On Kawara

“Consciousness. Meditation. Watcher on the Hills” at The Power Plant is a wonderful touring retrospective of three well-known On Kawara works: the date paintings; the telegrams; the million-years books. The “Today Series” of date paintings was begun in 1966. For all these years, Kawara has been painting the date on that day wherever he happens to be (he’s a world-travelled man). The day, month and year are abbreviated and formatted according to the norms of his location and are meticulously rendered by hand (drafting with only a ruler and a pencil) in freshly mixed paint—white sansserif lettering on a dark ground. If the painting is not completed by midnight, it is destroyed: more than 2000 have been made. One painting for each year of production— selected from those made on Sundays—is included in the large hall of The Power Plant, ranging in size but, for the most part, manageable to work with on a desktop.

The selection of “Sunday paintings” by Kawara and curator Jonathan Watkins is, I suppose, a bit tongue-in-cheek, and I use the phrase here to introduce the ideas of hobby and pastime: activities people generally do for leisure. Does the artist have nothing but to pass the time? Does anyone? I want to resist placing Kawara among the leisure class—clearly, his work is work, not hobby. But the ideas of passing time, of time passing, of moments filled with the activities of living are important in Kawara’s work, which is ultimately about Kawara’s experience of being alive.

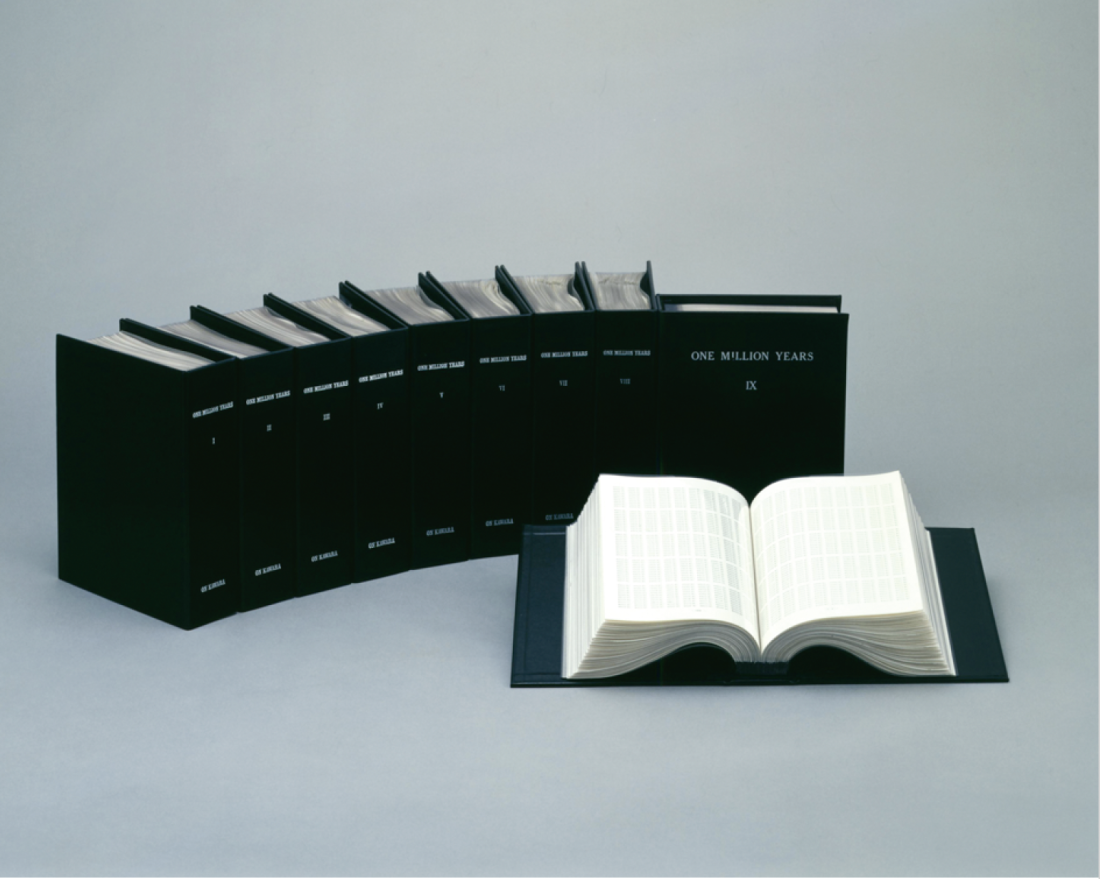

On Kawara, One Million Years (Past), 1970–71. Courtesy On and Hiroko Kawara and Power Plant, Toronto.

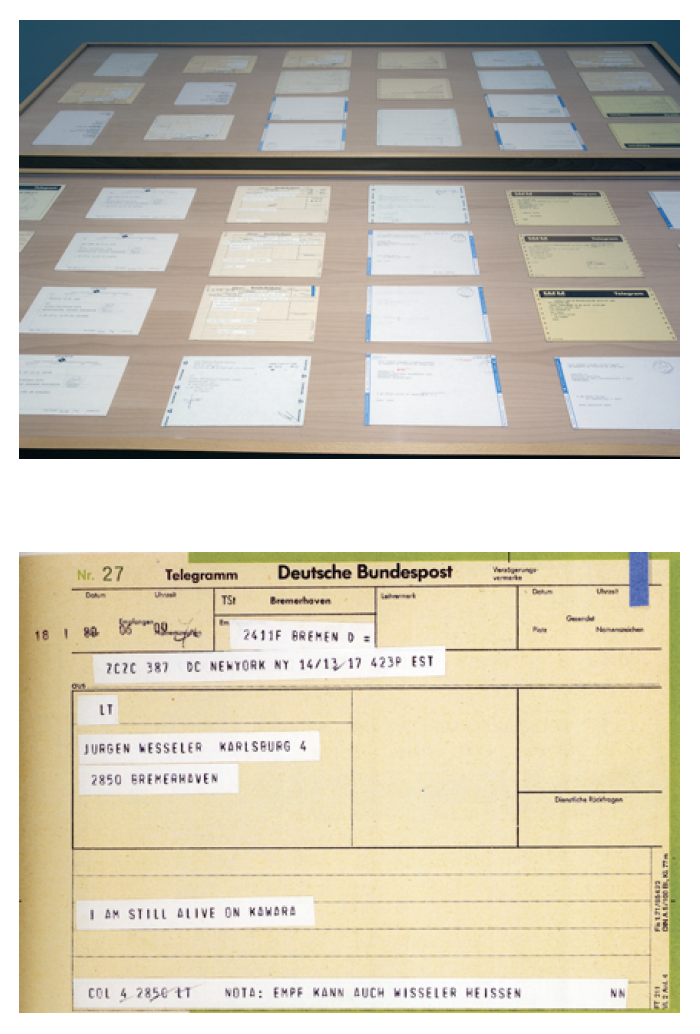

In a smaller adjacent gallery are selections from “I Am Still Alive,” in production since 1970. In seven, thigh-high, glass-topped tables rest 163 personal telegrams from Kawara to various friends, artists, art dealers and acquaintances, in private proclamation: I AM STILL ALIVE ON KAWARA. Just that. Whether it is true or not upon receipt (so far it has been), sending a telegram takes time. I wondered, while carefully reading individual telegrams as if each might be instructive, how these communications intended for personal viewing managed to find themselves circulated for exhibition and sold for profit by their recipients and dealers alike. In his walking tour of the exhibition, The Power Plant director Gregory Burke noted that Kawara doesn’t see the profit. While it seems plain that Kawara’s telegrams were made as art, they feel more like love letters. And love letters by famous people don’t become objects of commerce until usually posthumous biographies are written (consider Hannah Arendt’s self-described “banal” exchanges between herself and Martin Heidegger, for example).

In the third and most elegantly used space within the exhibition rest 20 books, ten in each of two vitrines. The leather-bound books contain the printed sequence of years counted backwards from 1969—One Million Years (Past) dedicated to “all those who have lived and died”—and forwards from 1980—One Million Years (Future) dedicated “to the last one.” The packaging and containment of all those years in numbers, books and vitrines is a bit of a mind-trick, but the companion series of readings from the books (on Sundays) offers some perspective. If read straight through, it could take decades. Reading numbers aloud from the books. I wonder, if Kawara had created the project with the readings in mind, would he have chosen seconds instead of years? Performers reading the seconds in real time (living in the moment). Perfection. (A 73-minute excerpt from one of the readings can be found at http://www.ubu.com/sound/ kawara.html.)

What compels an artist to devise a set of generally daily tasks to be repeated for most of his life? Never mind the fact that this is what people do—feed ourselves, wash the dishes, get to work on time, care for ourselves and those around us. How is it different when an artist rejects the so-embraced luxury of exploration, experimentation and creation of the “new” in favour of systems, structures, habits and routines?

On Kawara, I Am Still Alive, various dates, 1970–2000, telegrams, dimensions variable. Photos: Raphael Goldchain.

Kawara’s work is about time: being aware of it, making use of it, making it apparent to himself and to those who view his works. There is also something about this work that has to do with boredom—where boredom has less to do with an absence of engagement than with the very notion of potential—of imminence. Boredom here has positive connotations. Could it be that artists make art (grapple with the meaning of existence—in time) because they are bored and because they are turned on by possibility? (My informal survey confirmed that artists either make art to avoid boredom, or to achieve it—but artists are famous for their quips.) Lars Svendson, in his wonderful little book A Philosophy of Boredom, claims that boredom “is usually a blank label applied to everything that fails to grasp one’s interest” and that “boredom involves a loss of meaning, and a loss of meaning is serious for the afflicted person.” Life is boring. It is routine. The days go by, the months, the years. They pass and we’re left with evidence of time’s having been. When there is nothing but to pass the time, doing it so self-reflexively as Kawara does isn’t devoid of meaning: it is meaning.

While Kawara has created an art practice that is pure self-representation, what he does so wonderfully (and with incongruous brevity) through his work is to raise the questions about being that are so difficult to articulate in words without sounding soft and wishy-washy (unless we speak again of Heidegger, for example). What does it mean to be alive? Is there a purpose? Does anything we do matter? To what end? Why? Perhaps it takes a moment to grasp the scope of his efforts because Kawara’s works are so simple in their conception and design. Kawara brilliantly bides his time—his life, even—through his art. He makes real the notion of living for art. ■

On Kawara’s “Consciousness. Meditation. Watcher on the Hills” exhibited at The Power Plant in Toronto from December 9, 2005, to March 5, 2006.

Risa Horowitz is an artist and writer living in Toronto.