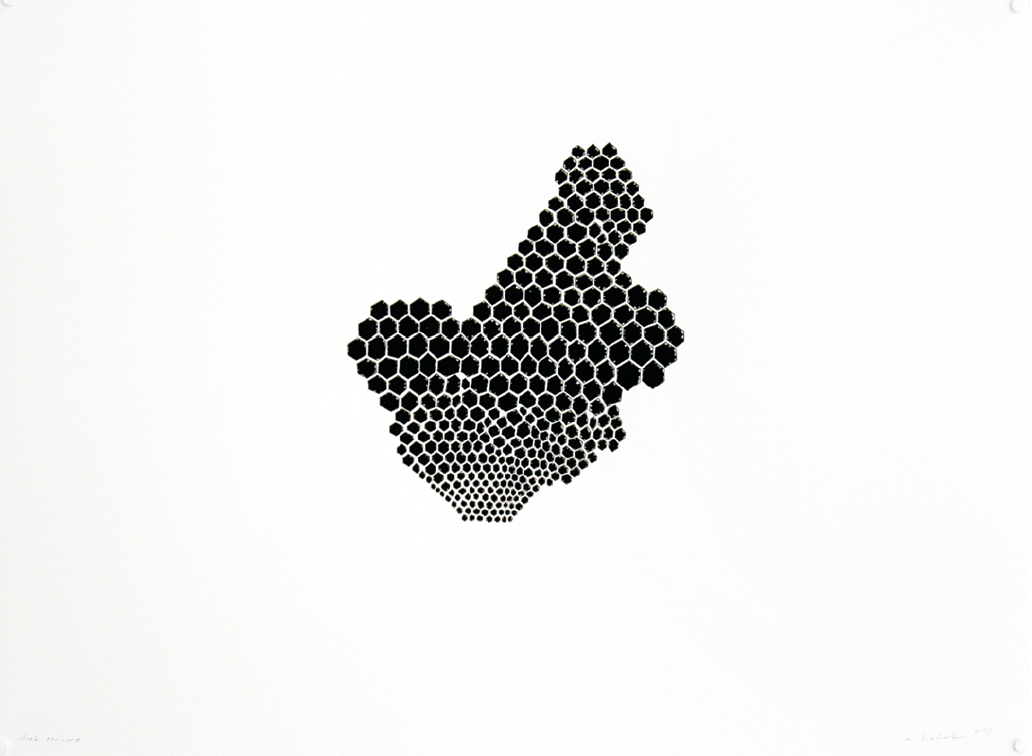

Kristiina Lahde, Dark Corners, 2007, ink on paper, 23 x 30”.

Take Instant Coffee’s construction, Platforms, positioned forthrightly on the floor, right in the middle of the exhibition. Platforms is a rearrangeable stack of pallet-like, bed-esque foam slabs, each with its own set of castors and each fitted with pseudo-craftsy, macrame-like, acrylic knitted blankets. You could call this stack of retro-fragrant platforms modular if that didn’t seem, in itself, so insipidly retro. Plentifully patterned—though in a wildly irregular, ad hoc way—the platforms of Platforms seemed too busy with both the mockery of, and the adhesion to, concepts of shelter and coziness than to any commitment or adhesion to the idea of pattern theory—except to suggest that pattern is anywhere you lay your theory-weary head.

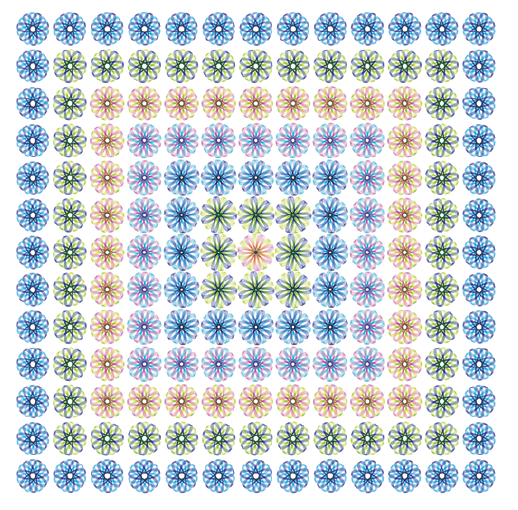

Liss Platt is to graphic art what Instant Coffee is to nostalgia-tinctured home furnishings. Her relentless employment of the Spirograph (you recall that insidious geometric drawing toy introduced by Kenner to North American kiddos back in 1966?), by which she offered some of the apparently infinite number of Spiro variations and combinations as ink-jet prints, resulted in aggregate pictures—row upon row of regular, if gnarled, graphic glitches in those unpalatably thin ’60s toy colours: weak acid greens, chemical pinks, listless blues, Thrills purple—well, you remember. Arranged in rows (disc 60, hole 7), Platt’s mechanical Spirograph blooms looked like a code or the phonemes from some needlessly ornate language.

Liss Platt, Untitled (disk 60, holes 3 to 10), 2007, ink jet print mounted on dibond, 27 x 27”, edition of 3.

Like Platt’s Spirographs and Instant Coffee’s Platforms, Ken Nicol’s Typer Grids were pictures made by employing the typewriter’s clunky ease with repetition to create graphic patterns that tended towards the accumulative if not the strictly systematic. The work seemed to rescind pattern theory in favour of a kind of primitive systematic art—formulating patterns that lie, like Pratt’s Spirograph drawings, somewhere between structure and utterance. Macrame, Spirographs, typewriters—how ’60s it all seemed!

Tom Koken’s tiny all-over oils on paper were visually mellifluous— though, for me, too reminiscent of pattern-devoted painters (like Joyce Kozloff) of the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s. Kristina Lahde’s one contribution to the exhibition was an invigorating little ink drawing called Dark Corners—a kind of matrix of hexagonal, beehive-like patterning—that looked as if she’d cut out a swatch of beehive-printed cloth and then drawn it in perspective: a colony of close-packed nascelles.

An Te Liu, Pattern Language: Levittown (brown/ seafoam), 2007, hand-printed silkscreen on paper, edition of 30 rolls, each roll 30” x 16’.

For me, the freshest and most provocative works in the show were by Joy Walker and An Te Liu. Joy Walker’s taut, tense, geometrically precise, exhaustingly laboured graphic structures presented as silkscreen prints were grouped in sets of parallel lines arranged into some quite monumental and architectural shapes—arch-like structures, steles, portals, folds that erect three-dimensional places on two-dimensional fields. I loved the way Walker’s line continually created fictively enterable spaces, graphic havens.

An Te Liu, who trained as an architect and works as an artist (he has the Canada Council Berlin studio this year), turned in “Pattern Theory’s” wittiest work. His Pattern Language—the title is a nod to architect Christopher Alexander’s famous book, A Pattern Language, 1977—is an encyclopaedic work that attempts a systematic examination of what makes buildings, streets and communities work. An Te Liu takes an aerial view of the Long Island proto-suburb, Levittown (1947–51), cuts and reverses the photo into symmetrically ordered patterns and, in the form of hand-printed silkscreens on paper (in “brown/seafoam”), offers it all up again as wallpaper. The meaning of these overly rhythmic houses potentially pasted up inside other houses is dizzying, both optically, historically and metaphysically. ■

“Pattern Theory” was exhibited at MKG127 in Toronto from November 24 to December 22, 2007.

Gary Michael Dault is a critic, poet and painter who lives in Toronto.