“Once Upon a Time…”

When the first words to greet us in a story are “Once upon a time …,” we tend to accept two principles: that something that once existed no longer does and that the territory we are about to enter resides more in the range of fable than fact. This is to say we understand such stories through a kind of shallow lament and a forgiveness for either the inflation or the lacunae that are the constituent parts of myth. Attentive to these qualities, the aptly named “Once Upon a Time … The Western: A new frontier in Art and Film” on exhibition at Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts reveals the American West cloaked in nostalgia that does not comfort as much as it chafes. Impressive in scale and breadth, in justice to a topic very much positioned on the notion of expanse, the exhibition revisits the West to examine the generally misrepresented and mal-aligned underbelly of the genre’s most prominent narratival tropes, such as progress (vs. displacement), cowboy (vs. “Indian”) and personal revenge (vs. cultural preservation).

Charles Schreyvogel, Breaking Through the Line, no date, oil on canvas, Tulsa, Oklahoma, Gilcrease Museum, gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation. Photo: Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma. Images courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal.

Acknowledging the poignant relationship between America and its cinema in imagining nationhood, with the Western genre being one of its main conduits, the exhibition uses motion picture film as its centre point, and gives careful examination to the manner in which film and fine art have contributed to building the American West into a legend of enduring stature. In doing so, it asks how a myth so foundational to the concept of nation can be positioned on elements as volatile as racism, sexism, violence and a sense of territorial entitlement. While the show’s title might suggest that this is indeed a time gone by, the cumulative effect of the exhibition reveals that the recurring tropes of the Western, positioned unfailingly around some sense of otherness or less-ness are ones that quite distressingly seem to underpin a precarious state of contemporary nationhood (one not necessarily limited to the US). In illustrating issues that speak to gender and racial inequality, we might safely assume—and indeed a catalogue will attest to the fact—that the majority of the works presented in the show are by white men, with works by minorities being very much the minority.

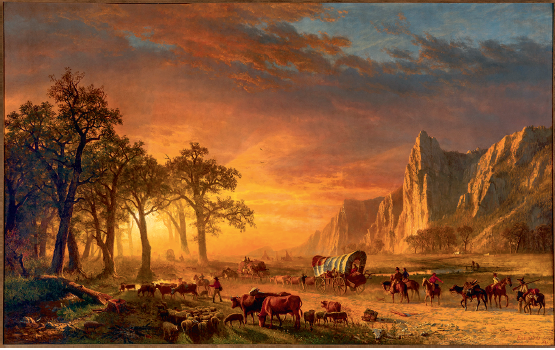

Albert Bierstadt, Emigrants Crossing the Plains, 1867, oil on canvas, Oklahoma City, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, gift of Jasper D Ackerman. Photo: MMFA, Christine Guest.

“Cumulative” is indeed an operative word for this exhibition, whose constituent parts (painting, photography, sculpture, film, ephemera) from periods spanning the 19th to the 21st centuries reveal fascinating linkages between art and film, and fiction’s appropriation of real lived experience. Although many of the Western’s themes show surprising resilience (to this day), the space in which they unfold is much changed. In the first gallery, we are reminded of the vastness of the 19th-century western landscape through paintings and photographs whose original intent was to translate the sublimity of the West into a seductive concept of “potential” that would encourage settlement. Landscape painters such as Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran and William Brymner depicted territories reigned over by moody or playful skies, and gave human staffage and enterprise diminutive scale. Photographers Carleton Watkins, Timothy O’Sullivan and Eadweard Muybridge likewise took advantage of the aesthetic of the sublime vista by exploiting the notion of nature untouched. Their compositional framing imposed on these settings a sense of ownership, thereby inserting the human. In the centre of this circular room is a large vitrine housing authentic items of Indigenous clothing; in the gallery’s physical arrangement, with “art” on the walls and “artifacts” encased in glass, there is an uncomfortable reminder of the tendency of Indigenous works to be thought of as the territory of anthropology museums, while Eurocentric attitudes deem art galleries a welcome home for “high art.”

The prominence of landscape in the myth of the West made it often the most compelling (or authentic) protagonist in Western cinema. Renowned filmmakers such as John Ford and Sergio Leone understood how landscape contributed to dramatic tension, as well as created an aesthetic arena for action. Praised as “masterful” by the likes of Orson Welles, Ford found inspiration in classic 19th-century and early 20th-century Western American painters, and, through careful study of their work, was able to elevate the genre to a more sophisticated rendering of character and plot that avoided stereotypes. Of particular influence was the painter Frederic Remington, whose style Ford attempted to emulate in colour and movement. Remington’s The Old Stage-Coach of the Plain, 1901, found near the entrance of the screening room dedicated to Ford’s work, is a striking example of the “Remington style.” This sparse composition, which favours mood over detail, depicts stage coach travel by night; a sense of foreboding is cultivated through the opposition of highlight and shadow and in the guarded gestures of the riders. In perhaps his most celebrated film, The Searchers, 1956, Ford achieved a similarly saturated mood by placing solitary figures in expanses of unadorned snowfields and desert landscapes. In a reverse gesture where film evokes painting, Sergio Leone arranged topography into patterns of dots and lines, which he then juxtaposed with textile motifs worn by the characters, making for an almost painterly effect.

Unknown Cheyenne artist, Vincent Price Ledger Book, p. 202, about 1875–1878, graphite and coloured pencil on paper. Courtesy Donald Ellis Gallery, New York.

While the films form the nucleus of “Once Upon a Time,” and the paintings and photographs present both atmospheric and narratival influence, revealing the potential true life of the “stock” character, the strongest pieces of the show— the ones that challenge the stereotypes of the Western myth most aggressively—can be found in the penultimate gallery. Here is Kent Monkman’s lavish Boudoir de Berdashe, 2007, a large tipi made from an ornate textile, in which you are invited to rest on Victorian furniture while watching a screening of a black and white silent film called Shooting Geronimo, starring Monkman’s alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle. On the wall next to this piece is the excellent oil on canvas, Soft Borders, 1997, by Mark Tansey, which, the artist states, is a “short history of the West from four different points of view.” Painted in a realist style, Tansey’s detailed rendering of canyon walls in a reddish hue gives the impression of a topographic map that pieces together four interrelated, yet distinctly arranged, scenes involving surveyors, tourists, a band of “American Indians” and what appears to be a toxic-waste-removal crew. A number of the figures are placed in impossible positions, often at odds with the laws of gravity— this and the apparent disconnect between the groups invite both the squint and the scan. A final work of note in this room, although all merit comment, are the soft sculptures by Gail Tremblay, made using Mi’kmaq traditional basketry techniques but employing less traditional materials. In And Then There is the Hollywood Indian Princess, 2002, and Indian Princess in a White Dress, 2006, Tremblay, rather than weaving with strips of ash wood, as is typical of the tradition, uses 16mm film in which a white hero falls in love with an Indian princess, generally played by a white actress.

Brian Jungen, The Prince, 2006, baseball gloves and dress form. Montreal, Claridge Collection. Photo: Denis Farley.

In some logical progression from the non-traditional use of film to film used to tell less traditional versions of classical tales, we find in the final gallery screenings of excerpts of contemporary Westerns, with the most famously unconventional among them being Quentin Tarantino’s Hateful Eight, 2015, and Django Unchained, 2012. As with most of Tarantino’s films (and not unlike classic Western tales), revenge is the major driver of plot and violence is the means to the ends. There is now another layer of violence embedded, postproduction, in these two films already excessive in bloodshed, in their both being distributed by the company owned by Harvey Weinstein and his brother. With a revelatory moment in American history currently unfolding in the contemporary Wild West of Hollywood, we are again reminded that “Once upon a time” does not necessarily occur “in a land far far away.” ❚

“Once Upon a Time … The Western: A new frontier in Art and Film” was exhibited at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts from October 14, 2017, to February 4, 2018.

Tracy Valcourt lives and writes in Montreal.