On Letting Go: How Art Institutions and Artists Are Correcting History

It is difficult to discuss the unprecedented upheaval of the past year without sounding clichéd. From the amplification of social justice movements to the devastating worldwide pandemic with near and far ramifications, including unimaginable death tolls from negligence as well as institutional and systemic inequities, the weight of what has been inherited will take us so long to work through that it seems impossible to even begin. But to suggest the work hasn’t already started would be false. So, with this in mind, I want to consider three events that took place since the world paused, pivoted and persevered. In the summer of 2020 the non-profit art centre Yale Union Contemporary, in Portland, Oregon, did something that no one would see coming: they let go. At the same time, Divya Mehra was about to open an exhibition with Regina’s MacKenzie Art Gallery in Saskatchewan, at the core of which was the repatriation of a cultural object that had been stolen more than a century prior, forcing the hand of the institution to let go. In the fall of the same year, the eminent conceptual artist Garry Neill Kennedy exhibited his private collection with Griffin Art Projects in North Vancouver. What was not immediately evident, however, was that Kennedy was also learning to let go.

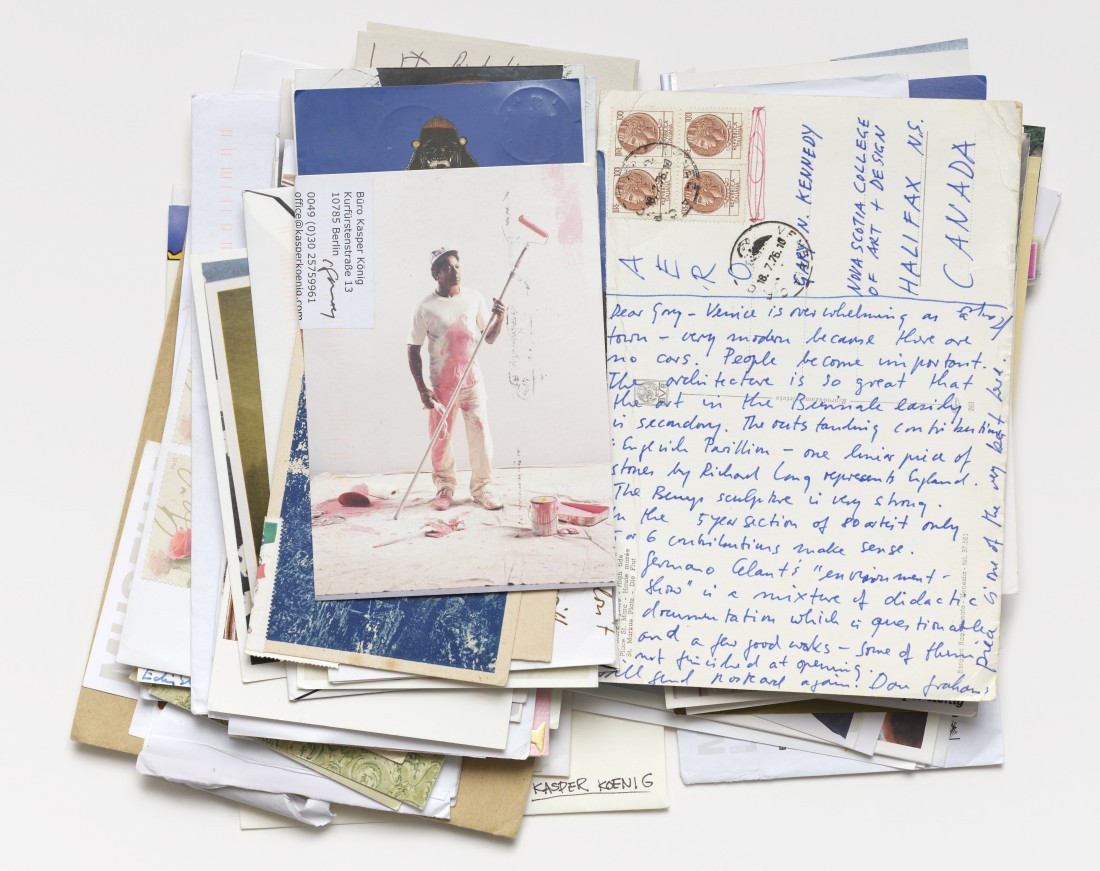

Kasper König, various postcards, drawings, printed matter, collection of Garry Neill Kennedy and Cathy Busby. Photo: Rachel Topham Photography. Courtesy Griffin Art Projects, Vancouver.

Yes, this is messy, but stay with me as I attempt to clarify these overlapping histories and how the (art)world played witness. Yale Union had a successful, decades-long history of producing contemporary art exhibitions and projects in a building built in 1908 on the border of the Buckman neighbourhood of southeast Portland. Having initially operated as a commercial laundry for 50 years before housing an automotive manufacturing facility until 2006 (at which point the Yale Union building was listed on the National Registry of Historic Places in recognition of the role it played in the women’s labour movement), the two-storey, 36,000-squarefoot space, built near an estuary, was unlike many non-profit art centres and yet shared with all of them the same history of operating on stolen land. As their website, which now functions as a complete archive of activities, notes, “Yale Union acknowledges that it occupies the traditional lands of the Multnomah, Chinook, Kathlamet, Clackamas, Tualatin Kalapuya, Molalla, and other Indigenous peoples.” Yale Union functioned as a publisher, an artist’s residency and a space for exhibits and events. In July of 2020 a transfer of the building and land was completed, allowing Yale Union Contemporary to dissolve and the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation to take ownership of the property. The final project organized by Yale Union—a solo exhibition by Kwakwaka’wakw artist Marianne Nicolson of the Musgamakw Dzawada’enuxw First Nations—is due to open as this magazine goes to print.

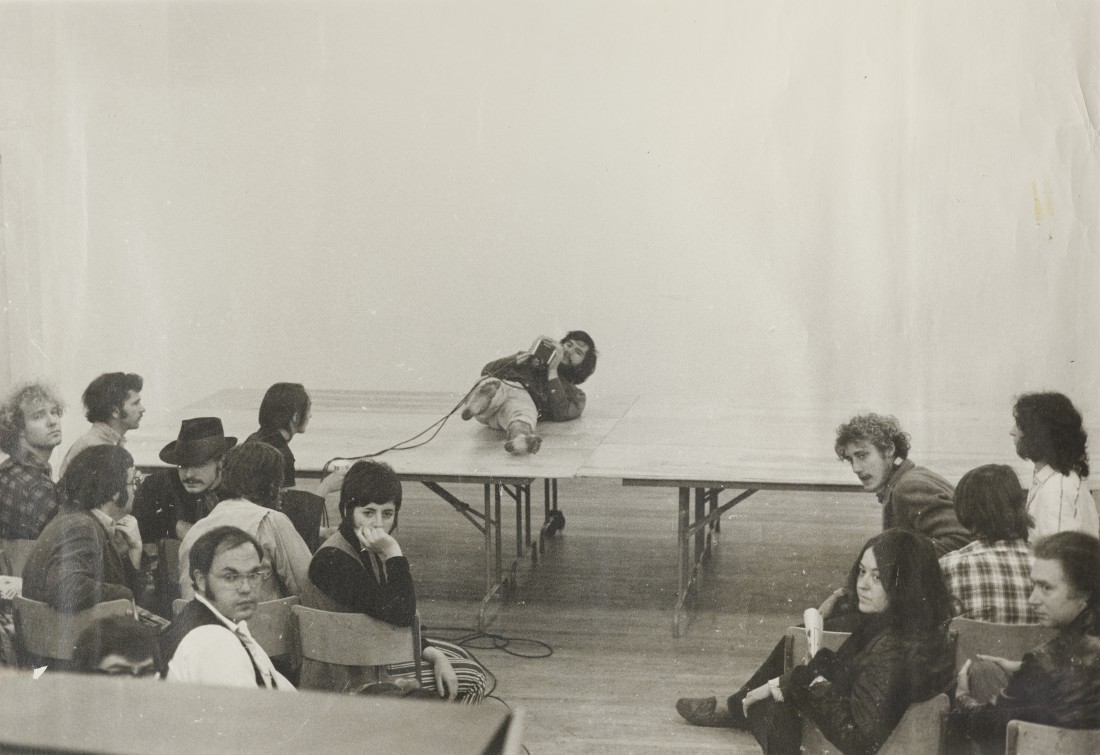

Dan Graham, Horizontal Roll, 1971, performance documentation, collection of Garry Neill Kennedy and Cathy Busby. Photo: Rachel Topham Photography. Courtesy Griffin Art Projects.

Upon being invited to present her touring work, consisting mainly of a 15-foot-square bouncy castle scale replica of the Taj Mahal that, when installed amidst the holdings or architecture of the host gallery, often critiques the homogeneity of collecting practices by institutions in the West, Divya Mehra found something surprising in the collection of the MacKenzie Art Gallery. The gallery’s namesake is Norman MacKenzie (1869–1936), a lawyer and avid art collector with a penchant for travel, and whose friend Edgar James Banks may have been the real-life inspiration behind the Indiana Jones character. Deep in the vault of the institution, Mehra came across a small carving that she could immediately tell was misidentified as the Hindu god Vishnu. This artwork was Indian in origin, and, after consultation by Dr Siddhartha V Shah, curator of South Asian Art at the Peabody Essex Museum, was properly identified, by her ladle and bowl of rice pudding, as the goddess of nourishment, Annapurna.

When Mehra alerted John G Hampton, then-director of programs and the curator of the project, to this misidentified deity, he asked her what she wanted to do and, without missing a beat, she offered, “Give it back.” In the seven decades of the MacKenzie Art Gallery, whose collection includes 5,000 objects spanning 5,000 years of art production, there has never been a deaccession … until now. The response by the institution was that something would have to be acquired to fill the gap, and in Mehra’s signature tongue-in-cheek style, a bag of sand à la Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom was proposed. Luckily Norman MacKenzie had kept detailed records of his travels, including anecdotes of hiring locals to steal objects of cultural and religious value and recording how he had come by this particular statue while travelling through Varanasi in the early 20th century. And ultimately, therefore, to where it could be returned.

…to continue reading the article by Kegan McFadden, order a copy of Issue #157 here, or Subscribe today.