Patrick Howlett

In Working Space (Harvard University Press, 1986), Frank Stella’s 1983–84 Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, Stella urgently notes that the creation of “pictorial space…capable of dissolving its own perimeter and surface plane is the burden that modern painting was born with.” In his recent exhibition at Susan Hobbs Gallery, Patrick Howlett consistently played with and against this burden, bringing attention to the surfaces of his abstract, pictorially liminal canvases and then complicating them in subtle ways. Applying media such as pencil crayon and shellac or charcoal and watercolour to the raw absorbency of canvas and linen, and affixing geometric shards of canvas or wood to their surfaces, Howlett could show his surface plane as simultaneously present and withdrawn or cancelled, pushed into the unmeasured space beyond their material fact. Silverpoint on gessoed and painted wood panel was another unlikely combination that drew the flat, slightly syrupy and glossy white surface of suppression, 2010–2012, into a kind of ghostly cross-hatching, a geometrically inclined place of absence.

“Patrick Howlett: How Hummingbirds Choose Flowers,” installation view, Susan Hobbs Gallery, Toronto. Images courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photography: Toni Hafkenschied.

Howlett also complicates the perimeters of his paintings, working them out onto their painted wooden frames where they undergo changes of inflection: hard or soft transformations of lines, planes and spaces—like inversion, extension or dissolution in music. Some of the razor-thin black lines that issue out onto the frame of superadded, 2010—a delicate watercolour on paper work—are so clean and incisive that they appear to be frame joinery. But this effect is less trompe l’oeil than the visual consequences of Howlett’s methods of transforming his works (in this case, the addition of a frame two years on), allowing his images the consequences of earlier decisions, instituting change with the passage of time. By integrating work from earlier phases of his oeuvre into his current exhibition, Howlett worked against the unspoken, commercially pressured principle that a solo exhibition should be a snapshot of an artist’s newest production, instead giving us something more elastic and ontologically playful—under less of the moment’s pressure for the novelty of the new.

Some of Howlett’s forms and techniques are recognizably retrograde. Paul Klee is a major influence on Howlett, and it seems as though an important line in Klee’s 1920 Creative Credo, “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible,” serves to describe Howlett’s struggle with the internet-sourced origins of his images. He “renders the visible” by feeding a word or phrase—the work’s eventual title—into a Google image search. These renderings become image bases for each individual work. Howlett’s struggle is to transmute the rendered image into an almost altogether other thing; a labour in which the reflexively banal process of the internet search “rendering the visible” becomes the “making visible” of art. Klee, it should be added, is also an image source—or at least is one of the filters Howlett’s internet forms seem to work through or out towards.

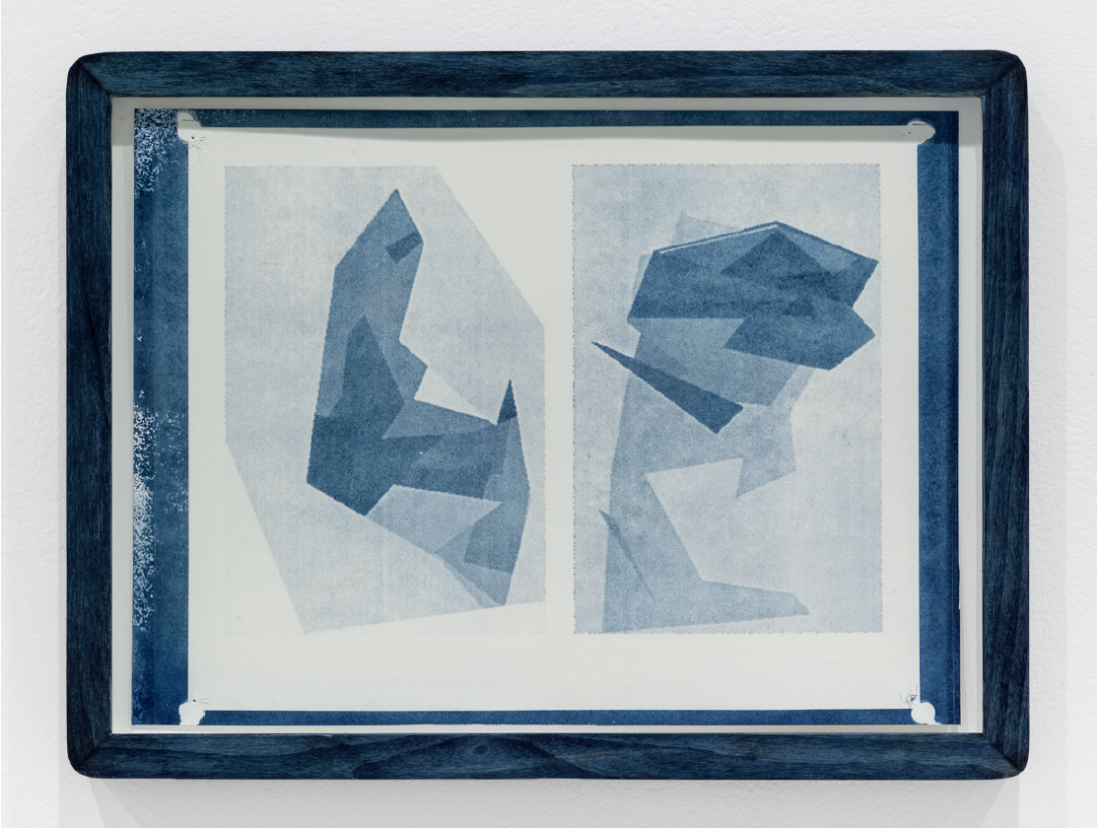

Patrick Howlett, chrysanthemums, 2008–12, cyanotype, 24.7 x 33 cm. Images courtesy Susan Hobbs Gallery. Photography: Toni Hafkenschied.

In arranging his works—some as small as 12 by 17 centimetres and others as large as 1.7 square metres—in a movement of clustered, almost swirling arrangements along the walls of Hobbs’s long thin rooms, Howlett showed a pre-modern concern with the architecture of the exhibition space. He produced an exhibition that read like both a mural and a book without being either. Book-like, the exhibition told a story contained within itself. But to really follow it, it was necessary to become what Stella called “a mobile viewer.” In Howlett’s case that meant moving between works, following the migration of forms and tactics, becoming a viewer who doesn’t just look but also remembers. Klee wrote, “Space implies the concept of time…It takes time for a dot to start moving and become a line, or for a line to shift its position so that a plane is formed. The same is true of a plane that moves and this defines a space. And the work of art—that is not all born in one moment, either. It has to be constructed bit by bit, just like a house.”

Howlett, however, deconstructs his images at the same time as he constructs his works. Untitled, 2009, placed early in the exhibition’s sequence, was an extreme example, a work that had once been complete but was, in later years, sanded back so that the original image was obscured. On this eroded base Howlett overlaid a small strip of wood like a three-dimensional Barnett Newman “zip,” painted white—the work’s original under layer now visible in places. Overall, Howlett’s drama plays out amidst the specific labours of coming into and going out of being.

Beyond the migrations and transformations of forms in his works, it was often impossible to tell which individual work belonged to which media. chrysanthemums, 2008–12, a cyanotype photo in a cyanotype-dyed frame, seemed certain to be a watercolour and conversely, cut out, a single name applied to two separate egg-tempera works on tape mounted on paper, appeared to belong to the category of printmaking. In many ways the exhibition could be construed as a quiet and intense demonstration of the unfixed nature of identity. ❚

“How Hummingbirds Choose Flowers” was exhibited at Susan Hobbs Gallery in Toronto from December 15, 2012 to February 2, 2013.

E C Woodley is a curator, composer, critic and artist.