Painting Paintings

Words freed Eric Fischl to make images. In the process of writing his celebrated memoir, Bad Boy: My Life On and Off the Canvas in 2013, the American painter came to recognize what the art world had become. Finding his voice in the writing cleared the space for him to make paintings about the transformation he had witnessed: the art world was now the art market.

Acknowledging what he calls his “profound level of disappointment” led to the Art Fair paintings, a subject he thoroughly investigated in his recent exhibition at the Skarstedt Gallery in New York. The paintings list a collection of qualities unique to the social and economic ecosystem of the current art world. “The beauty of an art fair is that it is like a circus,” Fischl says, “it is egregious and bizarre and carnivalesque and tragic.” He had never been to an art fair. “I went in as a spy. Nobody knew what I was looking at when I pointed my camera at things, so I was left alone. After the first show of Art Fair paintings people started to get what I was doing and I would find them actually manoeuvring into my camera. They wanted to be a part of this thing.”

One of the advantages in making paintings about the art world is that, willy-nilly, you are making paintings about art. It becomes a meta-project. Since the early ’80s, Fischl has included art in his paintings, a practice that reached its zenith in “The Krefeld Project” in 2002. Fischl hired two actors to play out a sequence of domestic scenarios; the couple showed the focus of their art taste and the depth of their bank account in having works by Beckmann, Bruce Nauman, Andy Warhol and Gerhard Richter on the walls of their exquisite Mies van der Rohe house. The couple and their art collection were actors and props in a carefully staged pictorial drama.

Rift/Raft, 2016, oil on linen, 98 x 220 inches. All images courtesy the artist and Skarstedt, New York.

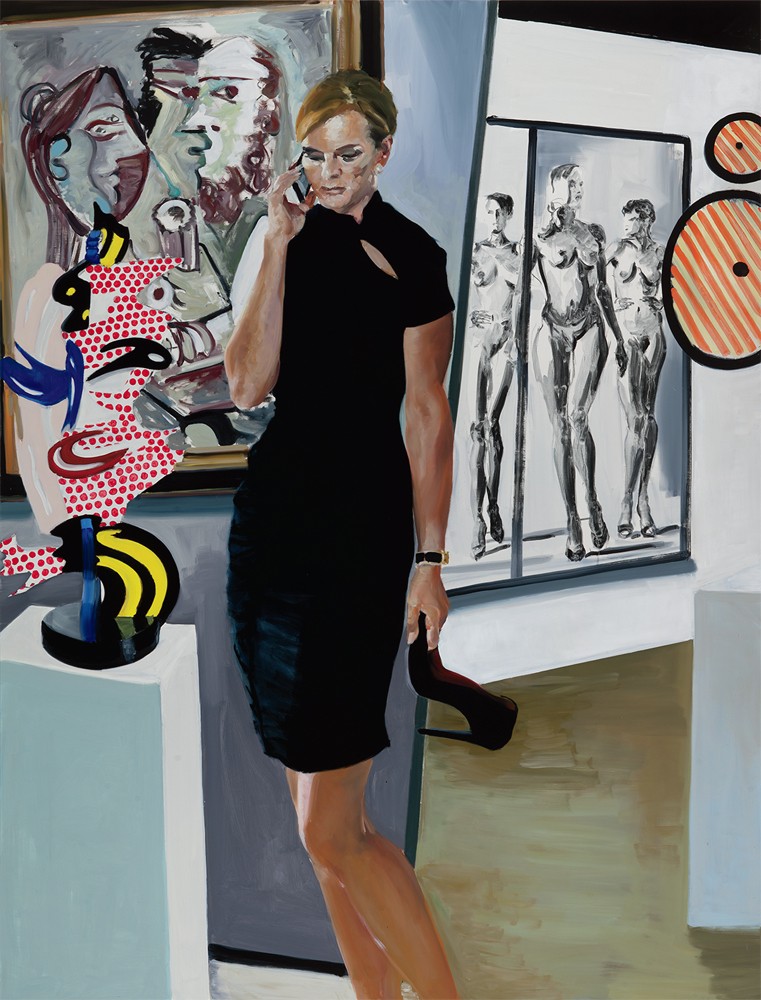

There is a connection to the way art is used in the “Rift Raft” paintings. Each includes specific works by recognizable, mostly living, artists: John De Andrea, Chuck Close, Carroll Dunham, Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein, Sarah Lucas, Helmut Newton, Pablo Picasso, Jack Pierson, Andy Warhol, Tom Wesselmann and Christopher Wool. The list, including painters, sculptors and photographers, is impressive and wide-ranging, but they are not all artists whose work Fischl necessarily admires. He appreciates the exuberance of Dunham’s overly sexualized female nudes—“they’re funny and energetic and naughty”—and dismisses Christopher Wool—“they are devoid of emotional content and are deeply cynical paintings about the emptiness of painting.” Fischl views Wool’s parody and Warhol’s ironic distance as signifiers of the decadence he feels is too much a part of the contemporary art world.

There is another kind of quotation operating in these paintings that is not as direct as reproducing actual paintings and sculpture. The painting from which the Skarstedt exhibition takes its name is doubly referenced; it recapitulates the drama of Theodore Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa, from 1818–19, and reprises and extends A Visit to / A visit from / The Island, one of Fischl’s own paintings from 1983. Both Rift Raft and The Island employ a two-part structure to depict a tragedy in the making. The more recent painting comments on the global refugee crisis and combines that dire situation with an art fair scene in which naked women and collectors are absorbed in their own hermetic world. Rift Raft presents a real-life theatre of disconnection. “I’m feeling something but I can’t connect to it and I can’t aid it in a way that is big enough for the disaster,” Fischl says, “and it leaves me with a pervasive feeling of hopelessness, as well as helplessness. It contrasts with this other reality that is incredibly privileged and as emptied of importance as the other one is overloaded with importance. And neither place is tolerable for exactly the opposite reasons.”

Her, 2016, oil on linen, 90 x 68 inches.

Fischl doesn’t hold himself outside the critique levelled at an art world dominated by the market. In The Disconnect, along with a Lichtenstein Brushstroke sculpture and a Haring Barking Dog, he includes his own 1987 painting called Girl With Doll. “I’m acknowledging that I’m a participant.”

A quality of despair sits on the surface of these paintings. But there is also the surface of the paintings themselves. The 10 works in “Rift Raft” end up being more about what painting contains than what it lacks. They are more about embodiment than lacuna. Look closely at the title painting; it is about our current history as much as Jacques-Louis David’s was about his; it composes itself through the architectonic memory of how Renaissance masters made paintings; and its varied and dense blacks are the most profound we have seen in American painting since Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell. In this body of work, surface delight rises above surface despair. Fischl’s rifts compose a raft on which painting, once again, can set sail. ❚

…to continue reading the issue, order a copy of Issue 139: Painting here, or SUBSCRIBE and receive a limited edition Border Crossings tote, screen-printed in the fall of 2016.