“Pandora’s Box”

A slave sucks the penis of her hanged master, girls frolic naked in a playground, portraits are collaged from fragments of porno magazines, and hookah pipe hoses snake into a woman’s various orifices. This is not your mother’s feminist art.

“Pandora’s Box” is an ambitious group show installed in the Dunlop Art Gallery’s modest space within the Regina Public Library. The daring exhibition’s profusion of bare and often disturbing bodies led the management to black out the gallery’s large windows and door. Those who dare breech the barrier are rewarded with a refreshment of feminist art. Curator Amanda Cachia has assembled dozens of pictures and one video from artists, mostly in their 30s, of many nations and ethnicities: Laylah Ali, Ghada Amer, Shary Boyle, Amy Cutler, Chitra Ganesh, Annie Pootoogook, Wangechi Mutu, Leesa Streifler, Kara Walker and Su-en Wong. While a few engage traditional “women’s issues,” most seem unbounded by feminism’s imagined restrictions.

Kara Walker, Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, 2004, 16mm fi lm and video transferred to DVD, black and white, silent; 8:49 min. Edition of 5. Courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

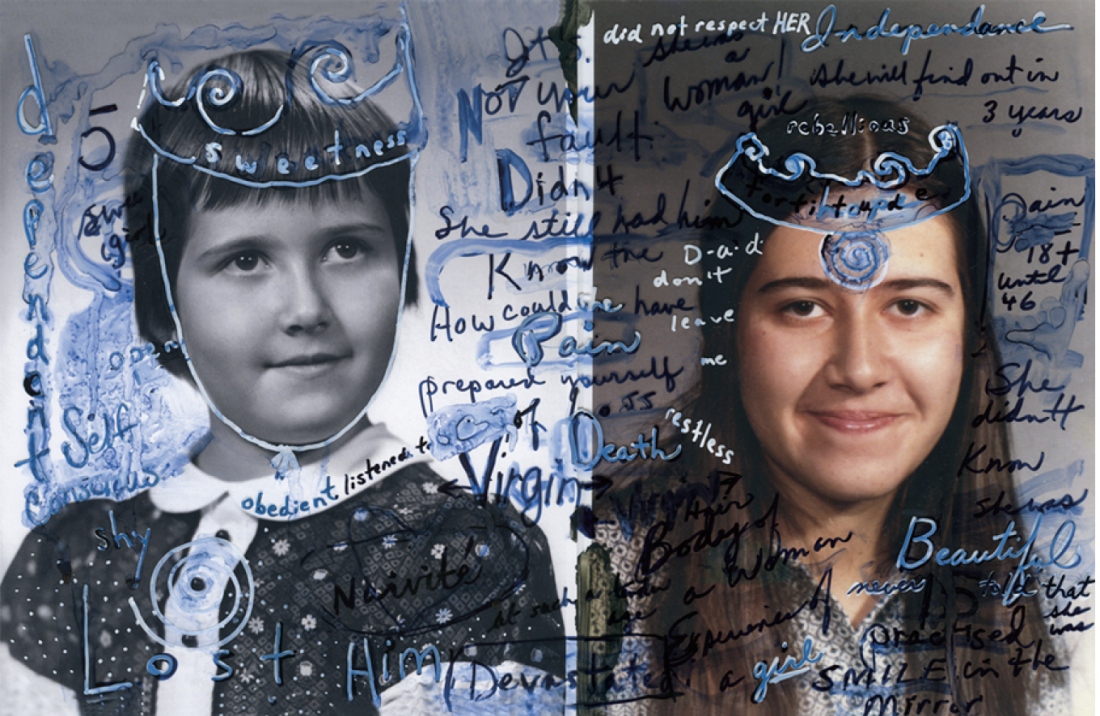

Leesa Streifler, the group’s senior artist, engages the familiar critique of gender socialization but suggests that this process is less imposition than dialogue. Her work consists of portrait studio photographs of herself at five and 15. Handwritten fragments, contemporary characterizations of her previous selves, swirl around and over her likenesses. The text on other portraits seems to record her mother and father arguing about the appropriate degrees of “discipline” and “control.” It may be that the artist’s voice is included in this exchange, or even that this is the artist’s internal dialogue concerning her own parenting. Her thoughts on correct child rearing and the exercise of power seem no more resolved that her parents’. The intertextual play, the endurance of the faces despite defacing attempts and Streifler’s acknowledgement of her complicity in this intergenerational project seem to favour a dialogic approach. Perhaps feminism has been the most self-conscious and anxious, but also the most thorough, complex and successful social movements in human history because its practitioners have chosen not only to answer for themselves, but also to their own mothers and children.

Annie Pootoogook’s drawings are close observations of everyday life. The style is simple but the insights are profound. While few share the specificity of her Inuit life, the broad strokes are universal. Three of her pictures depict domestic scenes. A young mother breastfeeds her child while her partner fiddles with a stereo. An older man watches his wife do the washing. A woman glances up from her work packing up the camp to see her husband relaxing with a cup of tea.

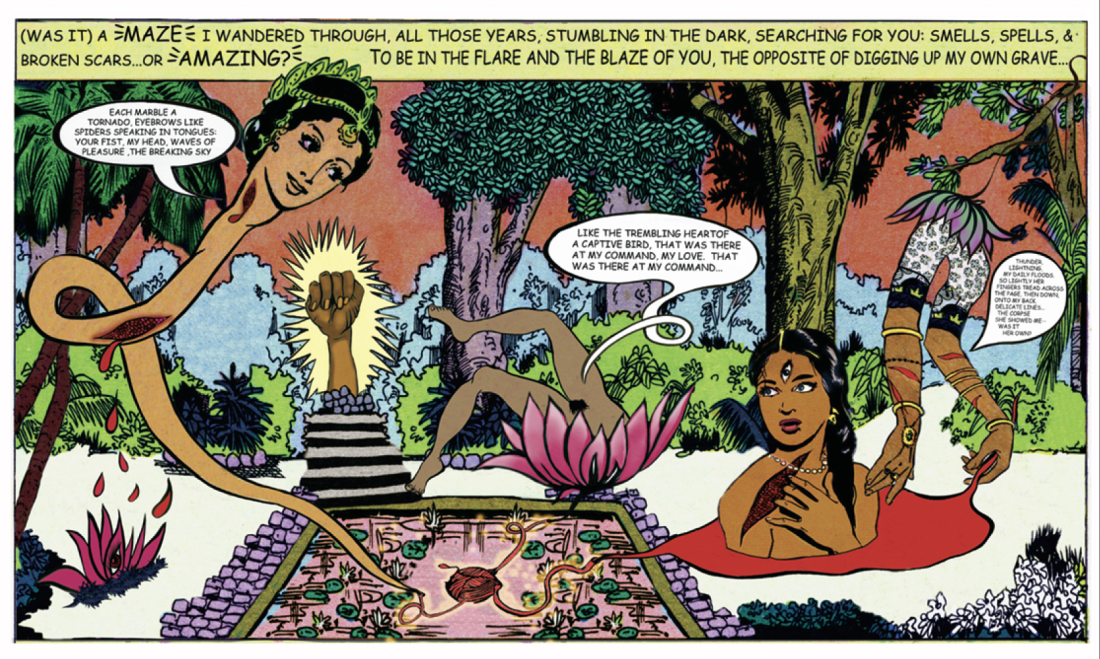

Chitra Ganesh, Dazzle, 2006, digital c-print, approx. 26 x 45”.

Pootoogook shows men who are selfish, lazy and indifferent and hints that this behaviour is generational. If we are in a liberal mood, we might project post-colonial explanations into these pencil crayon marks. But the look in the grandmother’s eyes as she gazes at her life partner suggests that she is looking for a little help, not a theory. Pootoogook doesn’t seem particularly interested in whether the unequal division of gender role labour is due to colonialism or traditional culture; she gently displays the inequity in the hopes that it raises consciousness and provokes individual change. Aboriginal teaching is by example and narrative rather than by explicit direction. The artist shows how things are and invites us to conclude that they should be otherwise.

Wangechi Mutu’s grotesque collages of women’s faces from fashion and pornographic magazines is a familiar indictment of the objectification of female bodies made stranger by the inclusion of ethnographic sources. Mutu’s mutilations recall the 18th- and 19th-century cataloguing of racial types that included the examination of genitalia around the world. Her use of clippings of animal parts indicts the association of females with nature and beasts. A less rote reading might see these monstrous faces as expressions of what identity feels like from the inside: multiple selves, made up of numerous aspects both received and innate, cultured and animal, static and revised.

Leesa Streifl er, Parenting Revisited: portrait at 5 and 15 years, 2008, c-print, 20 x 25 cm. Collection of the artist.

Few of the remaining works in “Pandora’s Box” are so overt in their engagement of women’s issues. Most are subjective and idiosyncratic. Shary Boyle’s surreal fairy tales combine innocence with dark ritual, and Amy Cutler’s woman attracting a flock of swallows with her birdhouse head are open to numerous associations and interpretations. Rarely do the younger artists reduce their images to illustrations of theory. Most are unresolved and cryptic expressions. They embody rather than attempt to explain and resolve conflicted states.

Kara Walker’s film Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, 2004, is a short, black and white silent movie that combines shadowbox puppet theatre with stop-action animation. The story seems a revenge fantasy in which a slave girl lynches her master/lover. The narrative climaxes with the young woman sucking on the erect penis of the hanged man resulting in Jackson Pollock-esque spurts of paint. The dream-like film complicates the master/slave dichotomy and denies easy moral calculations when love and sex mix with race and power. Walker and the work of others in the show argue that feminist practices that focus on the social and do not consider the uncontrollable personal territories of desire, contrariness and the carnival-esque will compose an incomplete picture of female experience.

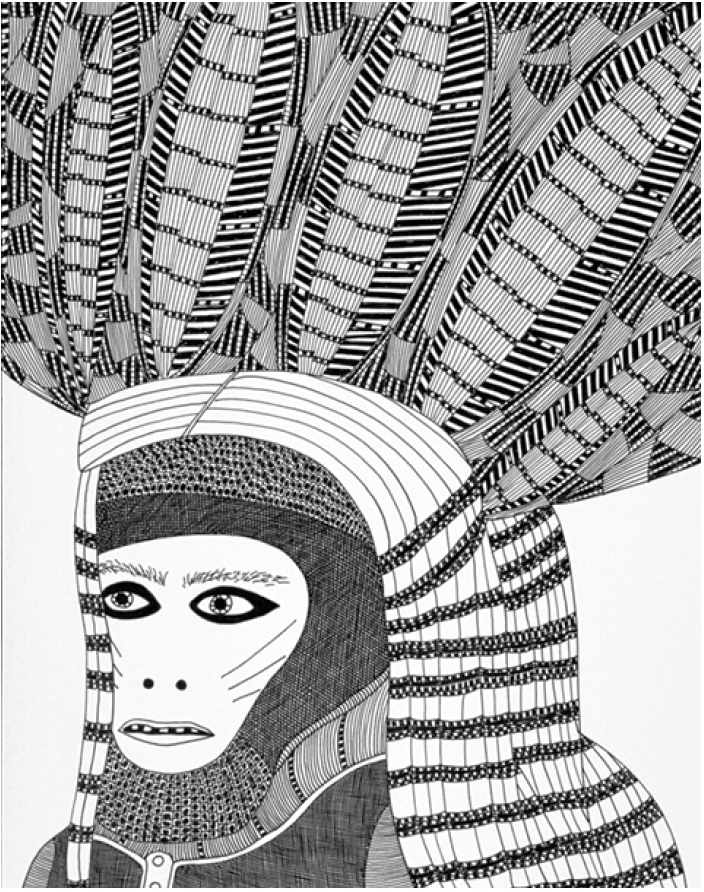

Laylah Ali, Untitled, 2005, ink and pencil on paper, 35 x 27.5 cm. Courtesy Gallery 303, New York.

Most of the works in “Pandora’s Box” subvert, pervert or at least reconsider childhood innocence. There are many naked girls here, naked and strange. Shary Boyle’s surreal, pre-pubescent girls are fabulations that cavort through unreal space. Hers is emergent but indecipherable and unruly unconscious content. Su-en Wong conflates her adult and childhood bodies, multiplies them and sets them loose in the playground. Her precocious clones reveal doings beyond adult surveillance. The child/adult blend suggests that subjective perceptions of childhood experience construct adult selves as richly as do more traceable social factors. Boyle adds the unconscious elements to the mix, suggesting that there are unresolvable sources of our selves beyond the discourse of reason.

In her excellent catalogue essay, Joan Borsa explains that many artists are uncomfortable with the term “feminism” because they have “a desire to set the terms of one’s own practice.” To some, feminist art is a time-bound category, a movement that began 40 years ago, flourished in the ’70s and ’80s, and then survived during the “backlash era” only in the academy as a pedagogic form. Contemporary artists are as sensitive to trends as academics. No one wants to be identified with yesterday’s fashion or theme, unless they can find a way to make it newly relevant. For her part, Borsa aligns these artists with third wave feminism: less collective, less political, more individualistic and subjective than the second wave. Most refuse the style of the older forms of feminism and feel no obligation to acknowledge its history, even while enjoying its benefits. Artists, like the rest of us in this amnesiac age, advance by limiting our knowledge of the past or by interpreting it to suit present desires. “Pandora’s Box” has us wonder what has been lost and gained in this dramatic shift in approaches to women’s experience and expression. ■

“Pandora’s Box” was exhibited at the Dunlop Art Gallery in Regina from May 16 to July 20, 2008.

David Garneau is a painter, writer, curator and Associate Professor of Visual Arts at the University of Regina.